Contents

Two thousand years of Latin Prose is a digital anthology of Latin Prose. Here you will be able to find texts from two millennia of gems in Latin. In this ninth chapter, we will learn more about Sallustius, known to many as Sallust. We will also read a passage from his most famous work Bellum Catilinae.

If you want to learn more about the anthology, you will find the preface here.

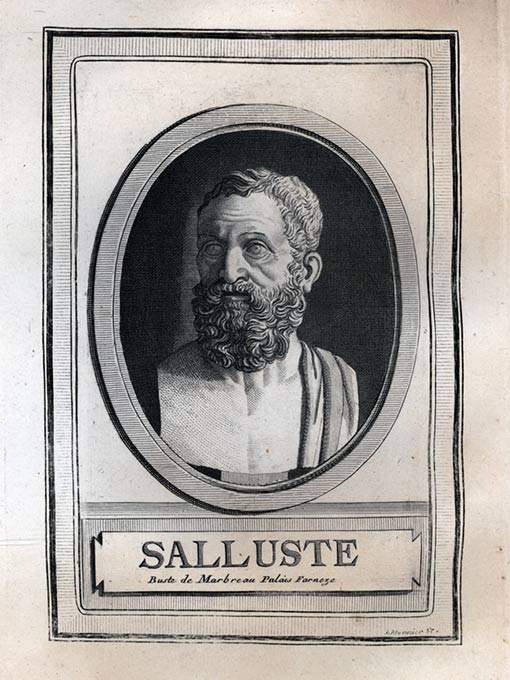

Life and works of Gaius Sallustius Crispus

In this section you will learn about the life and works of Sallustius.

(86–35 B.C)

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, or simply Sallust, was a Roman politician and historian, probably born in Amiternum in central Italy.

Life of Sallustius

Of Sallustius’ early years, we know very little, hardly anything. It is not until the 50’s B.C. that we have more than speculation to go on.

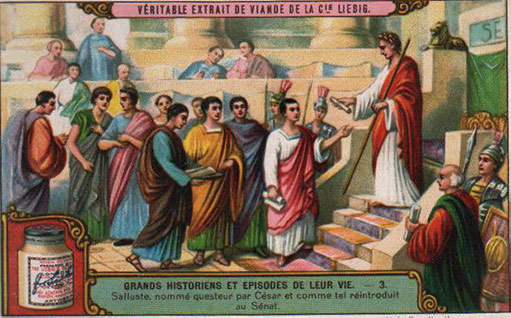

Prior to 52 B.C. Sallustius might have been a quaestor, though this has been disputed. In 52 B.C., he became a Tribune of the Plebs. However, two years later, in 50 B.C., he was, along with some others, driven from the senate. This was perhaps (but nothing is certain) due to his sympathies towards Julius Caesar, a man he would support and later thank for his life.

Caesar later appointed Sallustius commander of a legion. Even though he did not stand out militarywise, he was rewarded for his support and loyalty by being appointed governor of the province Africa Nova (the old Kingdoms of Numidia and Mauretania in northwestern Africa).

Sallustius was not a good governor. If we are to believe historian Dio Cassius (155–235 A.D.), he was a terrible, oppressive governor. According to Cassius (lib 43.9), he harassed and plundered his subjects, confiscated property, and took bribes to line his own pockets. When he returned to Rome, sometime around 45 or 44 B.C., it was only thanks to Julius Caesar that he escaped charges.

Sallustius turned away from public life, perhaps after Caesar’s death, though the exact time for his withdrawal is uncertain. He then spent the rest of his days writing historical literature and developing his gardens, the Horti Sallustiani.

Sallustius life was a little bit of a contradiction:

On the one hand, we have an active politician whose writings, that we soon shall turn to, are (amongst other things) famous for their stern critique of the loose morality of the Roman aristocracy and for their concern about Rome’s moral decline.

On the other hand, we have a man who oppressed the region he was supposed to govern and was infamous for his loose living.

