Contents

Omnia vincit amor is one of the most famous of all Latin expressions. It is also one of the most used ones still today, both in the original Latin, in translation and in its familiar “altered” version Amor vincit omnia.

We hear the phrase in wedding speeches, we see it tattooed on men and women all over the world. Every other author throughout history has used it, paraphrased it or translated it. It has been used as book titles, as mottoes, it has turned into songs and films, jewelry, postcards and fridge magnets.

Publius’ Pastoral Poem

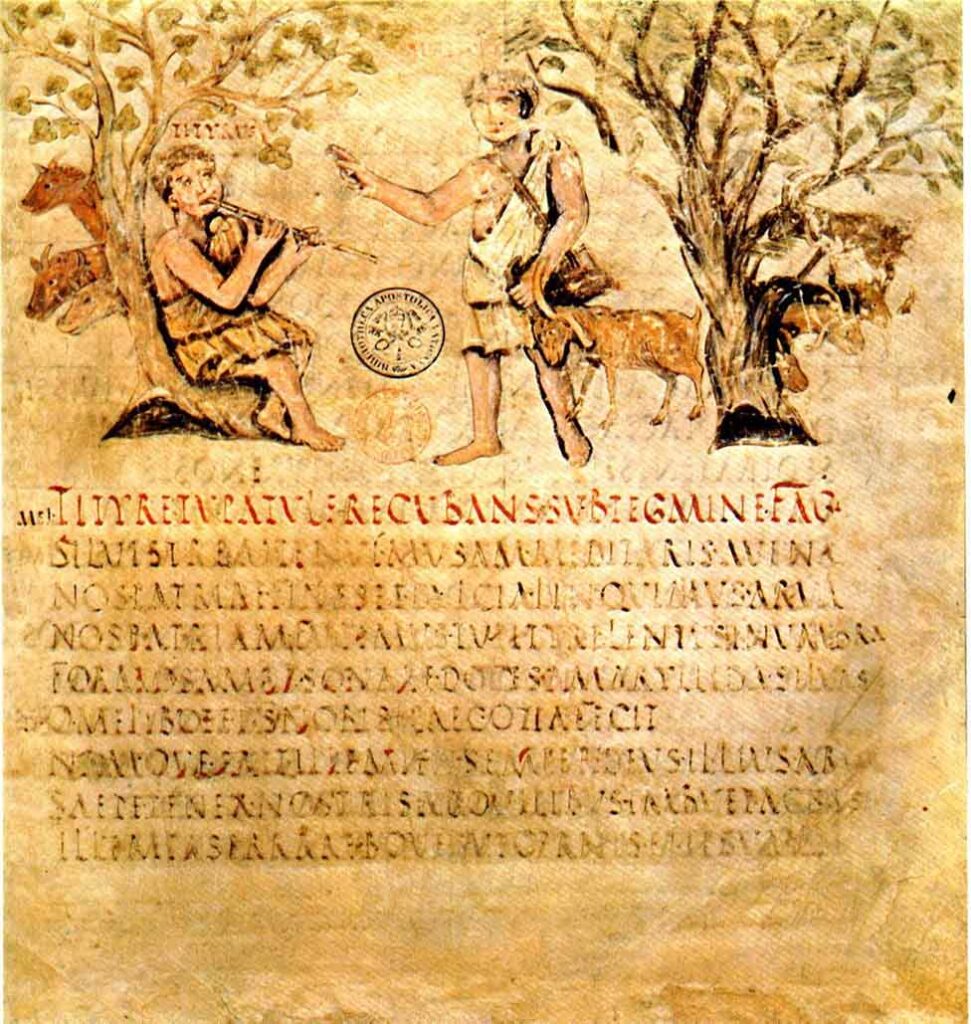

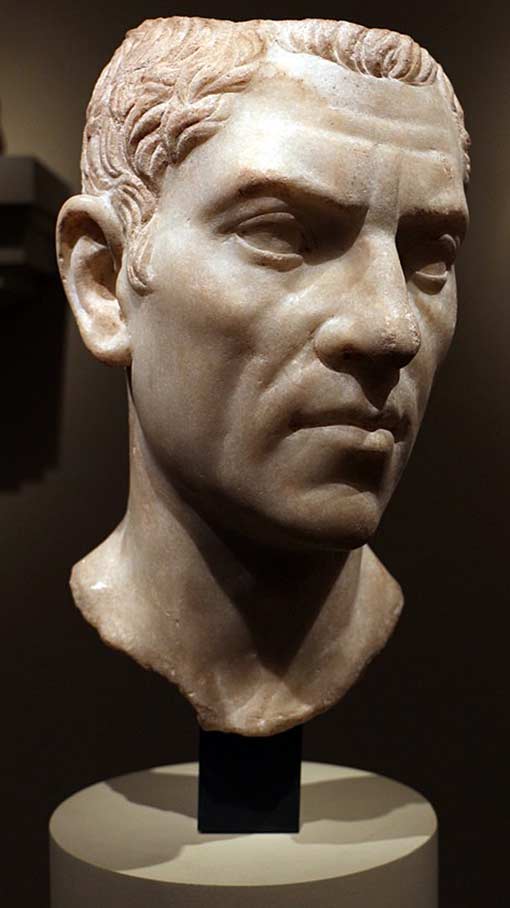

The expression Omnia vincit amor originally comes from the Roman poet Vergil, or Publius Vergilius Maro. Vergil was born the 15th of October 70 B.C in Andes, part of modern Pietole, near Mantua in Italy. He is most famous for his grand epos the Aenid.

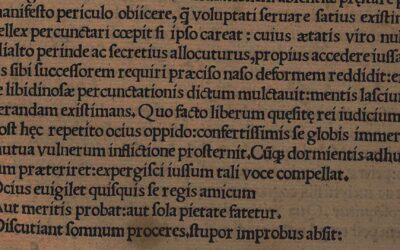

The phrase Omnia vincit amor, however springs from his first work, Bucolica or Eclogae.

Bucolica consists of ten pastoral poems published in 37 B.C. Omnia vincit amor is found in the last of those ten poems.

The full line in Vergil reads:

“Omnia vincit amor: et nos cedamus amori”

— Vergil, Ecl. 10.69

i.e. “Love conquers all; let us, too, yield to love!” (transl. Rushton Fairclough)

The expression needs very little explanation as to its meaning, it is self-explanatory being so clear within itself: “Love conquers/overcomes all.”

What needs to be said though is that it is not a proverb. It is an expression. A phrase uttered by a character in a poem. As time has passed, one could say that it has gained the weight of a proverb. But it is still just an expression.

Love for Lycoris

In Vergil’s poem, the words, Omnia vincit amor, are uttered by a love-sick man named Gallus as he is dying.

Gallus was so in love with a woman called Lycoris, that the god Apollo himself asked Gallus why he continued with the madness of love:

“Galle, quid insanis?”

Also, Lycoris had left with someone else.

To answer Apollo’s question: Yes, Gallus was mad. Mad with love.

Lycoris had left him and now he was dying in Arcadia from love and a broken heart. So great was his madness that not only did Apollo try to intervene, but so did the gods Silvanus and Pan. Neither of them succeeded.

