Contents

Two thousand years of Latin Prose is a digital anthology of Latin Prose. Here you will be able to find texts from two millennia of gems in Latin. In this eighth chapter, we will learn more about Varro. We will also read about how to harvest grapes for wine in a passage from his work De Re Rustica.

If you want to learn more about the anthology, you will find the preface here.

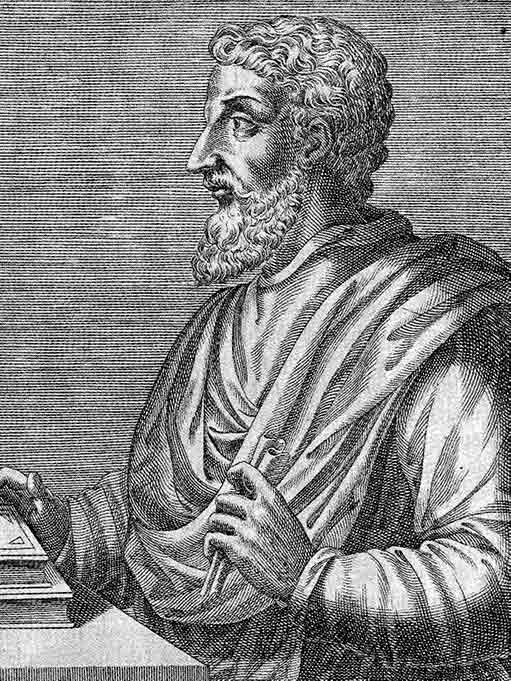

Life and Works of Marcus Terentius Varro

(116–27 B.C.)

Marcus Terentius Varro was perhaps Rome’s greatest scholar and a contemporary of Cicero and Caesar.

Life of Varro

Varro was born in 116 B.C. probably in Reate (modern Rieti, Lazio, Italy), where he also owned estates. Due to his birthplace, and, to separate him from a slightly younger namesake, the poet Publius Terentius Varro Atacinus (82‑c. 35 B.C.), he sometimes referred to as Varro Reatinus.

Saint Augustine (354–430 A.D.), however, did not agree with Varro’s origin being Reate, but insisted that he was born and bred in Rome itself:

“Quod profecto non auctoritate sua fecit, sed quoniam eos Romae natus et educatus in divinis rebus invenit. ”

— Augustinus, Civ, 4.1

And this he did not on his own authority, but because, being born and educated at Rome, he found them among the divine things.

Whether or not Augustine was right or not, we will never know. What we do know is that Varro had a thorough education in Rome and in Athens, with teachers such as the grammarian Lucius Auelius Stilo and philosopher Antioch of Ascalon.

Varro later became involved in politics, becoming quaestor, tribune, and later – although this is uncertain – praetor and was part of the commission charged with executing the agrarian law of Julius Caesar, which distributed land among the poor.

Varro was also a close friend of Pompey, or Pompeius Magnus, and helped him fight pirates in the Mediterranean and stood by his side as a senior officer in the civil war against Julius Caesar. (For more about Caesar, see Chapter 6 of this anthology.)

After the death of Pompeius Magnus, Caesar chose to pardon Varro and, according to Suetonius, charged him with the task of organizing the public library that he had planned. Varro was to obtain and classify Greek and Latin literature to open the most magnificent public library possible. (See: Suetonius, Div. Iul. 44).

The plans for a library and Varro’s pardon came to a brutal end in 44 B.C. with Caesar’s assassination. In the aftermath, Varro was outlawed by Marcus Antonius, and his villa, including his private library, was destroyed.

Along with his possessions, Varro’s life was in jeopardy, but it was saved by a friend, general, and consul Quintus Fufius Calenus, who fortunately was on Marcus Antonius’ good side.

Once Emperor Augustus came into power, Varro gained his protection and spent the rest of his life writing in peace. He died of old age in 27 B.C.

Varro’s works

Varro didn’t just write at the end of his life. He wrote throughout, and it has been estimated that he produced more than 74 Latin works (as well as a few Greek) spanning over more than 600 books. He was a giant in his own time, and he was often referred to as a source for other authors.

So great did Varro’s contemporaries think of the scholar and his writings that when consul, soldier, poet, and historian Gaius Asinius Pollio (75 B.C.-4 A.D.) founded a public library in Rome (not the one Caesar had planned), a statue of Varro was placed in it. There were many statues in the library, but Varro’s was the only of a living person (See: Plinius, Nat Hist. VII.30).