For example, Aulus Gellius relates a story from Varro about when Sallustius was caught, red-handed, by Titus Annius Milo (known from Cicero’s speech Pro Milone) committing adultery. Rumour has it that the woman Sallustius was sleeping with was none other than Milo’s own wife Fausta Cornelia, daughter of Sulla. Gellius does not point her out; however, Milo’s reaction to Sallustius’ indiscretion speaks for itself: he beat the author with thongs and refused to let him leave until Sallustius had paid him a sum of money.

“in adulterio deprehensum ab Annio Milone loris bene caesum dicit et, cum dedisset pecuniam, dimissum. ”

— Aulus Gellis, lib. XVII.xviii

Dio Cassius, though not a contemporary, harshly remarks that Sallustius did not practice what he preached. (Dio Cass. 43. 9)

Works of Sallustius

Three of Sallustius’ works remain today; Fragments of the Historiae, Bellum Iugurthinum, and Bellum Catilinae.

The Historiae was a continuation of Cornelius Sisenna’s (120–67 B.C.) now lost work, also called Historiae. Sisenna’s work was a history covering the years 90 B.C. to 78 B.C.

Sallustius’ Historiae began where Sisenna’s work ended, 78 B.C. and continued to the year 67 B.C. It would have continued onwards, but Sallustius died before he could finish it.

Today we have parts left from the Historiae; four speeches, two letters, and about 500 fragments.

Bellum Iuguthinum was written around 40 B.C. and deals with the Jugurthine War (111–105 B.C.) fought between Jugurtha, king of Numidia, and Rome.

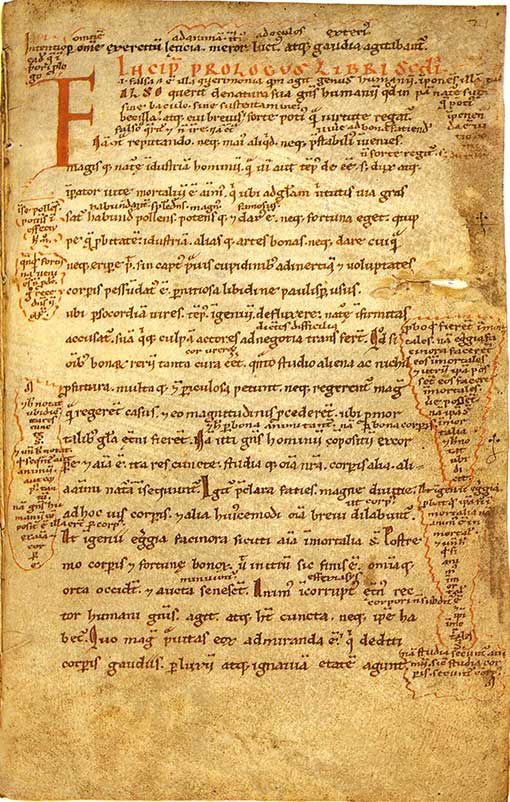

Bellum Catilinae is the most famous of Sallustius’ works and was perhaps written around 42 B.C. as his first published work. It is also to this work we shall turn in today’s chapter to sample his writings.

Bellum Catilinae goes through the Catiline Conspiracy of 63 B.C. that we have already heard a little bit about in this digital Anthology’s Chapter 5: Cicero and his De Catilina.

The conspiracy was a plot to overthrow the Roman Republic and was named after the main conspirator, Lucius Sergius Catilina. Though the conspiracy happened during Sallustius’ life, he was most likely not in Rome at the time but instead was in the military service. His Bellum Catilina is not written around the time of the conspiracy in the 60’s B.C. but between 44 and 40 B.C. Thus, ca. 20 years had passed in between the actual events and the book.

The passage we shall be looking at today is the beginning of Bellum Catilina. Sallustius is not one to go straight to the point but instead sets the tone of his work with this passage with thoughts on the mind, body, and glory.

Further reading and resources

- If you can’t get enough of Sallustius and Bellum Catilinae, you can listen to two other passages in our audio archive: Sallust on the death of Catiline and Catilina coniuratos hortatur.

