Contents

On January 10th, 49 B.C., Gaius Julius Caesar uttered one of history’s most famous lines, Iacta alea est (sometimes written alea iacta est), after which he crossed the Rubicon river with his army and set the Roman Civil War in motion.

A Well-Known War

Thousands of pages have been written about Julius Caesar, Pompey and the Civil War fought between them. Movies have been made, books have been written, TV-series produced,so we shall not dwell too long on the issues of war.

However, in order to get a good grasp of the meaning of Caesar’s enormously famous expression, let me just give you a short recap of the story.

Caesar’s Command

In the 50’s B.C. there were some political tensions between Caesar and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey, a man he had previously been in an alliance with.

The alliance between Caesar, Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus had been an informal coalition, know to history as the First Triumvirate. Crassus, however, fell in the battle of Carrhae in the Parthian war.

Suggested reading: Omnia Vincit Amor: Love in Ancient Rome

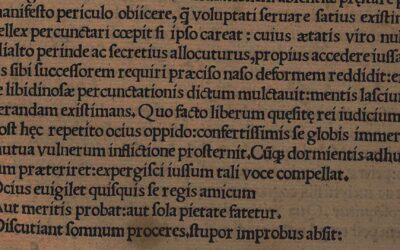

At the time of his famous quote, Caesar had for 9 years successfully been campaigning in his provinces north of Italy – Cisalpine Gaul, Transalpine Gaul and Illyricum – gaining quite a lot of popularity.

For quite some time, he had moved within a rather grey area, legally speaking; by 51 B.C. the Senate wished to replace him as governor of Gaul and decided that his army should be disbanded by November 13, 50 B.C. (Rondholz, p. 433)

Caesar proposed that he would lay down his command over Gaul if Pompey gave up the command he held over Spain. This was ignored. (Boardman, Griffin & Murray, p. 94–97; Boatwright, Gargola & Talbert, p. 145–157; Jones & Sidwell, p. 42–43)

Caesar was declared an enemy of the state on January 7th 49 B.C. (Rondholz, p. 433)

