Contents

Two thousand years of Latin Prose is a digital anthology of Latin Prose. Here you will be able to find texts from two millennia of gems in Latin. In this seventh chapter, we will learn about the pseudo-Caesarian work written in the style of Julius Caesar’s De Bello Gallico and De Bello Civile, called Bellum Alexandrinum or De Bello Alexandrino. We will read a passage throwing us straight into the war between Caesar’s men and the Alexandrians.

If you want to learn more about the anthology, you will find the preface here.

Bellum Alexandrinum

(c. 47–43 B.C.)

Bellum Alexandrinum, De Bello Alexandrino, or in English The Alexandrine War is a work much like Julius Caesar’s De Bello Gallico and De Bello Civile that we spoke of in the previous chapter of 2000 years of Latin Prose.

Bellum Alexandrinum is named after Caesar’s campaign in Alexandria and Lower Egypt and contains events and campaigns after this. The work takes the reader through from September 48 B.C. to August 47 B.C., meaning we get to visit Alexandria and Illyria, Spain, and modern Turkey.

The work belongs to the so-called Corpus Caesarianum, i.e., a collection of texts consisting of the two books by Julius Caesar mentioned above, as well as the eighth book of De Bello Gallico (which was not written by Caesar), Bellum Africanum, and Bellum Hispaniense. All of these works within the Corpus Caesarianum are commentaries relating Caesar’s war campaigns and are written in the same spirit. However, only De Bello Gallico lib. 1–7 and De Bello Civili are genuinely written by Julius Caesar. The others are so-called pseudo-Caesarian works but are, since medieval times, regularly bound with Caesar’s authentic works.

But if Julius Caesar did not write the Bellum Alexandrinum, who did?

The simple answer is this: we do not know.

The authorship of Bellum Alexandrinum, as well as Bellum Africanum and Bellum Hispaniense, has been debated for centuries. It is possible that contemporaries to the works knew, but even in antiquity, the authorship of the works was discussed.

Suetonius wrote:

“Nam Alexandrini Africique et Hispaniensis incertus auctor est; alii Oppium putant, alii Hirtium, qui etiam Gallici belli novissimum imperfectumque librum suppleverit.”

— Suetonius, Divus Julius, I.56

“for the author of the Alexandrian, African, and Spanish Wars is unknown; some think it was Oppius, others Hirtius, who also supplied the final book of the Gallic War, which Caesar left unwritten.”

Was Gaius Oppius the Author of Bellum Alexandrinum?

Suetonius mentioned a certain Oppius to be a possible author of the Alexandrine War, but who was he?

Gaius Oppius was a close friend of Julius Caesar. We don’t know much about him, not when he was born, not when he died. We do know that he managed Caesar’s personal affairs in Rome when Caesar was absent. He supposedly wrote about the life of Caesar, the elder Scipio Africanus and Marius, as well as a pamphlet trying to prove that Cleopatra’s son, Caesarion, was not fathered by Caesar. (ref. Cic. Ad Q. Fr. 3.1.8, Gell. 17.9.1, Plutarch Caes. 15–17, Suet. Jul. 52.3)

Suetonius mentioned him not only as the author of the Alexandrine War but the African and Spanish Wars too. This idea has been discarded, and most scholars have even shot down the claim of him having authored the Alexandrine War.

Did Aulus Hirtius Write Bellum Alexandrinum?

Suetonius also mentions a “Hirtius”. The man he refers to was a man named Aulus Hirtius (c. 90–43 B.C.) who was a consul and also a legate of Julius Caesar from about 58 B.C.

After Caesar’s death, Hirtius initially sided with Mark Anthony, however, as Cicero was a close friend of his Hirtius was persuaded to switch sides. This side-change is also what killed him as he set out with an army to attack Anthony only to fall in battle. The correspondence between Cicero and Hirtius was published (in nine books) but has not survived history.

Hirtius is believed to have written the eighth book of the otherwise Caesar-authentic De Bello Gallico. This is one of the main reasons why Hirtius has been the front runner of possible authors to Bellum Alexandrinum. However, scholars are still not sure due to details within the text, as well as for linguistic and stylistic reasons. For instance: Parts of the Bellum Alexandrinum clearly shows that the author was an eyewitness. However, Hirtius himself states that he was not present in Alexandria at the time. And, the style of the language changes character mid-work.

Nevertheless, Hirtius could have written the work relying eyewitness reports.