- If you are a Patron on Patreon.com/latinitium, you can also find a video lesson on the part chapter of Bellum Catilinae where Daniel goes through the text; you can find it here. As a Patron, you can also find a video lesson on Sallustius’ passage on the death of Catiline: Exitus Catilinae, as well as one of his “fake speeches”: Ficta Marii Oratio.

- Michael von Albrecht’s A History of Roman Literature: From Livius Andronicus to Boethius or The Cambridge companion to the writings of Julius Caesar, edited by Luca Grillo, Christopher B. Krebs, is a treasure when learning about Roman authors and their literary styles.

Audio & Video

Click below to read and listen to a passage from Sallustius’ Bellum Catilinae.

Video With English Subtitles

Audio Of Latin Text

Latin Text

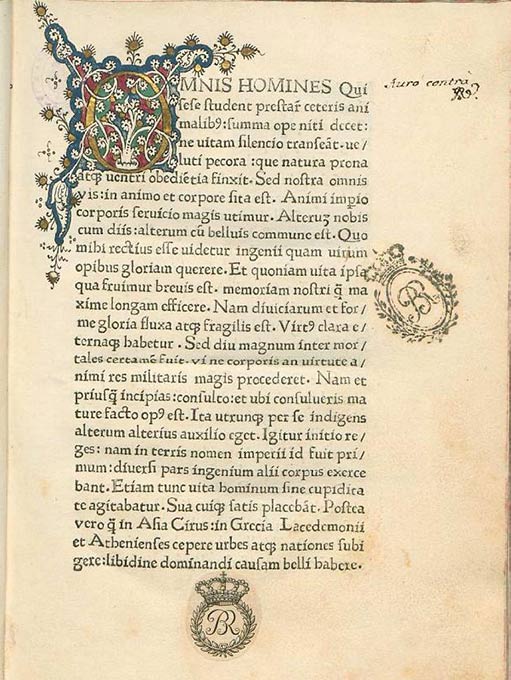

Below you will find the original text of the passage in Latin.

Bellum Catilinae, 1.1–3

Omnis homines, qui sese student praestare ceteris animalibus, summa ope niti decet, ne vitam silentio transeant veluti pecora, quae natura prona atque ventri oboedientia finxit. Sed nostra omnis vis in animo et corpore sita est: animi imperio, corporis servitio magis utimur; alterum nobis cum dis, alterum cum beluis commune est. Quo mihi rectius videtur ingeni quam virium opibus gloriam quaerere et, quoniam vita ipsa, qua fruimur, brevis est, memoriam nostri quam maxume longam efficere. Nam divitiarum et formae gloria fluxa atque fragilis est, virtus clara aeternaque habetur. Sed diu magnum inter mortalis certamen fuit, vine corporis an virtute animi res militaris magis procederet. Nam et, prius quam incipias, consulto et, ubi consulueris, mature facto opus est. Ita utrumque per se indigens alterum alterius auxilio eget.

Igitur initio reges – nam in terris nomen imperi id primum fuit – divorsi pars ingenium, alii corpus exercebant: etiam tum vita hominum sine cupiditate agitabatur; sua cuique satis placebant. Postea vero quam in Asia Cyrus, in Graecia Lacedaemonii et Athenienses coepere urbis atque nationes subigere, lubidinem dominandi causam belli habere, maxumam gloriam in maxumo imperio putare, tum demum periculo atque negotiis compertum est in bello plurumum ingenium posse. Quod si regum atque imperatorum animi virtus in pace ita ut in bello valeret, aequabilius atque constantius sese res humanae haberent neque aliud alio ferri neque mutari ac misceri omnia cerneres. Nam imperium facile iis artibus retinetur, quibus initio partum est. Verum ubi pro labore desidia, pro continentia et aequitate lubido atque superbia invasere, fortuna simul cum moribus inmutatur. Ita imperium semper ad optumum quemque a minus bono transfertur. Quae homines arant, navigant, aedificant, virtuti omnia parent. Sed multi mortales, dediti ventri atque somno, indocti incultique vitam sicuti peregrinantes transiere; quibus profecto contra naturam corpus voluptati, anima oneri fuit. Eorum ego vitam mortemque iuxta aestumo, quoniam de utraque siletur. Verum enim vero is demum mihi vivere atque frui anima videtur, qui aliquo negotio intentus praeclari facinoris aut artis bonae famam quaerit. Sed in magna copia rerum aliud alii natura iter ostendit.