Leading A Legion

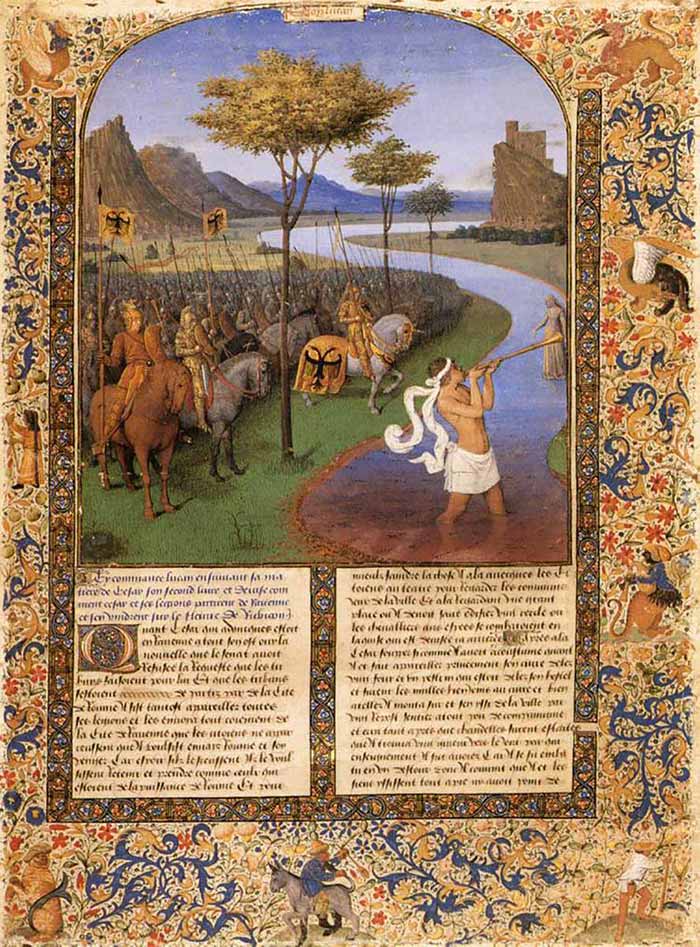

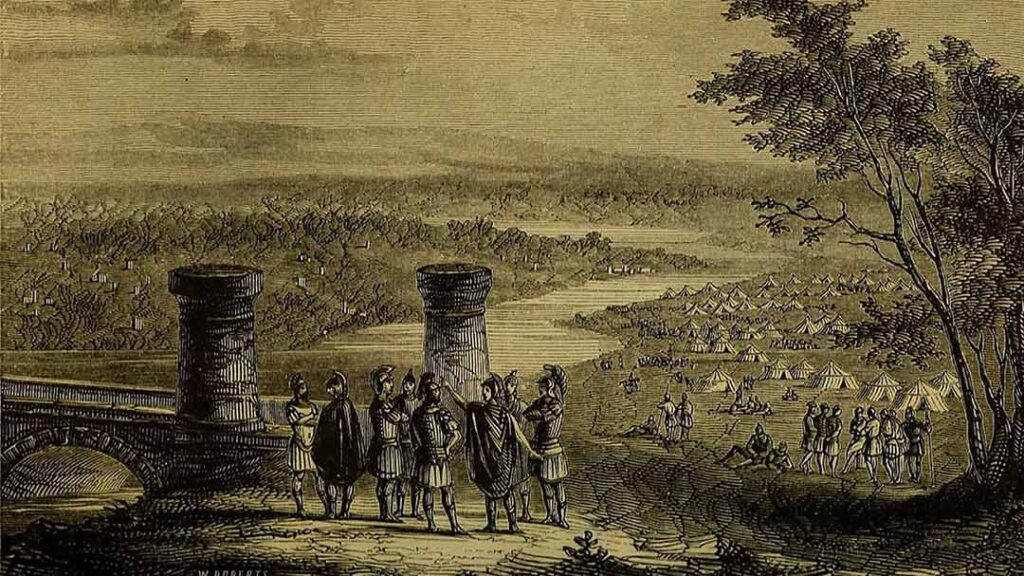

On January 10, 49 B.C. Gaius Julius Caesar led Legio XIII, the thirteenth legion, from Ravenna in northern Italy over the river Rubicon towards Arminium (modern Rimini) and on towards Rome.

The Civil War was a fact.

But why was this move so important?

The political environment had for a long time been infected and war was imminent, so how come crossing over a small, rather insignificant river was to become the symbol for the end of the Republic?

Treason

As governor Caesar held the right to command troops within his own provinces, i.e. Gaul, but not within Italy. Italy answered to Rome and Rome alone.

This meant that Caesar, by law, was forbidden to command an army in Italy.

The river Rubicon has never been a large river. It wasn’t a hard river to cross. There were no casualties from trying to fight hard currents or anything like that. Instead, the Rubicon was a border.

The Rubicon marked the border between Caesar’s province, Cisalpine Gaul to the north-east, and Italy itself. Crossing the river meant crossing the border into Italy.

Crossing the border still in command of your troops, meant breaking the law.

It meant treason.

It meant war.

Not only did Caesar himself break the law as the governor and commander, but his army broke the law by following a man who had no authority of command.

The Cry And Cast Of Caesar

There are several Roman sources that inform us about this event, but our Latin quote, the memorable Iacta alea est, comes from the historian Suetonius’ biography De Vita Caesarum: Divus Iulius.

According to Suetonius, after some hesitation at the river, Caesar was given a sign by the gods as an apparition, playing a reed pipe, snatched a trumpet from a by-standing soldier and sounded a battle signal. Caesar then cried out:

“‘Eatur,’ inquit, ‘quo deorum ostenta et inimicorum inquitas vocat. Iacta alea est.’ ”

— Suetonius, De vita Caesarum, lib I, xxxiii.e. “Take we the course which the signs of the gods and the false dealing of our foes point out. The die is cast.” (transl. Rolfe, 1914)

The Die Is Cast

Traditionally Iacta alea est has been translated into “the die is cast” and used as a way of indicating that something has passed a point of no return, or that you have made your move and that things are now out of your hands and there is no turning back.

Some 300 years after Caesar’s exclamation we find a version of the phrase with Ammianus Marcellinus (330–400 A.D.): “aleam periculorum omnium iecit abrupte” (Amm., XXVI, xii) i.e. “hazarded at one cast all perils” that illustrates this perfectly.

However, it can be argued that other translations would suit better.