Today, many believe that Hirtius was the editor of the text, that he forged together reports written by others during the war for submission to Caesar, perhaps even at the request of Caesar. He might also have edited Bellum Africanum and Bellum Hispaniense, though today scholars are sure they were not written by the same author/authors as Bellum Alexandrinum.

Most likely, we shall never know who wrote the book, just as we will never know exactly when it was written.

If it was written or edited by Hirtius, it must have been before his death in 43 B.C. The work itself deals with events during 48–47 B.C. And, it seems to be the consensus that the work was written shortly after the events of the campaigns described within the text.

Julius Caesar’s War With Alexandria

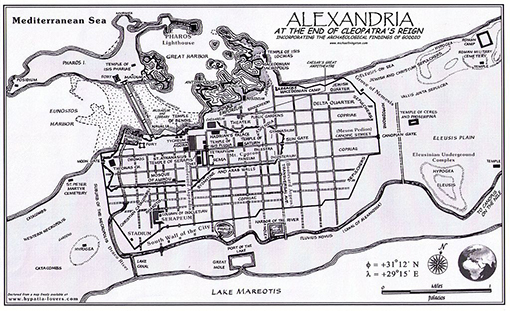

In today’s chapter of 2000 years of Latin Prose, we shall read a passage that takes place mid-Alexandrian-war. We will be thrown into action as Caesar’s men fight the Alexandrians on the so-called “mole”, also known as the Heptastadion.

The mole was a long causeway that led from the mainland and city of Alexandria over to Pharos Island. It had two channels with bridges across, to connect the harbours.

At the stage in the war that we will be reading about, Julius Caesar had just posted a garrison at the bridge closest to Pharos Island while the other one, closest to the mainland was held by the Alexandrinians.

But, let us first take a step back and briefly take a look at the reason for the war and go through a few details from the war itself:

First and foremost: Egypt was an important trade partner to Rome, especially when it came to grain, and any disturbances to the trade could have disastrous consequences for Roman citizens. Hence Egyptian politics was rather important to the Romans.

Read on.

It all began when the Pharaoh Ptolemaios (Ptolemy) XII Auletes sought the help of the triumvirs Julius Caesar, Pompeius Magnus (Pompey), and Marcus Licinius Crassus to be reinstated after having been expelled. They supported him and made his case in the Senate. Ptolemy even stayed in Pompey’s house during his exile from Egypt. Ptolemy was reinstated but died in 51 B.C. without having paid back his debts to Roman creditors (he had borrowed a lot of money to use for bribes).

Ptolemy gave his throne to his oldest son, also called Ptolemy, and his oldest daughter to share – that would be the famous Cleopatra. He made the people of Rome executor of his will in order to secure his heir’s hold on the Egyptian throne and to ensure that his wish about the split regency was observed after his death.

It was not.

Cleopatra was driven out by her brother. Thus, she went to Syria and raised an army.

Meanwhile, back in Rome Pompey and Caesar were busy with the civil war. Pompey fled to Egypt only to be killed on sight by former soldiers from his own army at the proposition of Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII’s advisors (that would be Cleopatra’s brother).

This did not sit well with Caesar who despite waging war with Pompey, still cared for him having been former friends, allies, and related (through marriage). Caesar mourned his old friend and then decided that it was time that the money Ptolemy’s father Ptolemy had borrowed was paid back to Rome. He also decided to settle the dispute between Ptolemy and Cleopatra.

Caesar famously sided with Cleopatra.

In the end, Ptolemy drowned in the River Nile, passing the “pharaohship” to his younger brother – also named Ptolemy – and his sister Cleopatra was reinstated as his co-ruler.

Further reading and resources

Why not read, if you haven’t already, the previous chapter in the Anthology about Julius Caesar.

Otherwise, I can highly recommend reading The cambridge companion to the writings of Julius Caesar, ed. Luca Grillo, Christopher B Krebs (2017) that not only discuss Caesar’s texts but the pseudo-Caesarian writings as well.

Also interesting are the following articles:

- ”Hirtius and the Bellum Alexandrinum” Lindsay G.H. Hall, The classical Quqarterly vol 46, no 2 (1996) pp 411–415.