Gallus’ Girl

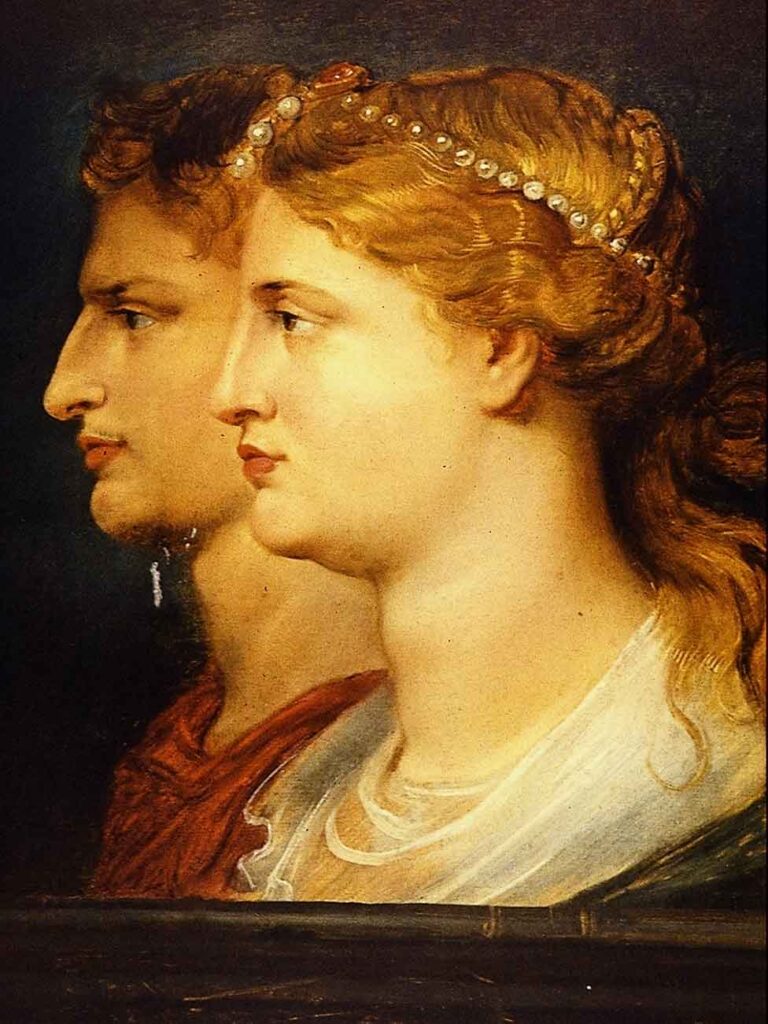

In the poem, Gallus is supposedly Gaius Cornelius Gallus (c. 70–26 B.C), a poet just like Vergil, taught by the same master as Vergil and a friend of the same.

The real Gallus wrote four books of elegies, now lost to us save for a few fragmented lines.

The elegies depicted his love for a woman whom he in his own and in Vergil’s works called Lycoris.

Lycoris was a poetical name for a famous actress named Cytheris, who was not only the love of Gallus, but the mistress of, amongst others, Mark Anthony and Brutus, though not at the same time. (Young Sellar, pp. 221–222)

Working the Vowels

Perhaps you are thinking to yourself :

”But isn’t it supposed to be AMOR vincit omnia?!”

Well, no. And yes.

A syllable in Latin is either short or long and as such certain words can only be placed at certain places in the various meters, which are like more or less flexible patterns of short and long syllables.

In the original words of Vergil, it is Omnia vincit amor and nothing else. Amor cannot stand first, as the poem is written in meter, hexameter, to be exact, and in order for the meter to work the first syllable must be long (omnia). The a in amor, however, is short.

In hexameter, the quantities of the phrase omnia vincit amor, work. But if you switch the words around to Amor vincit omnia – we no longer have a correct hexameter.

Caravaggio’s Creation

So is it incorrect to say Amor vincit omnia?

No. And yes.

It is incorrect if you want to be a purist and follow Vergil to the end of the world and use a right and proper quote.

It is correct if you just want to communicate that love conquers all, since the word order in Latin is very free.

But how has this altered word order become the standard of the quote?

Well, it has a lot (though not all) to do with the Italian painter Caravaggio who at the very beginning of the 1600’s made a painting of Amor, the Roman god of Love in the form of a Roman cupid.

This painting became very famous, and still is, and it was named ”Amor vincit omnia”.

Amor Above All

When we speak of love, or more importantly –tattoo it on our bodies– we want to make sure everyone understands that it is LOVE that conquers all.

So we put it first.

Because what if someone who does not understand the complexity of the Latin tongue sees the phrase Omnia vincit amor, and mistakingly translates it into ”Everything conquers love”?

That would be a disaster!

Romance in Rome

We know very little about love in Roman times. We have countless love poems, lines of affection, stories about political marriages, tales love-affairs and shameless sexual encounters.

Yet we know very little.

What we do know about love comes from the upper class and from marital laws and regulations.

We know that marriage was quite simple. No ceremonies were needed. You only needed to live together by consent as wife and husband, and you were married.

Divorce was the same.

Easy. You just split up. It was conventional to leave some explanation and reason for the separation, but nothing more. (Sidwell & Jones, p. 214)

Indecent Intimacy

We also have indications that public displays of affection was considered indecent.

Florence Dupont gives us a great example in Daily life in Ancient Rome, where she retells the story of Manilius:

Manilius was expelled from the senate by Cato the Censor as he had hugged his wife in broad daylight – in front of their daughter! (Dupont, p. 112–113)

Marriage was for the upper classes many times a business deal, as it has been throughout history. It was a political and financial arrangement.

Alliances between families were many times sealed with someone marrying into the other family.

Augustus, for instance, forced his stepson Tiberius to divorce his wife Vipsania Agrippina and marry Agrippa’s widow Julia for political reasons. Tiberius and Vipsania Agrippina cared too much for each other though, so Augustus had to make sure they did not meet again. (Jones & Sidwell, pp. 227–228)

Yet it was not always just a matter of business, there are numerous love poems and stories of affectionate couples.

