Contents

For most students of Latin, learning Latin means sooner or later reading classical Latin literature. However, understanding this literature, written by and for a highly educated elite in a foreign cultural and historical context, can be quite challenging, even more so when written in a language without native speakers.

Suggested reading: Can Latin be spoken today?

It is, of course, best to first learn Latin well by studying level-appropriate textbooks instead of literature, but if you are a student, you might not have the choice. I’ve spent over a decade learning and teaching Latin, and, over the years, I’ve collected several tips and techniques for facilitating reading classical works. Today, I’ll share some of them with you.

Let’s begin.

Know Latin

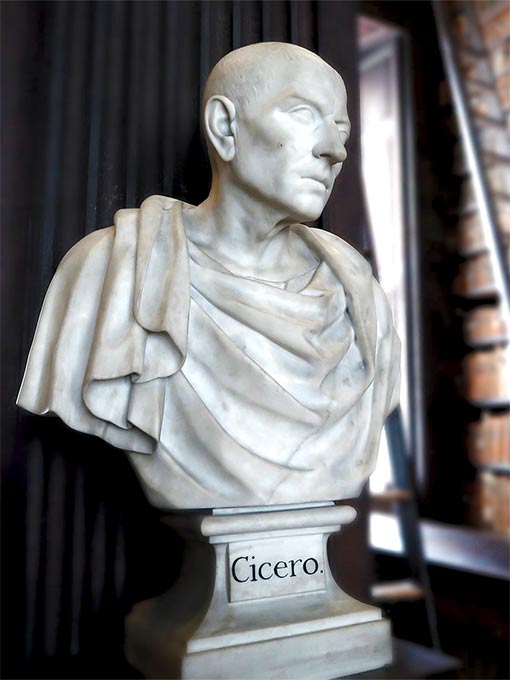

This might seem strange but in order to read Cicero, you have to know Latin very, very well. So, if you can, defer reading Cicero and other literary works, read easy texts, read a lot, build your vocabulary and intuitive understanding of Latin.

Suggested reading: Reading Plan for Learning Latin: Beginners

Now, if you have to read Cicero right now because you have a burning desire or because your teacher tells you to, here are some suggestions.

Note! Some of these suggestions might seem to require more effort and time than you want to spend. They range from easy-to-do suggestions, to quite diligent and conscientious work. Use the ones you think will be suitable for you. But don’t be too easy on yourself :).

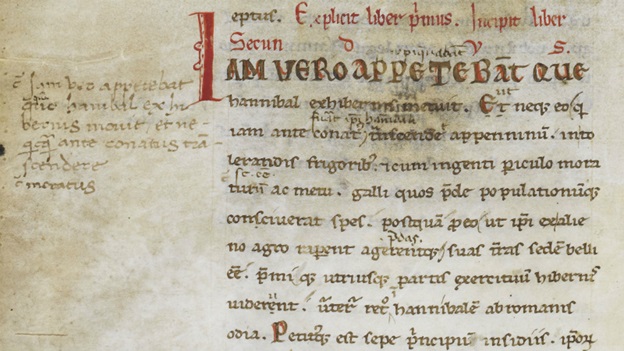

Get a Good Commentary

Reading a classical author is no easy task, even if you understand every single word and construction of every single line. There is so much context, so many things that every reader in antiquity had. In every single speech of Cicero or the Sallust’s historical works, there are so many references to laws, government officials which everyone at the time understood. Furthermore, the nuances of word order and register and subtle intertextual or historical references would have been apparent to educated native speakers of the time.

We don’t have that conceptual framework and contextual understanding.

However, all hope is not lost.

Over the centuries, through (too?) diligent philological work, scholars have been able to reconstruct much of that framework and the necessary historical, cultural and linguistic context necessary to better understand literary works of ancient Rome.

Therefore, if you are reading a classical author, you should be using a commentary or several which will explain grammar, words, and cultural and historical aspects of the text.

I suggest you get a modern commentary and one written in Latin. The first will give you the latest research on the text, whereas the other will do much of the same thing but allow you to practice and expand your Latin.

Thus you will hit two flies with one stone–or catch two wildbores in a forest-pasture, as the Romans said (duos apros in uno saltu capere).

Where do you find these Latin commentaries?