- ”The text history of the Corpus Caesarianum”, Charles H. Beeson, Classical Philology, vol 35. No 2 (1940) pp 113–125

If you want to learn more about the language, style and narrative technique in the Alexandrine War:

- ”Caesar and the Bellum Alexandrinum: An Analysis of Style, Narrative technique and the reception of Greek Historigraphy” Jan Felix Gaertner, Bianca C. Hausburg. (2013)

Audio & Video in Latin

Click below to read and listen to a passage from Bellum Alexandrinum.

Video with English subtitles

Audio of Latin text

Latin text

Below you will find the original text of the passage in Latin.

Bellum Alexandrinum, 20

In his rebus occupato Caesare militesque hortante remigum magnus numerus et classiariorum ex longis navibus nostris in molem se eiecit. Pars eorum studio spectandi ferebatur, pars etiam cupiditate pugnandi. Hi primum navigia hostium lapidibus ac fundis a mole repellebant ac multum proficere multitudine telorum videbantur. Sed postquam ultra eum locum ab latere eorum aperto ausi sunt egredi ex navibus Alexandrini pauci, ut sine signis certisque ordinibus, sine ratione prodierant, sic temere in navis refugere coeperunt. Quorum fuga incitati Alexandrini plures ex navibus egrediebantur nostrosque acrius perturbatos insequebantur. Simul qui in navibus longis remanserant scalas rapere navisque a terra repellere properabant, ne hostes navibus potirentur. Quibus omnibus rebus perturbati milites nostri cohortium trium quae in ponte ac prima mole constiterant, cum post se clamorem exaudirent, fugam suorum viderent, magnam vim telorum adversi sustinerent, veriti ne ab tergo circumvenirentur et discessu navium omnino reditu intercluderentur munitionem in ponte institutam reliquerunt et magno cursu incitati ad navis contenderunt. Quorum pars proximas nacta navis multitudine hominum atque onere depressa est, pars resistens et dubitans quid esset capiendum consili ab Alexandrinis interfecta est; non nulli feliciore exitu expeditas ad ancoram navis consecuti incolumes discesserunt, pauci allevatis scutis et animo ad conandum nisi ad proxima navigia adnatarunt.

Vocabulary & Commentary

These following words are key to understanding the text, if you already know them — great! — if not, make a mental note of them.

remex, ‑igis, m.a rower, oarsman

classiarius, ‑i, m. a marine

temere adv. rashly

ut…sic: (comparatively) as…so

potior, ‑itus sum, ‑iri dep. (regularly with abl.) to take possession of

magnam vim: a large number of

quorum pars: Releative pronouns are commonly used to refer backwards like this: “some (a part) of them (i.e.) Romans”.

proximas nacta navis: having reached the nearest ships. Note. nacta is nominative singular of the perfect participle of the verb nanciscor (“to reach”). Since the verb is deponent, the perfect participle is active. Nāvīs is the accusative plural here.

nīsī: nominative plural of perfect participle of nitor to rely on, strive

allevatis scutis: ablative absolute “having/with the shields lifted up”

English translations

Below you will find an English translation of the text.

The Alexandrian war

While Caesar was occupied with this situation, and as he was encouraging the troops, a large number of rowers and seamen left our warships and suddenly landed on the mole. Some were inspired by their anxiety to watch the fray, others also by the desire to take part in it. They began by driving back the enemy vessels from the mole with stones and slings, and it seemed that their heavy volleys of missiles were having great effect. But when a few Alexandrians ventured to disembark beyond that point, on the side of their unprotected flank, then, just as they had advanced in no set order or formation and without any particular tactics, so now they began to retire haphazardly to the ships. Encouraged by their retreat, more of the Alexandrians disembarked and pursued our flustered men more hotly. At the same time those who had stayed aboard the warships made haste to seize the gang-planks and ease the ships away from land, to prevent the enemy from gaining possession of them. All this thoroughly alarmed our troops of the three cohorts which had taken post on the bridge and the tip of the mole; and as they heard the clamour behind them, and saw the retreat of their comrades, and sustained a heavy frontal barrage of missiles, they feared they might be surrounded in rear and have their retreat entirely cut off by the departure of their ships; and so they abandoned the entrenchment they had begun at the bridge, and doubled frantically to the ships. Some of them gained the nearest ships, only to be capsized by the weight of so many men; some were killed by the Alexandrians as they put up a forlorn and bewildered resistance; some proved luckier in reaching ships at anchor cleared for action, and so got away safely; and a few, holding their shields above them and steeling their resolution to the task, swam off to ships near by.