Contents

Two thousand years of Latin Prose is a digital anthology of Latin Prose. Here you will be able to find texts from two millennia of gems in Latin. In this sixth chapter, we will learn more about one of history’s most famous men: Gaius Julius Caesar. We will also read a passage from his Commentarii de Bello Gallico(5.44) where Caesar speaks of two brave men – Lucius Vorenus and Titus Pullo.

If you want to learn more about the anthology, you will find the preface here.

Life & Works of Julius Caesar

(100–44 B.C)

Just like Cicero in the previous chapter of 2000 years of Latin Prose, Julius Caesar, needs very little, or no, introduction, as he is one of history’s most famous men. Here is a brief one anyway.

Life of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was born in 100 B.C. in Rome during the month of Quintilis which later became July, named after his family the Julii. During his life, he became a prominent military general, a politician, and in the end, a dictator. He was also a skilled orator and author.

We know a lot about Caesar’s life from his own accounts as well as from other contemporary sources, such as the letters and speeches of Cicero and the works of Sallust (86–35 B.C.). However, the biographies of Caesar written later by Suetonius (69–122 A.D.) and Plutarchos (46–120 A.D.) are also relevant sources.

Caesar was born in the city of Rome into a patrician family, i.e., the ruling class, the gens Julia. The Julii, according to Suetonius, descended from kings and the goddess Venus herself. (Div. Jul. 6).

About Caesar Being Called Caesar

The ancients had several ideas as to the origin of Gaius Julius’ cognomen, Caesar. Plinius Maior, or Pliny the Elder (23–79 A.D.), wrote that the name came from an ancestor who had been born by a surgical birth, an ancient Caesarean section. The name would, therefore, stem from the Latin word for “cut” (i.e. cutting out the child from the womb) which is caedo, cecidi, caedere, caesum (Nat. Hist. 7.5).

In Historia Augusta (probably from the end of 4th cent. A.D.) we find not just Plinius’ explanation of the origin of the name Caesar, but three more:

“Caesarem vel ab elephanto, qui lingua Maurorum ‘caesai’ dicitur, in proelio caeso, eum qui primus sic appellatus est doctissimi viri et eruditissimi putant dictum, vel quia mortua matre et ventre caeso sit natus, vel quod cum magnis crinibus sit utero parentis effusus, vel quod oculis caesiis et ultra humanum morem viguerit”

— Historia Augusta, Aelius 2

“Men of the greatest learning and scholarship aver that he who first received the name of Caesar was called by this name, either because he slew in battle an elephant, which in the Moorish tongue is called caesai, or because he was brought into the world after his mother’s death and by an incision in her abdomen, or because he had a thick head of hair when he came forth from his mother’s womb, or, finally, because he had bright grey eyes and was vigorous beyond the wont of human beings.” (transl. David Magie)

Now, Caesar issued coins with images of elephants, suggesting perhaps that he favoured the interpretation of his elephant-killing ancestor.

Or, perhaps he just liked elephants.

Caesar’s Career

As a young man, Caesar became the high priest of Jupiter, Flamen Dialis. He lost this title together with his inheritance when Sulla (138–78 B.C.) won the war against Caesar’s uncle by marriage, Gaius Marius (157–86 B.C.). Thanks to the influence of his mother’s family, things calmed down, and Caesar could pursue a military career. Caesar thus joined the army and left Rome.

After Sulla’s death, Caesar returned to Rome and became a lawyer. His career progressed, and he was soon elected military tribune, quaestor, and then aedile. In 63 B.C., he was elected Pontifex Maximus, i.e. high priest of the Roman state religion. Later, he became a praetor and was appointed governor of Hispania Ulterior.

Four years later, in 59 B.C., Caesar was elected consul alongside Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus (c.102–48 B.C.). However, Bibulus’ attempts to stand up to his fellow consul failed miserably. In reality, Caesar was acting as sole consul. Indeed, Suetonius reports that some people when signing documents jokingly dated them not as Bibulo et Caesare consulibus (“when Bibulus and Caesare were consuls”)—the names of consuls were used rather than years—but as Julio et Caesare consulibus (“Julius and Caesare were consuls”) (Suet. Caes. 20).

Around this time Caesar formed an informal alliance with Marcus Licinius Crassus (c.115/112–53 B.C.) and Pompeius Magnus, more commonly known as Pompey (106–48 B.C.). These men were later known as the First Triumvirate. Between the three, they had enough capital and influence to control public business and politics.

