Guest article written by Tom Keeline, assistant professor of Classics at Washington University, St. Louis.

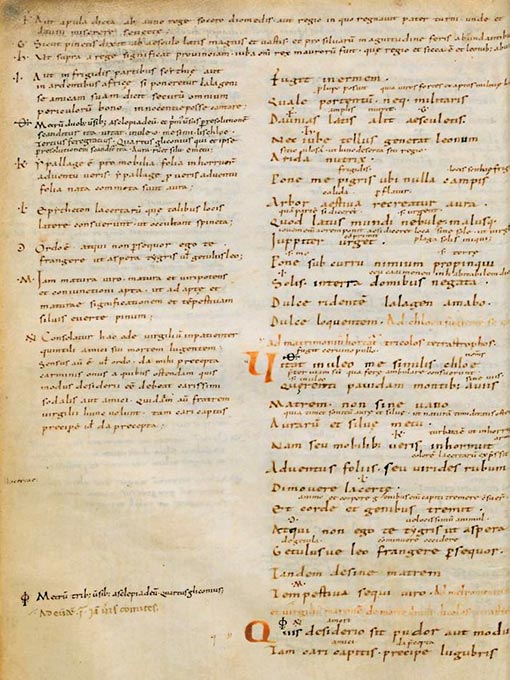

Vitas inuleo me similis, Chloe,

quaerenti pauidam montibus auiis

matrem non sine uano

aurarum et siluae metu.

I bet you can’t understand that Latin sentence the first time you read it. I bet you can’t even understand it if you read it again—go ahead, give it a shot. Maybe you can, of course, and if so you’re better than I am, since I got stuck on it one day last month. I was sitting in the park one Saturday during a rare reprieve from a cold and snowy January, keeping half an eye on my children while preparing for one of my classes on Monday. We’d be covering book one of Horace’s Odes in my graduate survey that day, and so I had 38 poems to read. (We move pretty fast: as a colleague of mine jokes, “if it’s Tuesday, this must be Tibullus!”) The last time I’d read this particular poem—Odes1.23—was, as near as I can tell, about seven years ago, and in that time I’d forgotten the key word that unlocks much of the mystery of that first stanza: inuleo. If you could read the stanza at a glance with ease and pleasure, then you knew that word, and I’d make a further bet: it’s probably because you already have read this poem, and you managed to remember it better than I could.

Here’s a bit of help for those who haven’t read it or whose memories are as porous as mine: inuleus means “fawn.” Does that help? Here’s a bit more background: in this stanza Horace compares his love interest, Chloe, to a skittish young deer who runs off to look for its mother in the mountains, naively fearing the sights and sounds of nature. Maybe you can follow it now. It goes something like, “you avoid me like a fawn, Chloe, a fawn who seeks its frightened mother in the lonely mountains out of a foolish fear of the breeze and the trees.”

If you don’t know the word inuleus, you will almost certainly be stuck. It’s just one word, but if you don’t know it, you probably also can’t tell whether uitas is the second-person singular verb “you avoid” or the accusative plural noun “lives,” because inuleo might equally be an unrecognizable noun—nominative? dative? ablative?—or an unrecognizable first-person singular verb. similis won’t help: nominative singular or accusative plural? By the time you get to the second line, you’re probably just lost—there are too many uncertainties to try to hold onto in your working memory.

Now of course you can eventually sort this out. I didn’t bring a dictionary with me to the park, but when I flipped to the commentary in the back of Roland Mayer’s Cambridge Green and Yellow—I wasn’t bringing Nisbet and Hubbard to the playground!—I found the word glossed as “fawn.” I then remembered Anacreon’s similar poem, which only came back to me because Anacreon memorably wrote that female deer have antlers (Anacreon fr. 408, generating a fierce zoological controversy in antiquity; Aristotle was indulgent). Suddenly Horace’s whole stanza fell into place, flowing smoothly through the mental channels that I’d carved out the last time I’d read the poem in the fall of 2011.