Pulchrum est bene facere rei publicae, etiam bene dicere haud absurdum est; vel pace vel bello clarum fieri licet; et qui fecere et qui facta aliorum scripsere, multi laudantur. Ac mihi quidem, tametsi haudquaquam par gloria sequitur scriptorem et actorem rerum, tamen in primis arduum videtur res gestas scribere: primum, quod facta dictis exaequanda sunt; dehinc, quia plerique, quae delicta reprehenderis, malevolentia et invidia dicta putant, ubi de magna virtute atque gloria bonorum memores, quae sibi quisque facilia factu putat, aequo animo accipit, supra ea veluti ficta pro falsis ducit.

Explained In Latin

If you are a Patron on Patreon.com/latinitium, you can also find a video lesson on the first part, 1.1, of Bellum Catilinae where Daniel goes through the text, you can find it here.

Vocabulary & Commentary

These following words are key to understanding the text, if you already know them — great! — if not, make a mental note of them.

sese præstare: acc. and inf. after student, a rare constr. instead of the simple inf., which is the rule after verbs of wishing, seeking, etc., when the subject of both verbs is the same. In Cicero and Caesar the reflexive pronoun is generally expressed after verbs of wishing and striving only when the infinitive takes a pred. noun or adj. (Ramsey 1984), e.g. gratum se videri studet, ‘he is anxious to seem pleasing’ (Cic., de Off. ii. 20. 7.). Some editors think that the insertion of the pron. sese gives special emphasis, others that it is a colloquialism or archaism.

summa ope: Instead of the more common summopere, likely to add an archaic flavour. (McGushin 1980)

silentio: pass, sense, ‘not spoken about,’ ‘in obscurity,’ or ‘unnoticed.’

prona finxit: ‘whom nature has made to gaze on the ground and serve their belly’; ventri, i. e. the natural appetites.

Sed nostra omnis vis: ‘Now our capacity, taken as a whole, resides in the mind and the body jointly; we employ the governance of the mind, the service rather of the body (or more freely, ‘the mind is the ruling, the body rather the serving element in us’). For omnis cf. Caesar’s Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres (B. G. I. 1.). Sed is not adversative and only introduces a new concept (McGushin 1980).

alterum…alteram: refers loosely to animus and corpus, ‘the one we share with the gods, the other with the beasts.’

quo mihi rectius videtur: ‘and so it seems to me more reasonable to seek glory…’; quo is simply ‘and therefore,’ and should not be taken with rectius; Some editors, however, take quo as the common abl. with the comp. rectius(‘by which…the more reasonable’) and explain by an ellipse, quanto di præstant beluuis tanto rectius mihi videtur, ‘in proportion as gods surpass beasts, so much the more reasonable does it seem to me.’

vita ipsa qua fruimur: our life on earth contrasted with the legacy and memory that lives on after our time. (McGushin 1980)

fluxa atque fragilis: alliterative,’fleeting and frail.’

virtus…habetur: ‘merit is a noble and eternal possession’; habetur: not ‘is considered,’ but ‘is a possession’.

mortalīs: Sallust uses omnes homines and omnes mortales indifferently and there is nothing to support the view that it is used because it is an archaic word. (McGushin 1980)

nam et…prius opus est: the present and perfect subjunctive with the second person refers to an undefined person ‘you’, ‘one’; ‘for there is need both of deliberation before one begins, and of well-timed action after one has deliberated.’