Game Or Die

As Caesar uttered these words the point of no return had not yet been reached, he had not yet made his move, because he said Iacta alea est BEFORE he crossed the river, not afterward.

To be fair, the decision had been made.

However, the word alea does not just mean “die” (i.e. the numbered cube used in gaming), it is also the game of dice itself or, more broadly, a game of hazard/chance.

A die was called tessera or talus in Latin depending on the amount of numbered sides.

A tessera had six sides, like our normal die, and the talus had four marked sides and two rounded unmarked.

We find a good example in Plautus:

“talos poscit sibi in manum,

provocat me in aleam”

— Plautus, Cur. 354–355i.e. “he asked for dice and challenged me to play a game.”

According to Isidore of Seville (560–636) –who wrote an etymological encyclopedia on everything– alea is a boardgame with dice, invented during the Trojan war by a soldier named Alea – hence the name. To be taken with more than a grain of salt, to be sure.

”Alea, id est lusus tabulae, inventa a Graecis in otio Troiani belli a quodam milite Alea nomine, a quo et ars nomen accepit. Tabula luditur pyrgo, calculis tesserisque.” – Orig. XVIII, lx

But there are also a few examples where alea is used to describe the die, not the game.

Game On

Perhaps sticking to the traditional use and translation of the proverb ”the die is cast” is the way to go. Where an irrevocable choice or decision has been made and the point of no return has been passed.

Perhaps another good translation would be something along the lines of “Game on!”, “The game is afoot.” or ”Let the game be ventured!”, as Lewis and Short propose in addition to the more traditional translation.

Maybe that was what ran through the mind of Caesar just before he stepped into the river – “Game on, Pompey, game on.”

We will never know.

What do you think?

Did He Actually Say It?

Now, I’ve been writing like Caesar actually uttered these famous words. But did he really?

We don’t know.

Maybe it is just an author’s wish to spice up the story of Caesar moving yet more troops from one place to another. Maybe not.

Caesar himself does not mention the expression it in his Bellum Civile. He does not even mention crossing the Rubicon.

Instead, he briefly states being in Ravenna, moves on to summarize his address to his soldiers and then swiftly mentions setting out with the thirteenth legion for Arminium. (Bel. Civ. 1.5–1.8). But nothing about the Rubicon, which is supposed to be somewhere in between these two towns.

What Say The Ancients?

Cicero, contemporary of Caesar, does not mention Rubicon or the cast of the die in his letters.

Neither does the historian Livy in his Ab Urbe Condita, written only 17 years or so after the event. (Tucker, p. 246) The relevant volume (liber 109), however, containing these events is missing. What we have left is the Periochae, i.e. summaries of the book itself. The summary does not mention the Rubicon or Iacta alea est, the book might have.

Another Roman historian, Marcus Velleius Paterculus (c. 19 B.C.- c. 31 A.D.), mentions Rubicon, but not the expression:

“…ratus bellandum Caesar cum exercitu Rubiconem transiit.”

— Velleius, 2.49

i.e. ”Caesar concluded that war was inevitable and crossed the Rubicon with his army.” (transl. Shipley, 1924)

The poet Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, or Lucan, has Caesar meet with a white-haired, sad-faced personification of Rome to ask Caesar not to go further. Instead of the famous Iacta alea est, Caesar says:

“Hic,” ait, “hic pacem temerataque iura relinquo;

Te, Fortuna, sequor. Procul hinc iam foedera sunto;

Credidimus satis his, utendum est iudice bello.”

(Lucan, Pharsalia, lib. I, 225–7)

i.e. “Here,” he cried, “here I leave peace behind me and legality which has been scorned already; henceforth I follow Fortune. Hereafter let me hear no more of agreements. In them I have put my trust long enough; now I must seek the arbitrament of war.” (transl. Duff, 1928)

And Suetonius, well he wasn’t even born at the time of the Civil war. He was born in 69 A.D. long after Caesar crossed the Rubicon and long after he had been murdered.

Local Latin Or Greek-Speaker

We have several more accounts about Caesar and his marching across the river Rubicon, these, however, are not in Latin as all the previous, but in Greek.

Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, or Plutarch, 46–120 AD, is the first one, to our knowledge, to have put the words Iacta alea est into the mouth of Caesar.

He wrote it in three different texts:

“ἀνερρίφθω κύβος”

— Plutarch, Moralia 206.7; Caes. 32; Pomp. 60

In one of them, Life of Pompey, he added that Caesar uttered the words in Greek, not in Latin.