But “you can eventually sort this out” is not the point. Or perhaps it is a corollary of the point. The point is that, if we believe the SLA research, you need to know 95–98% of the words in a given passage in order to read it. By “read,” these researchers typically mean move your eyes once over the sentence and more or less instantly take in its meaning. They certainly do not mean “look at a sentence in puzzlement, consult a dictionary and/or commentary and/or translation, and eventually extract its meaning.”

But knowing 95–98% of the words in a given passage? That’s an almost impossibly high bar for most Latinists to clear when they’re reading many, if not most, ancient Roman authors. The same SLA researchers who point out the “95–98% rule” will often argue that vocabulary is best learned through comprehensible input and extensive reading (more here). If you could only read enough passages where you know 98% of the words and the unknown inuleus occurs too, you’d eventually learn how to say “fawn” in Latin. Researchers are not agreed about how often you might need to be exposed to a word in order to learn it, nor are they easily able to take into account the fact that some of us forget words that we knew perfectly well seven years ago, but you pretty clearly need to do a whole lot of reading. Many proponents of extensive reading want students to be reading a book a week at the beginning and intermediate levels; two or three a week at the advanced level, and we are not even remotely close to having that many high-quality compelling and comprehensible Latin texts (seen in these terms, the current profusion of Latin novellas is only a tiny drop in a very large bucket).

But let’s just leave those issues aside for the moment, because there’s almost no way that you’ll ever learn inuleus through extensive reading. Indeed, the only other passage in Latin literature where a typical Latinist is likely to see the word is Propertius 3.13.35. Aside from that, it makes a handful of appearances in Pliny the Elder (and his epitomator Solinus), as well as a series of cameos in Scribonius Largus. If your reading extends to the mid-fifth century, you might also come across inuleus used once in Eucherius’s Formulae spiritalis intellegentiae (for those keeping score at home: form.4 p. 26 ll. 11–13 in Karl Wotke’s edition). But you could, simply put, read through all of extant ancient Latin literature and still not have come across this word enough times to have internalized it in your mental representation of the language. (And you probably wouldn’t be able to “read” many of those other passages either, even if you did look at them, since you aren’t likely to know 95–98% of the words in the surrounding context.) And most classicists will never see the word outside its single occurrences in Horace and Propertius.

Horace is about as canonical as they come, but I’m going to wager that anyone who can “read” Horace (in the SLA research sense) has already “read” Horace (in the classicist, hack your way through this with a mental machete sense). I admit that to conduct rigorous research on this claim would be both impractical and almost a form of student abuse: we would have to train up a crop of Latinists to become as proficient as possible, all the while systematically denying them the pleasures of Horace, just so that we could one day test whether they could actually read and understand him at sight. But even if we were to perform this cruel experiment, I’m fairly confident they wouldn’t succeed.

Is the example of inuleus cherry-picked? Maybe. It’s what stopped me in my tracks the other day, and that’s why I picked it. But open up your own Horace to a poem you haven’t read in a while (or have never read), and see how you do. This one, for example, continues:

nam seu mobilibus uepris inhorruit

ad uentum foliis seu uirides rubum

dimouere lacertae,

et corde et genibus tremit.

There are serious textual issues here, but ignore those for our present purposes: uepris, rubum, lacertae—do you know them all? (I was two for three on Saturday in the park, having forgotten rubus “bramble bush,” and the commentary didn’t gloss it for me. I couldn’t figure it out from context and had to look it up when I got home.)

Since I’ve quoted two-thirds of Horace’s poem, I might as well quote the last stanza as well:

atqui non ego te tigris ut aspera

Gaetulusue leo frangere persequor:

tandem desine matrem

tempestiua sequi uiro.

I managed to do a bit better with this one, but I never even could have made it to this stanza without help getting through the first two.

Now can we do pre-reading with our students to prepare them to read this poem? Of course we can, and of course we should! But in a larger sense, we really can’t prepare ourselves to read such poems (i.e., not “this poem” but poems like it). Active Latin and comprehensible input on their own simply will not get us there. The amount of pre-reading and preparation you’d have to do to read Horace’s four books of Odes at sight is so enormous as to be all but impossible: reading through all of extant Latin literature would be a good start, but it still wouldn’t get you all the way there. And that is just to speak of vocabulary and not even to get into issues of cultural literacy, word order, syntactical oddities, textual troubles, and so forth—separate articles all!

