Contents

Two thousand years of Latin Prose is a digital anthology of Latin Prose. Here you will be able to find texts from two millennia of gems in Latin. In this third chapter, we will learn about, and read part of a speech from, Gaius Gracchus as found in Aulus Gellius XI.10.2–6.

If you want to learn more about the anthology, you will find the preface here.

Life & Works of Gaius Gracchus

In this section you will learn about the author’s life and works.

(154–121 B.C.)

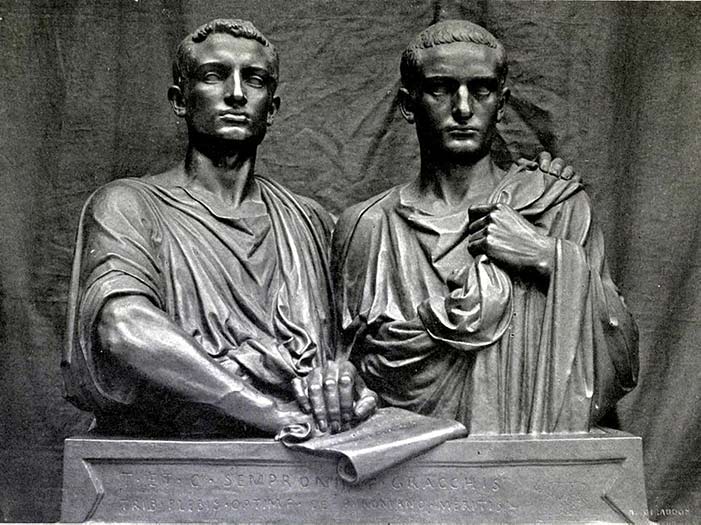

Gaius Gracchus is perhaps most famous for his tragic end which strongly echoed that of his older brother, Tiberius Gracchus. Gaius Gracchus was, just as his brother had been, a very strong orator, renowned for his elegant and pure Latin.

Life of Gracchus

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus was born in 154 B.C. to consul Tiberius Gracchus and Cornelia Africana.

His mother Cornelia was, or rather is, one of the most famous Roman women. She was the daughter of the great Roman general Scipio Africanus (the one who defeated Hannibal) and she became the ideal of how a Roman woman should be. Tiberius Gracchus was much older than her, but they had twelve children together out of which only three survived childhood: Tiberius Gracchus Minor, Gaius, and Sempronia.

When Cornelia was widowed she raised her children alone. She has been given praise throughout history for the education she provided for her children, and for her knowledge and prudence. Cicero was very impressed by her and praised her for making sure her sons learned Greek properly, for instance, she made sure that one of their teachers was Diophanes of Mytilene, who was one of the most famous contemporary speakers (Cicero, Brutus, 2.11). So involved was she with her children, which was contrary to all aristocratic practice at the time (Brutus, 2.11), that when the Egyptian king, Ptolemy VIII, proposed to her, she turned him down—at least so we’re told by historian Plutarchos, known in English as Plutarch (46–120 A.D.) (Tiberius Gracchus, 1).

This thorough education ensured by his mother gave Gaius, just as it gave his older brother Tiberius, a great ground to stand upon in the political arena of Rome. They had practiced Greek rhetorical techniques and been drilled by their mother in finding simple and precise expressions. This turned them both into skilled orators.

Tiberius Minor was nine years older than Gracchus and became a tribune of the plebs. He became famous and infamous for his many reforms to help the poor. He, for instance, wanted to transfer land from wealthy Romans to poorer citizens—a reform popular amongst the poor but not by the wealthy. He was killed by an angry senatorial mob.

The death of his brother hit Gaius hard. He was not even allowed to bury him, as his body was thrown into the Tiber. So, he stepped back from politics and his career and kept quiet for a while. But, as his friend Vettius was under prosecution, he came back into the public light to defend him. And this was only the beginning.

In 126 B.C. he became quaestor in Sardinia, where he earned himself a good reputation, and then, in 123 B.C., he became tribune of the plebs, the same office that his brother had held. However, Gaius’ reforms were even greater than his brother’s had been. He revived the land reform program his brother had instigated, he initiated tax reforms, military reforms, as well as making sure the state would buy bulk grain to distribute to poorer citizens at a low price – the so-called Lex Frumentaria.

Gracchus’ reforms and popularity with the people brought him a lot of enemies, especially with the senate. So, when the decision was made to found a colony by the recently destroyed Carthage, Gaius was appointed to oversee the construction together with one of his allies, Fulvius Flaccus. They were therefore sent to Africa.

