Guest post written by Eleanor Dickey, Professor of Classics at the University of Reading in England.

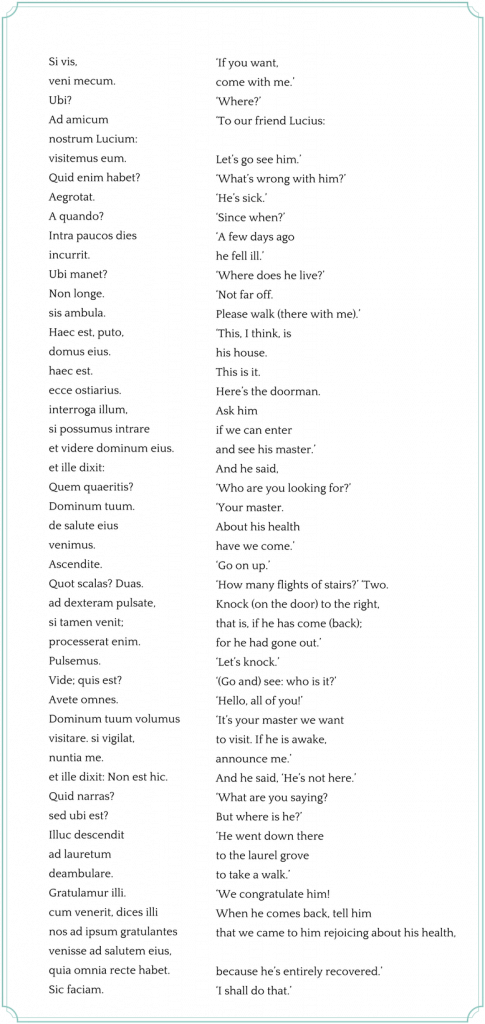

Two thousand years ago, when the Romans ruled a vast empire whose inhabitants spoke all sorts of different languages, many of those inhabitants wanted to learn Latin. So they signed up for Latin classes, where they learned using textbooks containing little dialogues about everyday life. These dialogues are in some ways remarkably similar to texts used today to teach modern foreign languages, introducing learners to Roman culture along with Latin: they illustrate how to use the public baths, the banks, the markets, the temples, the law courts, etc. Here is one about visiting an ailing friend:

The two-column format of this text is original, though the translation was originally into Ancient Greek rather than into English. For unlike their modern counterparts, the ancient learners’ dialogues are all bilingual, with a running translation in the students’ native language. The translation matches the original line for line, so that the learner can understand exactly how the original means what it means. This works better with Ancient Greek than it does with English, because of the fixed word order of English, but I’ve managed to keep the line-for-line format in all but two lines of the passage above.

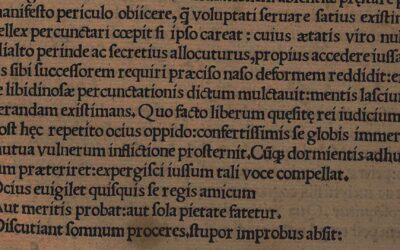

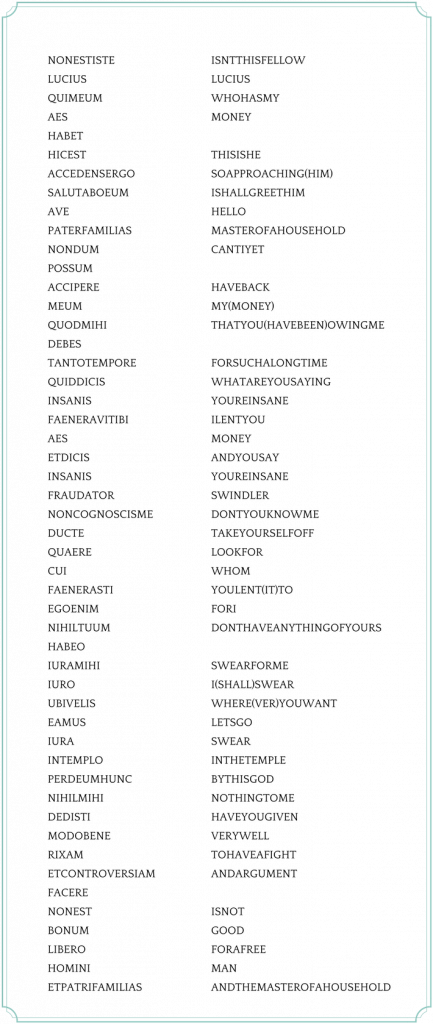

The reason learners needed bilingual texts was that in antiquity writers did not leave spaces between words; they also did not normally use punctuation or capitalization. It is not too difficult to read one’s own language in that format, but reading a foreign language is really tough, since if you don’t know where the words begin and end, you cannot use a dictionary. And without a dictionary you have no hope at all with a monolingual text.