After his consulship, Caesar was set to govern Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum, with Transalpine Gaul added later. He spent nine years on military campaigns in these provinces and the lands that lay unconquered at their borders, and he did so successfully (from a Roman perspective). These campaigns are related in his Commentarii de bello Gallico.

After some initial years of success, the Triumvirate began to see some tensions. As Pompey’s wife, Caesar’s daughter, died in childbirth, the relationship between the two men was strained. Not long after, in 53 B.C. Crassus, the third man of the alliance, fell in the battle of Carrhae, bringing an end to the triumvirate. When Pompey married the daughter of a political opponent of Caesar, he put the last nail in the coffin of their alliance.

Caesar’s Civil War

In 50 B.C., the Senate, led by Pompey, ordered Caesar – still waging war in Gaul – to disband his army and return to Rome as his term as governor had come to an end and he was being replaced.

Did Caesar follow this order?

Yes and no.

He did return to Rome, but without disbanding his army. Instead, on January 10, 49 B.C., with one of his legions, he crossed the river Rubicon, the boundary between the province Gallia Cisalpina and Italy.

Bringing his army into Italy was nothing else than a declaration of war.

You can read more about the crossing of the river Rubicon, why it was such a big deal and a big surprise to the Senate and Pompey, as well as about the famous quote that refers to this event: Alea iacta est / Iacta alea est, in this article: Iacta Alea est: Crossing the Rubicon

As Caesar and his legion approached Rome, Pompey and many Senators with him, fled to be able to fight another day.

Long story short – this war, simply called The Civil War, between Caesar and Pompey and his allies, was won by Caesar. Pompey was killed in Egypt.

Caesar arrived in Egypt after Pompey’s death and mourned his old friend. He also became involved with a new conflict, the one between the Egyptian queen Cleopatra and her brother-husband, Ptolemy XIII. He famously sided with Cleopatra.

Julius Caesar – Dictator

Caesar was now appointed dictator – i.e. a magistrate of the Roman republic but entrusted with the full authority of the state.

He continued to fight in different parts of the Republic: He went to Asia Minor to fight King Pharnaces II of Pontus, to Africa to fight the remainders of Pompey’s supporters, and also chased Pompey’s sons to Spain.

In spite of all this, Julius Caesar was not all dictator, war, fight, and bloodshed; he was also a reformer.

Caesar extended rights throughout the republic, passed luxury restrictions, rewarded families with many children, created social measures such as the alleviation of debt. And, perhaps most famously, he created a new calendar: the Julian calendar.

The Julian Calendar

The old Roman calendar was based on the moon. By Caesar’s time it was hopelessly confusing and about three months ahead of the solar calendar used by other cultures. After having taken the advice of an astronomer from Alexandria, Caesar replaced the Roman lunar calendar with a calendar that instead was based on the sun. He then set a new length for the year: 365,25 days. Every year had 365 days, but every fourth year an extra day was added in February. However, in order to adjust the out-of-sync Roman year, Caesar turned the year 46 B.C. into an extraordinary one: it contained 445 days.

Does this at all sound familiar?

It should.

The so-called Julian calendar is almost, but not quite, identical to the current western calendar. The current calendar, the Gregorian calendar from the 16th century, has shortened Caesar’s average year by 0,0075 days, which means that the Gregorian calendar skips a leap day in 3 out of every 400 years.

This means that with the exception of ‑0,0075 days in a year, we use the same calendar as the one Julius Caesar introduced.

A small note should perhaps be addressed to the months January and February. It is a common misconception that goes back to the Middle Ages, that Caesar added January and February to the Roman year. The Roman year originally only held 10 months beginning in March ending in December. However, when Caesar reformed the calendar, January and February had already been a part of the Roman year for a very long time. It was (at least according to Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, lib. 1.19) Numa Pompilius that added these months.

But let’s head back to Roman politics:

The End of Julius Caesar

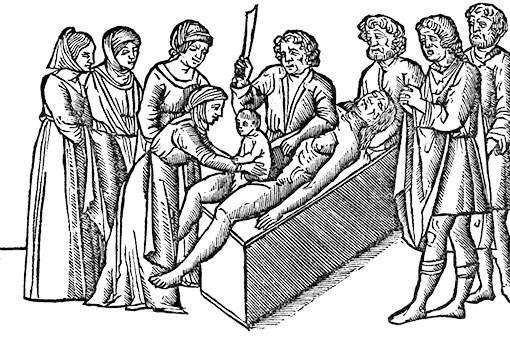

Caesar’s power only grew. Disagreement with his rule in combination with a fear of him wanting to overthrow the Republic and establish a monarchy began to spread amongst the Roman aristocracy and many senators.