utrumque: ‘each, incomplete by itself, needs the help the one of the other’, i. e., ‘needs the other’s help’; alterum resumes the utrumque.

igitur: Sall. puts igitur as the first word except in questions. This is an archaism. (McGushin 1980)

divorsi pars… alii: ‘taking opposite courses, some employed the intellect, others the bodily powers’; pars, alii, inpartitive apposition to reges; pars is often opposed by Sall. to alii, multi, pauci, to give variety, instead of the regular pars…pars.

agitabatur:‘to live’, an archaich use. Sall., is especially fond of frequentative forms.

lubidinem…habere: ‘to have in their lust for rule a pretext for war, to find the greatest glory in the greatest empire.’

periculo atque negotiis: ‘it was found out by experience’. Nonius 578L quotes this phrase to show that periculum is sometimes equivivalent to experimentum. (McGushin 1980)

regum atque imperatorum animi virtus: the intellectual excellence (or ‘ability’) of kings and rulers’; imperatores in a wider sense than regum, not in the technical Roman sense of ‘military commanders’.

neque aliud … cerneres: ‘nor would you have seen constant shiftings to and fro, and the whole world in a state of change and confusion’; alio, adverb.

iis artibus: ‘by those qualities’ or ‘means’; artes, a favourite word of Sall., especially in phrases bonae artes, ‘virtues’; malae artes, ‘vices.’

invasere: as we say ‘have come in’ in sense of ‘have become common’; a favourite word of Sall.; here used absol., but usually with acc. or in and acc.

quae: cognate acc. to the three verbs, arant, navigant, aedificant; lit.’ the ploughings which men plough, the sailings which they sail, etc.’; each of the three phrases, quae arant, etc., is equiv. to a subst., and the three, taken up and repeated by omnia, are subj. of parent: ‘whether men plough, or sail the sea or build, everything they do depends upon merit’ (or ‘upon energy’). McGushin (1980) paraphrases the sentence for clarity as quae homines arando, navigando, aedificando efficunt.

sicuti peregrinantes: i. e. passing carelessly through life without real knowledge or study of its possibilities, as a tourist does not trouble to study a land in which he is only temporarily settled.

iuxta aestumo: ‘I value alike,’ i. e. at an equally low rate; for iuxta = ‘equally,’

is demum…: ‘that man, and that man alone, seems to me to live and have real enjoyment of his vital powers…’

negotio intentus: Commentators dispute whether the case in this and similar phrases (proelio intentus, etc.) is dat. or abl.; prob. the latter, intentus keeping its participial force, ‘kept on the stretch by…’; intentus is generally used absolutely.

bene facere rei publicae: facere contrasted with dicere, hence transl. here not ‘to benefit the state,’ but ‘to act well for the advantage of the state,’ ‘to benefit the state by action.’

bene dicere: is used absolutely, and does not govern rei publicae.

laudantur: its subj. is the antecedent of qui fecere, qui scripsere, to which multi is added in apposition; transl. ‘many, both those who have done great deeds, and those who have described the deeds of others, win praise.’

primum: three reasons are given introd. by primum, dehinc, ubi de.

facta dictis exaequanda sunt: lit. ‘the deeds must be matched by the words.’ as we might say, ‘noble actions must be worthily described’; dictis, abl. of means.

plerique…: ‘most men think that the faults you have censured (quae delicta reprehenderis) have been mentioned (dicta) out of spite and envy.’

supra ea: for quae supra ea sunt, ‘what goes beyond that he regards as false (pro falsis), as though it were a mere invention (veluti ficta).’

ambitione corrupta tenebatur: better (1) corrupta nom., agreement with aetas, ‘was seduced and held prisoner by a love of honour’ than (2) as Dietsch, corrupta, abl. agreement with ambitione, ‘by a corrupt’ or ‘corrupting ambition.’

honoris cupido eadem qua ceteros…: the order is honoris cupido vexabat me eadem fama atque invidia qua ceteros (vexabat), ‘the desire for the honours of office caused me to be dogged with the same slander and jealousy as the rest (of my competitors)’; fama in sense of mala fama.