Quintilian (c.35‑c.100 A.D.), though not a contemporary, even called him vir Romanorum eruditissimus, i.e. the most learned of all Romans. (See Quintillian’s Institutio Oratoria, lib X.95)

Varro composed works in many genres such as literary history, rhetoric, philosophy, and poetry, as well as books concerning the genres of Roman poetry, the origin of the Roman people. He also wrote an illustrated book about Greek and Roman political life — the first known illustrated Roman book. Supposedly this last work had 700 pictures of famous Romans and Greeks.

Varro’s perhaps most important work, though lost to us today, was his Disciplinae, an encyclopedia of the nine liberal arts; grammar, dialectic, rhetoric, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, music, medicine, and architecture. This work became a model for later encyclopedists and lay the foundation for the later defined seven classical liberal arts.

Another essential work, though perhaps less literary, was Varro’s chronology, known as the Varronian Chronology. This chronology was a year-by-year timeline of Roman history up to Varro’s own time based on the sequence of consuls of the Roman republic. The chronology has been proved wrong in several cases. It was, however, inscribed on the Arch of Augustus in Rome (the arch no longer stands) and was used as a basis for the Fasti Capitolini – a list of the chief magistrates from the early 5th century B.C. to Emperor Augustus’ time originally engraved on marble tablets at the Forum Romanum. These, together with later historians such as Livius, largely form our knowledge of Roman chronology.

Most of Varro’s enormous corpus of writings has, as mentioned, been lost to us. We do have fragments from many of them – mostly preserved in Aulus Gellius (125–180 A.D.) Noctes Atticae.

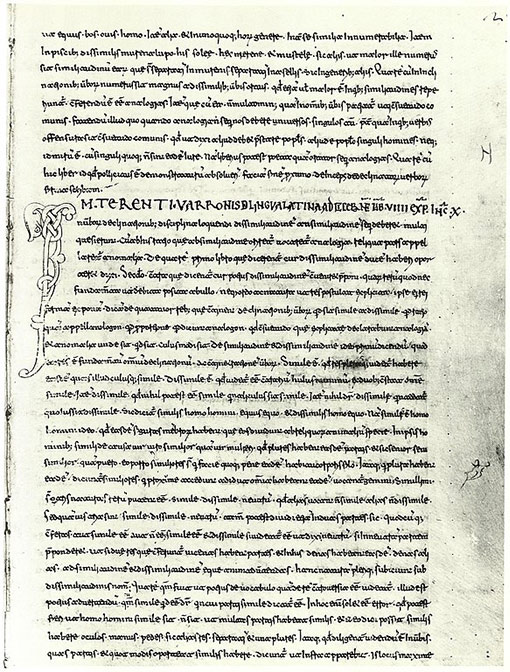

There are two of Varro’s works from which more has been preserved from De Re Rustica sive Rerum Rusticarum libri III and De Lingua Latina.

De Lingua Latina was Varro’s grammatical work, written between 47 and 45 B.C. It consisted originally of 25 books, out of which we only have 6 left (books V‑X) however, in a poor, gap-filled state.

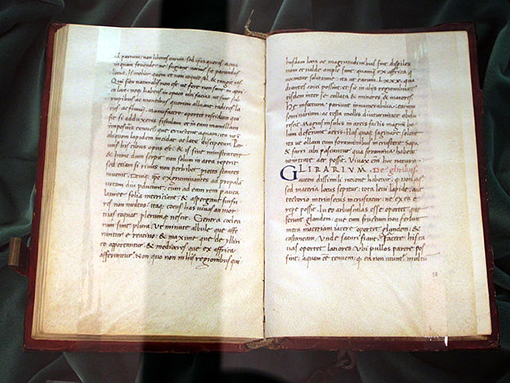

De Re Rustica, is the only one preserved in its entirety. It is, as the title indicates, a work about agriculture. It is written in three books where the first one concerns agriculture, the farming of land, the second cattle, and the third one raising small livestock (birds, bees etc.).

It is to De Re Rustica we shall turn to today’s chapter of 2000 years of Latin Prose and read a passage about grapes and wine.