Appianus Alexandrinus, or Appian, born even later than Plutarch in 95 A.D. was a Greek historian with Roman citizenship who wrote about the Civil War. He called Caesar’s famous exclamation, “ὁ κύβος ἀνερρίφθω.”, a familiar phrase. (Civil Wars 2.5.35)

Is Plutarch’s claim true? Did Caesar utter his famous words in Greek?

Again, we don’t know. It could be. The Roman elite was known for speaking Greek, like the Swedish or Russian nobility preferred to speak French in the 1700’s, so did the Roman nobility speak Greek.

But to be frank: we don’t know.

What we do know is that the quote Plutarch had Caesar say, predates both Plutarch, Suetonius and Caesar.

Proverb Of Playwrights

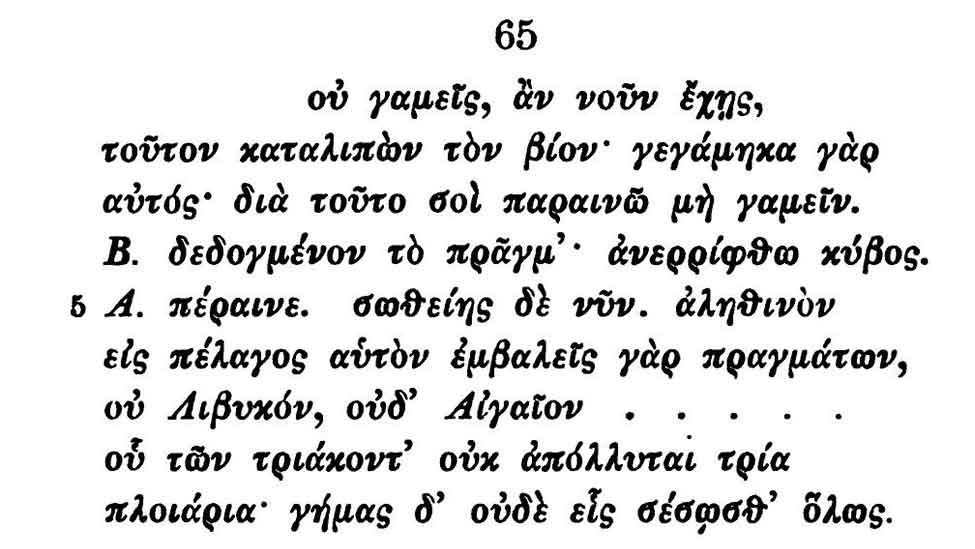

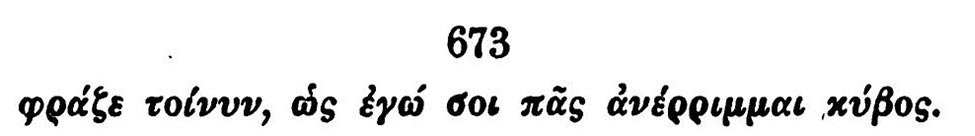

The expression is found in two fragments from ancient Greece.

One is a small fragment from the Greek playwright Menander (c. 341 – c. 290 B.C.):

The other is an older, even smaller fragment from none other than the famous playwright of ancient Athens, Aristophanes (c. 446 B.C. –c 386 B.C):

So, the proverb, or expression, that Plutarch, Suetonius and Appian put on the lips of Julius Caesar is most likely a very old one. And perhaps he uttered the words in Greek, perhaps in Latin, perhaps not at all.

Unfortunately, we do not have access to Livy’s book 109 of Ab Urbe Condita nor any of the other sources for our sources – i.e. a biography of Caesar written by Caesar’s friend Gaius Oppius and the history of the Roman soldier, politician and historian Asinius Pollio, also contemporary to Caesar. (Rondholz, p. 433) So the question remains unsolved.

The River Rubicon

The river Rubicon never had any importance as a river, only as a border. We know that it was situated somewhere between Ravenna and modern Rimini, but not exactly where.

This might seem odd but, when Octavian merged Cisalpine Gaul with Italy, the river lost its importance and its location was soon lost in the mists of history.

How can that be you ask? How can you lose the location of a river?