English Translation

Below you will find an English translation of the text.

The Catiline War, 1.1–3

It behooves all men who wish to excel the other animals to strive with might and main not to pass through life unheralded, like the beasts, which Nature has fashioned grovelling and slaves to the belly. All our power, on the contrary, lies in both mind and body; we employ the mind to rule, the body rather to serve; the one we have in common with the Gods, the other with the brutes. Therefore I find it becoming, in seeking renown, that we should employ the resources of the intellect rather than those of brute strength, to the end that, since the span of life which we enjoy is short, we may make the memory of our lives as long as possible. For the renown which riches or beauty confer is fleeting and frail; mental excellence is a splendid and lasting possession.

Yet for a long time mortal men have discussed the question whether success in arms depends more on strength of body or excellence of mind; for before you begin, deliberation is necessary, when you have deliberated, prompt action. Thus each of these, being incomplete in itself, requires the other’s aid.

Accordingly in the beginning kings (for that was the first title of sovereignty among men), took different courses, some training their minds and others their bodies. Even at that time men’s lives were still free from covetousness; each was quite content with his own possessions. But when Cyrus in Asia and in Greece the Athenians and Lacedaemonians began to subdue cities and nations, to make the lust for dominion a pretext for war, to consider the greatest empire the greatest glory, then at last men learned from perilous enterprises that qualities of mind availed most in war.

Now if the mental excellence with which kings and rulers are endowed were as potent in peace as in war, human affairs would run an evener and steadier course, and you would not see power passing from hand to hand and everything in turmoil and confusion; for empire is easily retained by the qualities by which it was first won. But when sloth has usurped the place of industry, and lawlessness and insolence have superseded self-restraint and justice, the fortune of princes changes with their character. Thus the sway is always passing to the best man from the hands of his inferior. Success in agriculture, navigation, and architecture depends invariably upon mental excellence. Yet many men, being slaves to appetite and sleep, have passed through life untaught and untrained, like mere wayfarers in these men we see, contrary to Nature’s intent, the body a source of pleasure, the soul a burden. For my own part, I consider the lives and deaths of such men as about alike, since no record is made of either. In very truth that man alone lives and makes the most of life, as it seems to me, who devotes himself to some occupation, courting the fame of a glorious deed or a noble career. But amid the wealth of opportunities Nature points out one path to one and another to another.

It is glorious to serve one’s country by deeds; even to serve her by words is a thing not to be despised; one may become famous in peace as well as in war. Not only those who have acted, but those also who have recorded the acts of others oftentimes receive our approbation. And for myself, although I am well aware that by no means equal repute attends the narrator and the doer of deeds, yet I regard the writing of history as one of the most difficult of tasks: first, because the style and diction must be equal to the deeds recorded; and in the second place, because such criticism as you make of others’ shortcomings are thought by most men to be due to malice and envy. Furthermore, when you commemorate the distinguished merit and fame of good men, while every one is quite ready to believe you when you tell of things which he thinks he could easily do himself, everything beyond that he regards as fictitious, if not false.

When I myself was a young man, my inclinations at first led me, like many another, into public life, and there I encountered many obstacles; for instead of modesty, incorruptibility and honesty, shamelessness, bribery and rapacity held sway. And although my soul, a stranger to evil ways, recoiled from such faults, yet amid so many vices my youthful weakness was led astray and held captive my ambition; for while I of took no part in the evil practices of the others, yet the desire for preferment made me the victim of the same ill-repute and jealousy as they.

Translation by John C. Rolfe (1931).

Want More Sallust and More Bellum Catilinae?

Daniel made two video’s in Latin where he goes through the part of Bellum Catilinae where Catiline was defeated. You can find them here along with the Latin text and an English translation.

If you want to read and/or listen to the entire book, you can find it both as a Read-Along (i.e. text with audio) and an Audiobook in our Latin app called Legentibus. You can learn more about it here. There is a 3 day free trial is you want to give it a go.