These men thus took it upon themselves to save the Republic by assassinating Julius Caesar in the senate on the infamous day the 15th of March 44 B.C. also known as the Ides of March.

Julius Caesar was stabbed 23 times.

Two years later, he was the first Roman to be deified by being granted the title Divus (“Divine”): Divus Iulius.

Works of Julius Caesar

Caesar is famously known as the military general, the politician, and the dictator we have been discussing. What is perhaps less known to those who do not study Latin is that Caesar was regarded as one of the best orators and prose authors of his time. Even Cicero – who rarely agreed with Caesar – held him in high regard on this point and put these words into the mouth of Atticus in his work Brutus:

“illum omnium fere oratorum Latine loqui elegantissime”

— Cicero, Brutus, lxxii

“of all our orators he is the purest user of the Latin tongue”

Unfortunately, Caesar did not, unlike Cicero, publish his speeches.

What we have left from Caesar’s writing are his two commentaries of war:

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico, about the years of his campaigning in Gaul and Britain.

- Commentarii de Bello Civilii, about the civil war with Pompey.

A few letters of his also remain as insertions in Cicero’s correspondence to Atticus.

But Caesar also wrote a grammatical work on analogy, a travel poem, a praise of Hercules, a collection of apothegms, a tragedy called Oedipus, and a work on astronomy. None of these have come down to us.

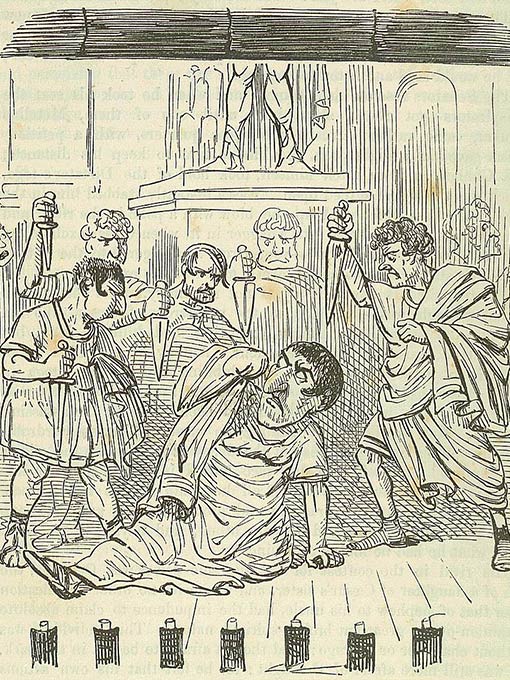

In this chapter of 2000 years of Latin Prose, we shall turn our attention to one of his commentaries on war: De Bello Gallico.

De Bello Gallico contains eight books with each book covering, more or less, one year of Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul (modern France) and southern Britain. This match of one book to one year contributed to the long-lasting belief that De Bello Gallico was written continuously throughout the war. It was believed that the books were written and published annually, almost like “reports from the front”. There is some evidence that Caesar did send reports to the senate, though De Bello Gallico was not it.

No, De Bello Gallico seems instead to have been written all at once, most likely with reports and notes at hand, during the winter of 52–51 B.C.

Book eight, however, was most likely not written by Caesar himself but is believed to have been put together by one of his legates, Aulus Hirtius.

De Bello Gallico is known to most Latin students as it is virtually always part of the curriculum. However, many students only get to read the first part of the first book. We, on the other hand, shall, in today’s Chapter of 2000 years of Latin prose, turn to book five and a passage describing two of Caesar’s centurions: Titus Pullo and Lucius Vorenus. These two have lately been made famous through the TV series Rome; however, the characters in the series are only loosely made up by the men Caesar is describing.

The real Pullo and Vorenus belonged to the garrison of Quintus Tullius Cicero, Cicero’s brother, and in the passage which we will read today their garrison had come under siege. Caesar speaks of the men’s rivalry but also of their bravery. Through their story, we get a glimpse of Romans at war, a chaotic battlefield, and what was considered brave and applaudable to a Roman such as Caesar.

written by Amelie Rosengren, M.A.