The extract below is written with both the Latin and the English in the ancient format: can you work out what it says? (Hint: the dialogue is about someone who claims another person owes him money; as in the previous passage quoted, parentheses indicate words in the English that are not actually present in the Latin.)

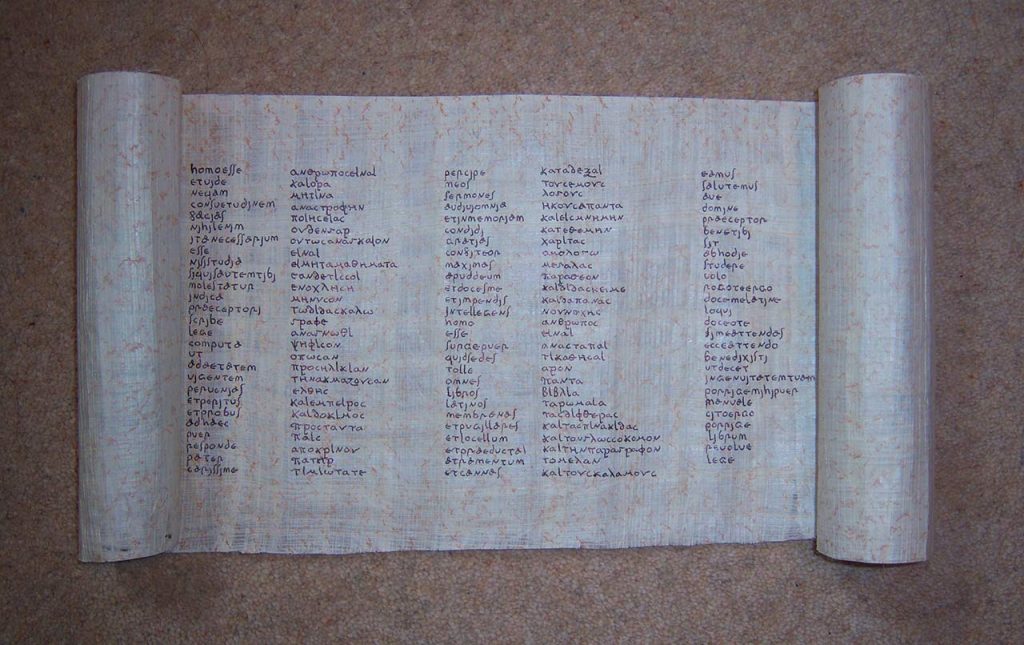

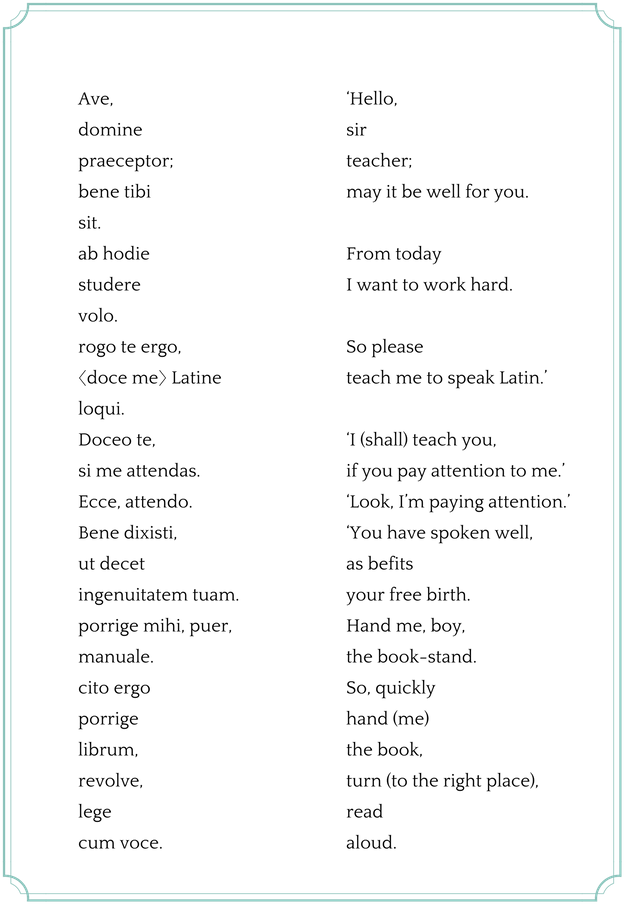

Among the dialogues are many about going to school, such as this one:

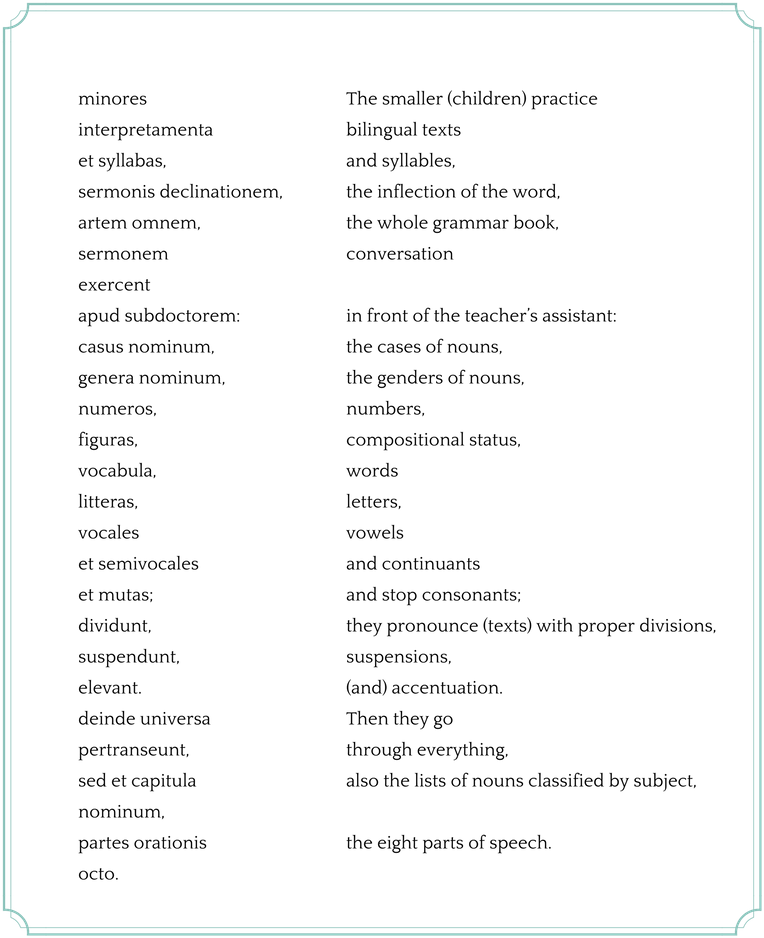

These school dialogues are particularly valuable for people today who would like to know exactly how ancient students learned languages. In the extract above, for example, the boy’s first exercise is reading aloud, a task that was extremely challenging without word division or punctuation. In the extract below, we see language learners tackling an impressive amount of grammar:

Ancient Latin learners, in fact, did most of the things modern Latin learners do. In addition to learning grammar, they translated Latin texts into their own language, and texts into their own language into Latin. They read Virgil’s Aeneid (though usually they didn’t get very far) and Cicero’s Catilinarian Orations. When they had gained enough vocabulary to be able to cope without a running Latin translation, they read monolingual Latin texts, using dictionaries and commentaries to decipher them and writing translations of the hard words into their copies of the text. And, like many modern learners, some ancient learners eventually became very good at the language and went on to read texts without needing to look up the hard words and write them down.

The book Learning Latin the Ancient Way explains more about how ancient students learned Latin, Stories of Daily Life from the Roman World provides translations of all the ancient Latin-learning dialogues, and Reading ancient schoolroom offers a modern reconstruction of ancient Latin classes.