Further reading and resources

- You can read more about Varro and the civil war in Julius Caesar’s Bellum Civile, lib. II.17–21. Be aware though, the book is written by Caesar so he might be a little bit biased.

- Michael von Albrecht’s A History of Roman Literature: From Livius Andronicus to Boethius or The Cambridge companion to the writings of Julius Caesar, edited by Luca Grillo, Christopher B. Krebs, is a treasure when learning about Roman authors and their literary styles.

- Lives of Caius Asinius Pollio, Marcus Terentius Varro, and Cneius Cornelius Gallus; with illustrations, by Edward Berwick (1814) — Though beware that this book is not a modern history book and has a lot of opinions, fluffed details and takes a lot of liberties. It is a good read, though, and gives a more complete picture of Varro.

Audio & Video

Click below to read and listen to a passage from Varro’s De Re Rustica.

Video With English Subtitles

Audio of Latin Text

Latin text

Below you will find the original text of the passage in Latin.

De Re Rustica, lib I. LIV

In vinetis uva cum erit matura, vindemiam ita fieri oportet, ut videas, a quo genere uvarum et a quo loco vineti incipias legere. Nam et praecox et miscella, quam vocant nigram, multo ante coquitur, quo prior legenda, et quae pars arbusti ac vineae magis aprica, prius debet descendere de vite.

In vindemia diligentis uva non solum legitur sed etiam eligitur; legitur ad bibendum, eligitur ad edendum. Itaque lecta defertur in forum vinarium, unde in dolium inane veniat; electa in secretam corbulam, unde in ollulas addatur et in dolia plena vinaciorum contrudatur, alia quae in piscinam in amphoram picatam descendat, alia quae in aream in carnarium escendat. Quae calcatae uvae erunt, earum scopi cum folliculis subiciendi sub prelum, ut, siquid reliqui habeant musti, exprimatur in eundem lacum.

Cum desiit sub prelo fluere, quidam circumcidunt extrema et rursus premunt et, rursus cum expressum, circumsicium appellant ac seorsum quod expressum est servant, quod resipit ferrum. Expressi acinorum folliculi in dolia coniciuntur, eoque aqua additur; ea vocatur lora, quod lota acina, ac pro vino operariis datur hieme.

Vocabulary & Commentary

These following words are key to understanding the text, if you already know them — great! — if not, make a mental note of them.

vinetum, ‑i, n. vineyard. Note that the ending -etum commonly indicates that there is a collection of a particular tree or bush. Compare e.g. with olivetum, and quercetum meaning “olive-grove” and “oak-forest” respectively.

vindemia, ‑ae, f., vintage, harvest of grapes

quo, adv. wherefore, and therefore

apricus, ‑a, um, adj. sunny

lego, legere, gather, pick

vinacea, ‑orum, n. pl. wine dregs

scopus, ‑i, m. stalk

resipit ferrum, tastes of iron; in Latin, the taste, or smell something has, is expressed by the accusative with verbs such as olet, resipt, sapit (it smells, it tastes). Another example would be hoc vinum piscem sapit. (“This wine tastes of fish”)

quod lota aqua, here we have to supply est. In Latin it is very common to leave out forms of esse, when they can be easily inferred from the context.

English translation

Below you will find an English translation of the text.

On Agriculture, Book I. LIV

As to vineyards, the vintage should begin when the grapes are ripe; and you must choose the variety of grapes and the part of the vineyard with which to begin. For the early grapes, and the hybrids, the so‑called black, ripen much earlier and so must be gathered sooner; and the part of the plantation and vineyard which is sunnier should have its vines stripped first.

At the vintage the careful farmer not only gathers but selects his grapes; he gathers for drinking and selects for eating. So those gathered are carried to the wine-yard, thence to go into the empty jar; those selected are carried to a separate basket, to be placed thence in small pots and thrust into jars filled with wine dregs, while others are plunged into the pond in a jar sealed with pitch, and still others go up to their place in the larder. When the grapes have been trodden, the stalks and skins should be placed under the press, so that whatever must remains in them may be pressed out into the same vat.

When the flow ceases under the press, some people trim around the edges of the mass and press again; this second pressing is called circumsicium,and the juice is kept separate because it tastes of the knife. The pressed grape-skins are turned into jars and water is added; this liquid is called lora, from the fact that the skins are washed (lota), and it is issued to the labourers in winter instead of wine.