In 121 B.C., upon their return to Rome, the political climate had changed, erupting in riots and violence. The two men and their followers met with a situation so dangerous that the only option was to flee the city. They failed. Flaccus was killed by a mob. Gaius managed to get to the other side of the Tiber, where the seriousness of the situation caught up with him, and he decided to take his own life with the help of his slave Philocrates.

3000 of Gaius’ supporters were also killed and thrown into the Tiber, their properties confiscated and their wives forbidden to mourn.

According to Greek-Roman historian Appianus, or Appian (95–165 A.D.), the heads of Flaccus and Gaius were carried to Lucius Opimius, consul and sworn enemy of Gaius and his supporters—who later repealed all of his laws and reforms, save Lex Frumentaria. Opimius gave their weight in gold to those who had brought heads. (Appianus, Civil Wars, 1.26) Plutarch also mentions this incident but adds that the one who brought Gaius’ head tried to cheat and filled it with molted led to make it heavier and that those who brought Flaccus’ head were of such an obscure sort that they got nothing from Opimius. (Gaius Gracchus, 17)

Works of Gracchus

As mentioned earlier, Gaius was famous for his pure and elegant Latin, owing to his mother’s thorough education and his Greek teachers. He mixed an eloquent Latin with Greek speaking techniques with a passion for what he spoke about.

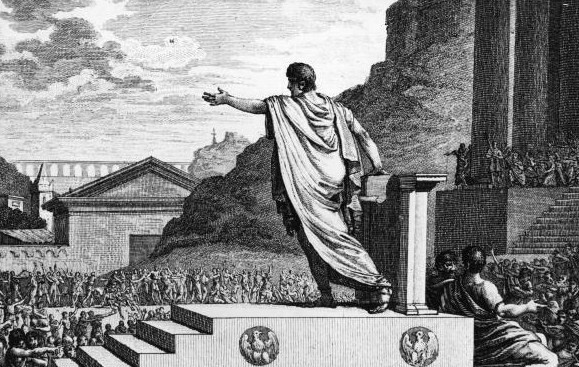

According to Plutarch, Gaius’ speech was awe-inspiring and passionate, but he had a temper and was supposedly often carried away by it. So, when his voice was raised too high due to the heat of the moment, a servant – Licinius – who always stood behind him when he spoke, sounded a soft key with a pitch pipe so that Gaius would remember to take his voice back down. (Plutarchos, Tiberius Gracchus, 2)

So famous was Gaius Gracchus for his rhetoric elegance that the Roman rhetorical treatise, called Rhetorica Ad Herennium, draws a substantial part of its examples from him.

“Quid? ipsa auctoritas antiquorum non cum res probabiliores tum hominum studia ad imitandum alacriora reddit? Immo erigit omnium cupiditates et acuit industriam cum spes iniecta est posse imitando Gracci aut Crassi consequi facultatem.”

— Ad Herennium, IV, II.

And furthermore, does not the very prestige of the ancients not only lend greater authority to their doctrine but also sharpen in men the desire to imitate them? Yes, it excites the ambitions and whets the zeal of all men when the hope is implanted in them of being able by imitation to attain to the skill of a Gracchus or a Crassus.

Though Gaius Gracchus was an important orator, only a few fragments of his speeches have come done to us.

In today’s chapter of 2000 years of Latin Prose, we will take a look at a part of his speech opposing the Lex Aufeia, a Roman tax law, from 124 or 123 B.C. The passage is found in Aulus Gellius’ Noctes Atticae (2nd cent. A.D.), an eclectic work containing a myriad of extracts from Roman authors. We will return to the Noctes Atticae in the chapter about Gellius.

Further resources and reading

If you want to learn more about Gracchus and his brother and their political ideas as well as their gruesome deaths, I can recommend reading the chapters about the Gracchi brothers in Plutarch’s Lives. Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus and in Appianus’ Civil wars, liber 1. Details differ between the two historians, but they are both really good reads. Though, for those of you who, like me, do not read Greek, I recommend turning to the English translation.

If you are curious about the Lex Aufeia and dating it, there is an article from Cambridge University Press about it here: ”The So-called Lex Aufeia (Gellius xi 10)”

Audio & Video in Latin

Click below to read and listen to a passage of a speech by Gracchus.

Video with English subtitles

Audio of Latin text

Latin text

Below you will find the original text of the passage in Latin.