Real Romance

Pompey Magnus was, for instance, infamous for being in love with all of his wives.

Pliny the Younger expressed deep love and longing for his wife Calpurnia in a most beautiful letter:

”Incredibile est quanto desiderio tui tenear. In causa amor primum, deinde quod non consuevimus abesse. Inde est quod magnam noctium partem in imagine tua vigil exigo; inde quod interdiu, quibus horis te visere solebam, ad diaetam tuam ipsi me, ut verissime dicitur, pedes ducunt; quod denique aeger et maestus ac similis excluso a vacuo limine recedo.” - Ep. 7.5

i.e. ”You cannot believe how much I miss you. I love you so much, and we are not used to separations. So I stay awake most of the night thinking of you, and by day I find my feet carrying me (a true word, carrying) to your room at the times I usually visited you; then finding it empty I depart, as sick and sorrowful as a lover locked out. ” (transl. Radice)

Cicero, while in exile, so longed for his wife and children that he was succumb by tears as he reads their letters:

“cum aut scribo ad vos aut vestras lego, conficior lacrimis sic ut ferre non possim.”

— Cicero, Ad Familiares 14.4

i.e. ”when I write to you at home or read your letters I am so overcome with tears that I cannot bear it.” (transl. Shackelton Bailey)

You can read and listen to the entire letter in Epistulae Ad Familiares XIV in the Latin Library / Latin learning app Legentibus. (3 day free trial)

He also called his wife mea vita, ”my life”, in the same letter and in another (Ad. Fam. 14.2) he calls her mea lux, meum desiderium – ”my light, my heart’s longing”.

And then of course we have one of history’s most famous love stories belonging to Mark Anthony and Cleopatra.

Their passion ending in tragedy as Anthony believed Cleopatra was dead and so stabbed himself with his sword. When he found out she was not, he was carried to her and died in her arms.

However, we don’t know how things looked for the lower classes.

If you want to know more about love, affection, marriage and sex in Rome, but not dive into this vast subject and drown (as it is easy to do), I would recommend reading the chapter about the Roman family in Peter Jones’ and Keith Sidwell’s The world of Rome: and introduction to Roman culture.

Love in Life & Litterature

Whatever we know and don’t know about love in Rome, from the sources one thing is quite clear: Love and Duty was at war.

Love vs. Duty is the underlying theme of many love stories. Duty to Rome, duty to the family, duty to destiny, duty to the gods…etc.

In real life we find such examples as that with Tiberius, Vipsania and Julia; or Marc Anthony being married to Octavian’s sister but having a passionate love for Cleopatra.

In Vergil’s Aeneid we find Aeneas struggling with his love for Dido and his duty towards his people, his old country deserving to be resurrected, his duty and loyalty towards the gods, his duty towards his old father and his son. He sacrificed his love.

The Roman ideal was a sort of hero, but without the happy sense of adventure and youthfulness. It was a heavier ideal, a serious hero. (Wistrand, p.60)

Vergil’s Veritas

Perhaps there was no war between love and duty at all, perhaps the relationship with love was simple, perhaps Vergil put the desire and belief of all of Rome into the mouth of Gallus as he defies gods and reason in Bucolica with his refusal of sanity declaring loudly:

“Omnia vincit amor”

– Love conquers all!

We will never know.

References & Recommended Reading

Cicero. Letters to Friends, Volume I: Letters 1–113. Edited and translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Cambridge M.A, 2001.

Dupont, Florence, Daily life in Ancient Rome, 1992.

Jones, Peter & Keith Sidwell, eds.,The World of Rome: An Introduction to Roman Culture, Cambridge, 1997.

Legentibus, Learn & Enjoy Latin – app for smartphones and tablets with a Library of Latin Read-Alongs and Audiobooks, including Cicero’s Epistulae ad Familiares and Letters from Pliny the Younger as mentioned in this article.

Pliny the Younger. Letters, Volume I: Books 1–7. Translated by Betty Radice. Cambridge M.A, 1969.

Plutarch. Lives, Volume IX: Demetrius and Antony. Pyrrhus and Gaius Marius. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge M.A, 1920.

Vergil. Eclogues. Georgics. Aeneid: Books 1–6. Translated by H. Rushton Fairclough. Revised by G. P. Goold. Cambridge M.A, 1916.

Wistrand, Erik, Politik och litteratur i Antikens Rom, Göteborg, 1978.

Young Sellar, William, The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Horace and the Elegiac Poets, Cambridge 2010.