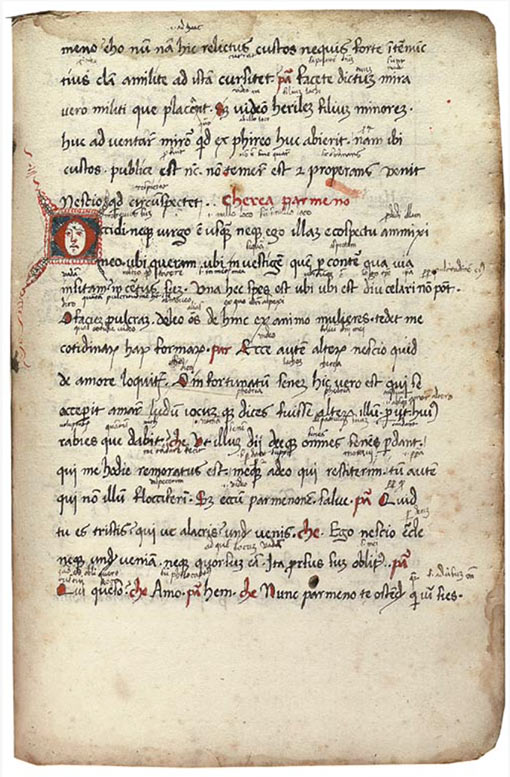

You can find modern commentaries for most of the famous classical texts on Amazon; I suggest you get a two, as they tend to explain different words and constructions. For Latin commentaries, there are ones on classical texts dating back to antiquity (e.g. Donatus for Terence and Servius for Vergil), but here I have two sets of later commentaries in mind:

- Bibliotheca Classica

- Ad Usum Delphini

Both Bibliotheca classica and Ad Usum Delphini are available as free PDFs.

They each have their strengths and weaknesses, and it would be best to use a commentated edition of a text of Cicero from both series. These commentaries vary in detail but generally explain difficult words and historical references quite well, in a rather straightforward style of Latin.

This brings me to the next point, which is similar, only different in scope and generality.

Read About the Historical Context

It is much easier to understand an oration of Cicero if you understand the historical context. If you know what led up to the speech, what its point was. Cicero’s speeches are like a scene from a movie, but it is tough to understand what is happening in that particular scene without watching the rest of the movie.

So, if, for instance, you are to read the first oration against Catiline, make sure you read about the Catilinarian Conspiracy, what prompted it and what the consequences of it were. Understand what was happening in Rome, what the different political parties, their ambitions, and goals were. Similarly, if you are to read Ovid’s Metamorphoses, you will have to read up on Greek mythology as virtually every page is replete with references to gods and heroes.

Get a Few Translations

Now, using translations, someone might say, is cheating, it means that you don’t know the language.

This is false.

If you’re reading Virgil (and haven’t studied the text before) and look up no words, well perhaps you don’t need a translation, congratulations, you are part of a very select club that silently rules the world. 🙂

But most students who read Virgil will find the text of the Aeneid, for instance, quite difficult (even though it is a pleasure to read). If this is the case, you will learn much more Latin and get more pleasure if you can get through more than a page per hour.

A translation will help you with that.

You can use a translation in many different ways: you can read it only when in doubt, read one line from the translation and then one in Latin, or vice versa, or read paragraph by paragraph comparing the Latin with the translation.

There is no wrong way, and there is no right way. There is only the way that gets you through as many texts as possible with understanding and pleasure.

One caveat: Do not become too dependent on the translation. Instead, use them when you truly need to. Seek to develop confidence in your own ability and judgment.

There are two main types of translations you can use, traditional parallel translations and interlinear translations. In texts with parallel translations, you have the Latin text on the left hand and the translation of the same page on the right hand. A great example of this is the Loeb series.

Interlinear translations, on the other hand, give you the English equivalent under each word of Latin. The drawback of these is that they are rare, and you cannot avoid looking at the translation since it is just below the Latin text.

I recommend parallel translations to my students.

Get a reading partner

Studying Latin can often be a very solitary project—even if you are taking a course at university—since students have to do most of the work of understanding the texts outside of the classroom. When I took Latin at college many years ago, we’d all prepare the text for class at home and then in class go through it with the teacher. Then everyone would mostly go home and study by themselves.

If you’re learning Latin as an autodidact, solitary study is almost a given–and for some an allure of Latin.

However, working through complex literary texts, such as Cicero’s orations, takes much work if you are not advanced. Having a study buddy to discuss difficulties, interesting expressions, or references makes learning Latin much more pleasant.

So, I would suggest that you find someone, either in school or online, and decide on what you are going to read. Then discuss it together over a cup of coffee or a beer. I’ve spent many nights with friends in a Latin circle discussing Horace, Erasmus, and other authors.

Furthermore, we all bring different experiences and perspectives to a text, and sharing others’ interpretations of the text can enrich our understanding and appreciation of it.