Further reading and resources

If you want to know more about Caesar the person, but not feel like reading, you can listen to this text: Caesar and the pirates from Suetonius which you can find in our audio archive.

There is also, as mentioned above, an article about one of Caesar’s most famous sayings: Alea iacta est that you can find here: Iacta Alea Est: Crossing the Rubicon. The article not only discusses the famous line but also gives you more detailed information about the actual crossing of the Rubicon and the political situation of the time.

If you are curious about the TV-series Rome in which the fictional versions of Pullo and Vorenus appear, you can find it here. (It is a phenomenal series, so even if you’re not curious about Pullo and Vorenus, I still recommend watching it if you haven’t already.)

If you want to learn even more about Caesar and his works and literary style, I warmly recommend Michael von Albrecht’s A History of Roman Literature: From Livius Andronicus to Boethius or The Cambridge companion to the writings of Julius Caesar, edited by Luca Grillo, Christopher B. Krebs.

Audio & Video

Click below to read and listen to a passage from Caesar’s De Bello Gallico.

Video with English Subtitles

Audio of Latin text

Latin text

Below you will find the original text of the passage from De Bello Gallico in Latin.

De Bello Gallico, 5.44

Erant in ea legione fortissimi viri, centuriones, qui primis ordinibus appropinquarent, Titus Pullo et Lucius Vorenus. Hi perpetuas inter se controversias habebant, quinam anteferretur, omnibusque annis de locis summis simultatibus contendebant. Ex his Pullo, cum acerrime ad munitiones pugnaretur, “Quid dubitas,” inquit, “Vorene? aut quem locum tuae probandae virtutis exspectas? Hic dies de nostris controversiis iudicabit.”

Haec cum dixisset, procedit extra munitiones quaque pars hostium confertissma est visa irrumpit. Ne Vorenus quidem tum sese vallo continet, sed omnium veritus existimationem subsequitur. Tum, mediocri spatio relicto Pullo pilum in hostes immittit atque unum ex multitudine procurrentem traicit; quo percusso et exanimato hunc scutis protegunt, in hostem tela universi coniciunt neque dant regrediendi facultatem. Transfigitur scutum Pulloni et verutum in balteo defigitur. Avertit hic casus vaginam et gladium educere conanti dextram moratur manum, impeditumque hostes circumsistunt. Succurrit inimicus illi Vorenus et laboranti subvenit.

Ad hunc se confestim a Pullone omnis multitudo convertit: illum veruto arbitrantur occisum. Gladio comminus rem gerit Vorenus atque uno interfecto reliquos paulum propellit; dum cupidius instat, in locum deiectus inferiorem concidit. Huic rursus circumvento fert subsidium Pullo, atque ambo incolumes compluribus interfectis summa cum laude sese intra munitiones recipiunt.

Sic fortuna in contentione et certamine utrumque versavit, ut alter alteri inimicus auxilio salutique esset, neque diiudicari posset, uter utri virtute anteferendus videretur.

Vocabulary & Commentary

These following words are key to understanding the text, if you already know them — great! — if not, make a mental note of them.

primis ordinibus appropinquarent: Pullo and Vorenus, both centurions, wanted to become centurions of the first cohort, thus the senior centurions of the legion (Gaisser).

perpetuas inter se controversias: i.e. they were always in contest over who was the best and most deserving of being promoted.

cum–pugnaretur: i.e. when there was fighting going on

Ne Vorenus quidem: Ne–quidem usually means ”not even” but here is is clear that the meaning is rather the opposite “of course–not”.

qua: adv. where, quaque ”and where, whither”

scutum Pulloni: lit. ”the shield for Pullo”. This is a so-called dativus incommodi (”dative of disadvantage”) where the person who suffers the disadvantage is placed in the dative. This is especially common with blows and hits, e.g. illi caput percussit (“He struck his (lit. for him) head”). This construction also lays the focus on the object rather than the person.

quo percusso et exanimato, hunc scutis protegunt: Here Caesar ”violates” the school rule of the ablative absolute.This occurs throughout classical literature, and shows that these rules are not unbreakable laws, but rather strong tendencies.