Well, as mentioned, the Rubicon has never been a large river – as rivers go, there are more important ones. Moreover, in the area where Rubicon is supposedly located, south of Ravenna and north of Rimini, there are several small, shallow rivers. Also, rivers tend to change their course over time.

A Dictator’s Decision

By the Renaissance interest in the river was growing amongst humanist but it wasn’t until the 1930’s, on the initiative of Benito Mussolini, that the Rubicon, or Rubicone in Italian, was officially identified as being the river Fiumicino.

In 1933 Mussolini ordered the name of the Fiumicino to be changed. It was.

From that day, the Fiumicino has largely been accepted to be the Rubicon, but not everyone has agreed.

The Right River

In August 2013, to decide on the true identity of the Rubicon, a mock-trial was held in the small Italian town of San Mauro Pascoli

Fighting for the price was the Fiumicino, defended by Giancarlo Mazzuca, writer and newspaper editor, the river Pisciatello or Urgón, as debated by local teacher and journalist Paolo Turroni, and the Uso as argued by archaeologist Cristina Ravara Montebelli.

When the votes had been counted, Mussolini’s Rubicon lost counting only 173 votes, the Uso received 215 and the Pisciatello or Urgón won with 269 votes. You can read more about the mock-trial here.

However, Mussolini’s Rubicon is still called Rubicon.

Pompey’s Passing

We don’t know if the river Mussolini called Rubicon is the real Rubicon or if it’s some other river. What we do know is what happened once Julius Caesar had crossed it and brought his legion into Italy:

War happened.

As word spread of Caesar and his army marching towards Rome, Pompey and the Senate fled. This might have seen rash, but they were blindsided.

Traditionally, war was waged during the summer. During wintertime, armies rested.

For Caesar to march the thirteenth legion into Italy in January was unprecedented and took Pompey by complete surprise. No one expected any developments for the winter. (Boatwright, Gargola & Talbert, p. 155)

With this declaration of war, Pompey and his associates saw only one option – flight.

And, long story short, Pompey was defeated and killed in Egypt and Caesar was elected dictator for life. The Roman Republic was dead.

References & Recommended Reading

Ammianus Marcellinus. History, Volume II: Books 20–26. Translated by J. C. Rolfe, Cambridge, MA, 1940.

Boardman, John, Jasper Griffin & Oswyn Murray, eds. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Roman World, Oxford 2001.

Boatwright, Mary T., Daniel J. Gargola & Richard J.A. Talbert, A Brief History of the Romans, Oxford 2006.

Caesar. Civil War. Edited and translated by Cynthia Damon. Cambridge, MA, 2016.

Cicero. Philippics 1–6. Edited and translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Revised by John T. Ramsey, Gesine Manuwald. Cambridge, MA, 2010.

Jones, Peter & Keith Sidwell, eds.,The World of Rome: An Introduction to Roman Culture, Cambridge, 1997.

Kock, Theodorus, Comicorum atticorum fragmenta, vol i, 1880.

Kock, Theodorus, Comicorum atticorum fragmenta, vol iii, 1888.

Lucan, The Civil War (Pharsalia). Translated by J. D. Duff,Cambridge, MA, 1928.

Plutarch. Moralia, Volume III: Sayings of Kings and Commanders. Sayings of Romans. Sayings of Spartans. The Ancient Customs of the Spartans. Sayings of Spartan Women. Bravery of Women. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt, Cambridge, MA, 1931.

Plutarch. Lives, Volume VII: Demosthenes and Cicero. Alexander and Caesar. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin, Cambridge, MA, 1919.

Plutarch. Lives, Volume V: Agesilaus and Pompey. Pelopidas and Marcellus. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin, Cambridge, MA, 1917.

Rondholz, Anke ”Crossing the Rubicon. A Historiographical Study” in Mnemosyne, Fourth Series, Vol. 62, Fasc. 3, 2009.

Suetonius. Lives of the Caesars, Volume I: Julius. Augustus. Tiberius. Gaius. Caligula. Translated by J. C. Rolfe, introduction by K. R. Bradley, Cambridge, MA, 1914.

Tucker, Robert A., ”What Actually Happened at the Rubicon?” in Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte Bd. 37, H. 2, 2nd Qtr., 1988.

Velleius Paterculus. Compendium of Roman History. Res Gestae Divi Augusti. Translated by Frederick W. Shipley, Cambridge, MA, 1924.