Someone might point out that you don’t have to limit your reading to classical Latin, and they might suggest that you read contemporary novellas and other Latin written by later authors. I agree! I think that reading Renaissance Latin in particular has done a lot for my abilities to read Roman authors. Much of later Latin won’t count as comprehensible input for most Latin learners, but it offers an almost immeasurably greater variety of topics and levels than ancient Latin alone. Such texts still aren’t likely to teach you inuleus, but they will help reinforce a lot of other vocabulary. And some medieval and Renaissance texts really do count as level-appropriate, compelling, comprehensible input; some of this Latin really can be “read” in the SLA sense of the term. Such has been my experience, at any rate.

Nevertheless, reading later Latin has its own dangers: later authors were not native speakers of Latin, and they perforce lacked the Sprachgefühl needed to wield the language with native-speaker proficiency. We cannot necessarily trust their intuitions about word order, or distinctions between approximate synonyms, or any of a number of other relatively subtle points.There is, simply put, a danger that we may develop an inaccurate mental representation of the language. (And this is to say nothing of new associations with old words: if you speak Latin or read post-classical texts, what pops into your head when you see raeda or prelum?) I think in practice the benefits far outweigh the risks, but I’d suggest that you read later Latin for its own sake—and it is absolutely worthy to be read!—not just for its potential to help you read Caesar and Vergil. That’s just a side benefit.

Active Latin and comprehensible input alone are not going to make people perfect readers of ancient Latin literature, at least not for any future I can realistically imagine. For many—I suspect most—ancient Latin texts, there will remain some gap between our level of reading proficiency and the level that the text demands in order to be read fluently. That gap can be bridged by teachers and commentaries and dictionaries and perhaps by explicit knowledge about grammar and how the Latin language works, and we can in the end get meaning from these texts, and enjoy them, and eventually re-read them in the way that they were meant to be read. But on a first reading, that gap will be there for most of us most of the time.

What Active Latin can do, I suggest, is narrow that gap. Readers who never do anything but translate will have a much larger gap to bridge, and their journey is much longer and harder. On the other hand, readers who have worked to develop a sophisticated and accurate mental representation of the language through comprehensible input, wide reading, extensive listening, and so forth will still need to traverse a bridge from where they are to where the ancient Roman authors stand, but their journey is shorter and easier. Downhill rather than uphill, to change the metaphor a bit. They will have to look up a handful of words, but not every other word. They will have to consult commentaries, but when they do so, they will also get profit and pleasure from the consultation, not just an English crib of the Latin. They’ll even need to read translations sometimes, and that’s ok, because they won’t be solely reliant on them for their understanding of the Latin.

You wouldn’t try to read Dante today without first learning modern Italian, or Shakespeare without first learning contemporary English. Latin literature is our equivalent of Dante and Shakespeare, and Active Latin is the closest thing we’ve got to “learning Italian” or “learning English.” But the ancient Latin texts that we read are not, by and large, “level appropriate”; we’ve got nothing except the ancient equivalents of Dante and Shakespeare. We’ve got texts that were written at the highest level of sophistication for an elite audience of supremely well-educated contemporary native speakers. They weren’t written for us. Do I think these texts are eminently worth reading? Of course—I’m a classicist! But we shouldn’t delude ourselves or our students: the gap between us and those ancient native speakers is never going to be fully bridgeable by waving any magic wand, whether it’s labeled “Active Latin” or anything else.

If the final destination of this journey is to “read” ancient Latin the way we read our native language, we may never get there. I’m certainly nowhere close. Should we just give up then? Well, I don’t think so. As with geometry, there is no royal road to Latin, but I think I’ve made a lot more progress by embracing Active Latin than I would have otherwise. I’ve definitely had a lot more fun. If reading ancient Latin the way I read English remains an elusive goal for me, getting meaning from Latin texts with ever-increasing ease and pleasure is a completely reasonable goal that I make progress towards every day—well, let’s say “most days”! If we begin with such a goal in mind, then we can constantly strive for a perhaps unattainable perfection while still enjoying every step of the journey. And this, I think, is the realistic promise of Active Latin.