Make Notes in the Book

In the classic guide to reading, How to read a book, by Mortimer Adler, the author tells the reader to read with a pencil and to make notes in the book, circling interesting or difficult passages, writing questions or summaries of arguments in the margins, and in essence, entering into dialogue with the author of the book.

At first, I was reluctant to write in my books, but I decided I’d give it a try–and indeed, reading in this active manner made the reading not only more engaging but much more fruitful. Of course, Adler talks about reading in a language that you already know, but reading with a pen in hand is a potent technique for learning a language. Indeed, Erasmus of Rotterdam, the great Dutch humanist and teacher, suggested we mark interesting, rare, or difficult words and expressions.

If you don’t want to write in your invaluable editio princeps from 1557, I understand, nor should you do that. Instead, go on Abebooks or eBay and get a cheap, used copy of the text you are reading. You can get most classical works for a few dollars.

Reading with a pen in this way prepares the way for the next powerful technique.

Keep a Commonplace Book

Erasmus–and virtually all his contemporaries–suggested learners copy out phrases and expressions, and indeed, whole passages that they found interesting. This way, you build up a personal dictionary of words and phrases that you can categorize according to your own inclinations, thematically or by author.

By keeping such a book, you’ll not only read very attentively and have a source of expressions for Latin prose composition, but you’ll also have a record of your reading through the years.

Use a Dictionary of Synonyms

We can learn a lot from using translations and commentaries, but when reading, we might come across several words translated with the same word in English.

Of course, there are differences in nuance and usage between the Latin “synonyms,” but how do you get at them?

Regular Latin dictionaries might help somewhat, but usually, they are limited to offering many possible translations of a particular word. Luckily, there are good dictionaries of Latin synonyms, which treat the differences between synonyms. You can find the best synonym dictionaries here.

Note, however, that there are no native speakers of Latin who can tell us about the exact nuances of each word, so philologists have had to work hard to determine the meaning from usage and comments on usage. You’ll notice that different dictionaries of synonyms make different distinctions between Latin synonyms. Like all Latin dictionaries, they are guides, not laws written in stone.

Decide on a Reading Plan

How much do you want, or have to read a day?

As we all know, learning a language takes time and patience. It is always better to spread out your learning so that you, for instance, read 20 minutes every day rather than 3 hours on Saturday.

So, decide how much you can do every day, e.g., read for 20 minutes or read two pages. Try making it a daily habit by doing it at the same time and in the same place every day. Also, try to facilitate performing the habit by putting your books next to where you are going to be reading. Thus, all you have to do is sit down and start reading. Furthermore, the books lying on a table next to a chair will act as a reminder.

If you are like me and enjoy checking things off lists, you could place a calendar on the wall and make a cross over each day you’ve kept your habit. That sounds like turning reading into a chore, dixerit quispiam (“someone might say”), but I found it actually adds a level of pleasure and sense of accomplishment to the reading session. Also, the calendar works as a secondary reminder.

Suggested reading: How to Learn Latin: Motivation, Goals, and Habits

Re-read

We now come to the final, but perhaps most important tip: re-reading the text. As you know by now, reading and understanding a literary text from antiquity, be it prose or poetry, is much more difficult than it might seem at first: Beyond the language barrier, there is a sort of veil woven of historical context, references, and intertextuality that keeps us from fully perceiving the literary works as the Romans did.

This is where re-reading comes in.

You have worked through the text, understood the historical context, the references, and perhaps even the intertextual allusions. It’s perhaps been a long road.

First, well done! Few take the time to read Latin literature in this way. But it can be enormously rewarding, rather than just blazing through a book to say that you have “read it.”

Reading Latin is not a sport, it’s about literature and what we can learn and enjoy from it.

Now that you have pierced that veil and come close to the text, it would be a shame to set the book aside. Now, you have rendered the text or passage of text fully comprehensible to you. Reading it a second time will be much easier, and you will be able to understand the nuances much better and thus get much more from the text.

So, how should you reread the text? There are two principal ways to do this. I suggest you do both. First, before starting a new study session, read the previous day’s passage or pages, consulting your notes and translation if necessary. After you’ve gone through the text in this manner and thus re-read every part, it’s time to read through the whole text from start to finish–preferably in one glorious sitting. I would suggest re-reading the book until you can read it with ease. Here is a guide on how you can truly master the contents of a Latin text.

Bonus Tip

After you’ve finished reading and rereading your text or passages of text, take your notebook, and write down your thoughts on the work. What are your impressions? Do you find it stands the test of time? Is it overrated? Was it difficult?

If you do this, you’ll have a personal record of your thoughts and your reading experience. And later, if you want to re-read that particular work, you can do the same thing and see if your thoughts and views on the work have changed over the years.

Good luck, and let me know how it goes!