AP. GELL. XI.10.2–6

”Nam vōs, Quirītēs, sī velītis sapientiā atque virtūte ūtī, etsī quaeritis, nēminem nostrum inveniētis sine pretiō hūc prōdīre. Omnēs nōs, quī verba facimus, aliquid petimus, neque ūllīus reī causā quisquam ad vōs prōdit, nisi ut aliquid auferat.

Ego ipse, quī aput vōs verba faciō utī vectīgālia vestra augeātis, quō facilius vestra commoda et rem pūblicam administrāre possītis, nōn grātīs prōdeō; vērum petō ā vōbīs nōn pecūniam, sed bonam exīstimātiōnem atque honōrem.

Quī prōdeunt dissuāsūrī nē hanc lēgem accipiātis, petunt nōn honōrem ā vōbīs, vērum ā Nīcomēde pecūniam; quī suādent, ut accipiātis, hī quoque petunt nōn ā vōbīs bonam exīstimātiōnem, vērum ā Mithridāte reī familiārī suae pretium et praemium; quī autem ex eōdem locō atque ōrdine tacent, hī vel ācerrimī sunt; nam ab omnibus pretium accipiunt et omnīs fallunt.

Vōs, cum putātis eōs ab hīs rēbus remōtōs esse, impertītis bonam exīstimātiōnem; lēgātiōnēs autem ā rēgibus, cum putant eōs suā causā reticēre, sūmptūs atque pecūniās maximās praebent, item utī in terrā Graeciā, quō in tempore tragoedus glōriae sibi dūcēbat talentum magnum ob ūnam fābulam datum esse, homō ēloquentissimus cīvitātis suae Dēmādēs eī respondisse dīcitur: “Mīrum tibi vidētur, sī tū loquendō talentum quaesīstī? ego, ut tacērem, decem talenta ā rēge accēpī.” Item nunc istī pretia maxima ob tacendum accipiunt”.

Vocabulary and Commentary

These following words are key to understanding the text, if you already know them — great! — if not, make a mental note of them.

aput: in your presence. Aput is another form of the more common apud,

existimatio: opinion, reputation

gloriae sibi ducere: To consider praiseworthy, to boast; this is a so-called double dative, or final dative, which is a common construction in Latin, cf. Hoc mihi honori est (“This is an honour for me.”) and Hoc mihi gaudio est (“This is joyous for me”).

gratis (adv.): for free

item (adv): similarly

magnum talentum: a whole talent. A weight of precious metal or sum, which varied over time (ca. 60–70lb.).

neque ullius rei causa: (lit.) and not for any other reason. Causâ placed after a noun in the genitive expresses purpose, not cause.

ob tacendum: to be quiet

quirites: Quiritesoriginally designated the inhabitants of the Sabine town Cures (cf. Col. praef. § 19, veteres illi Sabini Quirites).After the Sabines and the Romans had united in one community, under Romulus, the name of Quirites was taken in addition to that of Romani, the Romans calling themselves, in a civil capacity, Quirites, while, in a political and military capacity, they retained the name of Romani. (Lewis & Short)

quo facilius: Final clauses with comparative adverbs, e.g. facilius, in Classical Latin are usually constructed with quo instead of ut, e.g. Latine loquuntur quo melius legant (“They speak Latin in order to read better”).

res familiaris: househould, property, possesions

reticere: keep silent (about something)

sua causa: for their (own) sake

verba facere: talk, give a speech

English Translation

Below you will find an English translation of the text.

Ap. Gell. XI. 10.2–6

“For you, fellow citizens, if you wish to be wise and honest, and if you inquire into the matter, will find that none of us comes forward here without pay. All of us who address you are after something, and no one appears before you for any purpose except to carry something away.

I myself, who am now recommending you to increase your taxes, in order that you may the more easily serve your own advantage and administer the government, do not come here for nothing; but I ask of you, not money, but honour and your good opinion.

Those who come forward to persuade you not to accept this law, do not seek honour from you, but money from Nicomedes; those also who advise you to accept it are not seeking a good opinion from you, but from Mithridates a reward and an increase of their possessions; those, however, of the same rank and order who are silent are your very bitterest enemies, since they take money from all and are false to all.

You, thinking that they are innocent of such conduct, give them your esteem; but the embassies from the kings, thinking it is for their sake that they are silent, give them great gifts and rewards. So in the land of Greece, when a Greek tragic actor boasted that he had received a whole talent for one play, Demades, the most eloquent man of his country, is said to have replied to him: ‘Does it seem strange to you that you have gained a talent by speaking? I was paid ten talents by the king for holding my tongue.’ Just so, these men now receive a very high price for holding their tongues.”

Translated by J.C. Rolfe (1927).