gladium ēdūcere cōnantī dextram moratur manum: another example of the dative of disadvantage: ”delays the right hand of him (lit. for him) trying to pull out his sword”

appropinquo, ‑are: approach

controversia, ‑ae f.: controversy, quarrel, dispute

simultas, ‑atis f.: feud, quarrel

contendo, ‑dere, ‑di, ‑tum: fight over, strain

irrumpo, ‑ere, ‑rupi, ‑ruptum: burst into, dart upon

verutum, ‑i n.: javelin

balteus, ‑i m.: sword belt

averto, ‑ere, ‑ti, ‑sum: to turn aside

diiudico, ‑are: decide

antefero, ‑ferre: prefer

munitio, ‑onis f.: construction, fortification

iudico, ‑are: to judge

confertus, ‑a, ‑um: condensed

existimatio, ‑onis f.: opinion, reptutation

subsequor, ‑i, ‑secutus: follow closely

mediocris, ‑e: moderately large

immitto, ‑mittere, ‑misi, ‑missum: to send in

procurro, ‑currere, ‑cucurri, ‑cursum: to rush forwards

traicio, ‑ire, ‑ieci, ‑iectum: to pierce

percutio, ‑ire, ‑cussi, ‑cussum: to strike, thrust, or pierce through

exǎnimo, ‑are: to deprive of breath; to kill

scutum, ‑i n.: an oblong shield

protego, ‑ere, ‑xi, ‑ctum: cover

conicio, ‑ire, ‑ieci, ‑iectum: to bring together, unite; to hurl

regredior, ‑i, ‑gressus: to come or go back; retreat

fǎcultas, ‑atis f.: opportunity

transfigo, ‑ere, ‑xi, ‑xum: pierce

defigo, ‑ere, ‑xi, ‑xum: plant firmly, fix

impedio, ‑ire, ‑ivi, ‑itum: to entangle, hinder

circumsisto, ‑sistere, ‑steti: to surround

succurro, ‑ere, ‑curri, ‑cursum: run to aid

subvenio, ‑ire, ‑veni, ‑ventum: to come to one’s assistance

confestim: immediately

comminus adv.: in hand to hand combat

propello, propellere, ‑puli, ‑pulsum: to drive, push, urge forward

cupidus, ‑a, ‑um: eager

insto, instare, ‑stiti, ‑stǎtum: to press upon, pursue

deicio, ‑ere, ‑ieci, ‑iectum: throw down from; drive

circumvenio, ‑ire, ‑veni, ‑ventum: to come around; encircle; surround

subsidium, ‑ii n.: help, aid; troops stationed in reserve

ambo: both together

incolumis, ‑e: unharmed, uninjured

complures, ‑ia, ‑ium: several

contentio, ‑onis f.: struggle, contest

English translation

Below you will find an English translation of the text.

De Bello Gallico, 5.44

In that legion there were two very brave men, centurions, who were now approaching the first ranks, T. Pullo, and L. Vorenus. These used to have continual disputes between them which of them should be preferred, and every year used to contend for promotion with the utmost animosity. When the fight was going on most vigorously before the fortifications, Pullo, one of them, says, “Why do you hesitate, Vorenus? or what [better] opportunity of showing your valor do you seek? This very day shall decide our disputes.”

When he had uttered these words, he proceeds beyond the fortifications, and rushes on that part of the enemy which appeared the thickest. Nor does Vorenus remain within the rampart, but respecting the high opinion of all, follows close after. Then, when an inconsiderable space intervened, Pullo throws his javelin at the enemy, and pierces one of the multitude who was running up, and while the latter was wounded and slain, the enemy cover him with their shields, and all throw their weapons at the other and afford him no opportunity of retreating. The shield of Pullo is pierced and a javelin is fastened in his belt. This circumstance turns aside his scabbard and obstructs his right hand when attempting to draw his sword: the enemy crowd around him when [thus] embarrassed.

His rival runs up to him and helps him in this emergency. Immediately the whole host turn from Pullo to him, supposing the other to be pierced through by the javelin. Vorenus rushes on briskly with his sword and carries on the combat hand to hand, and having slain one man, for a short time drove back the rest: while he urges on too eagerly, slipping into a hollow, he fell. To him, in his turn, when surrounded, Pullo brings relief; and both having slain a great number, retreat into the fortifications amid the highest applause.

Fortune so dealt with both in this rivalry and conflict, that the one competitor was a help and a safeguard to the other, nor could it be determined which of the two appeared worthy of being preferred to the other.

Translated by McDevitte and Bohn (1869)