Written by Hans Aili, Professor emeritus of Latin, Stockholm University.

Possessing a compendious knowledge of the physical world was easier in the old days than it is today. Not so very long ago, all human knowledge could be housed within the brain of one single human being. All this knowledge, moreover, was expressed in one single language.

It is true that a great deal of this ancient fund of knowledge has since been proved faulty and that we have nowadays progressed much further along the path of science. This does not change the simple fact that Science possessed this single, all-embracing language capable of expressing everything, in prose as well as in poetry, and that all budding scientists learned this language from first grade at school, read it, wrote in it, gaining familiarity and fluency until they could use it in conversation and correspondence with all the others who had progressed along the same road – and that meant every man and woman of culture and learning from the whole of Europe and most of the world, irrespective of their nationality – German, Italian, Frenchman, Englishman, Scot or Swede (and many others).

This language was Latin, which, besides its own vocabulary, possessed a rich hoard of words, culled from the Greek and transformed to fit their new environment.

A statement like this is true but restricted by one important factor: Latin was a language of writing and literature. When spoken and heard, it offered unexpected pitfalls. When the Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus, visited England in the middle of the 1730s, he met and conversed with Sir Hans Sloane and other illuminaries of the Royal Society, but complained afterwards that Sir Hans did not know Latin. Linnaeus, for his part, had no English. His reaction was almost certainly wrong – it is not very likely that Sloane’s Latin was deficient. The real problem probably was that Latin is pronounced in one way in England and in quite a different way in Sweden. Every modern nation has its own rules for pronouncing Latin, and when we speak Latin, each according to our own national rules, we find everybody else impossible to understand, at the best, or incredibly funny, at the worst. And they, of course, think the same about us!

Linnaeus, however, lived during a period that straddled a great dividing line in time: after the year 1750 the vernacular languages (English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish, and all others) started an irrevocable process whereby they took over as the languages of Science and Learning. The medical profession resisted longest – it is easy to find dissertations in Medicine, written in Latin, and dating from the middle of the 1800s. For the medical profession, it was very important to possess one, single, well-developed and shared language, and to give up this possession and receive four or five still not fully developed languages in its place was no very great improvement. But progress moves forwards, as we say, and after a short bout in the 1950s, when Latin without Inflections, generally called Interlingua, was tried out as a language of conferences, English stepped in to take over as the international language of Science.

But we are still facing the fact that a very large proportion of the works of Science and Medicine published before 1750 were written in Latin. Anyone wishing to study the history of Science will find that year to be a linguistic dividing line, an iron curtain that only determined studies in Latin will help you to raise. We may add another complication: the scientists of that time wrote a Latin that had been developed and brought to perfection in the last century before Christ. The names of these creative innovators and literary geniuses are, Caesar, Cicero, Vergil, Horace, Livy, and many others. They did not write about science but about war, they made speeches on politics and legal matters, wrote learned tomes on history and poetry about Love or the greatness of Rome. The scientists of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries imitated their language, to the best of their ability, but added new words and new thoughts. They still loved and imitated the complicated grammar and brilliant style of the ancients, and this combined imitation and innovation makes modern Latin of Science both difficult and charming.

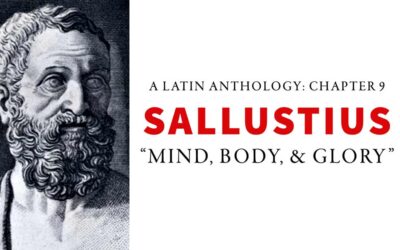

It is easy to illustrate this. Maps offer excellent examples. The geographers of the early modern world found the shape of the planet Earth an intriguing subject for study, and they formed many conflicting theories. Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598) was a Flemish cartographer who produced a line of maps of the world, among which we note one that he called Typus orbis terrarum (Image of the World):

This map represents his theory on the shapes of the continents and the names and locations of oceans, land masses, rivers, and towns. Its captions form a mixture of different languages: the large formations have Latin names, smaller items bear names given by the explorers, who were mostly Spanish and Portuguese. Aditionally, he offers more specific information, and this is always in Latin. He recognises his debt to the ancient masters by adding at the bottom a quote from one of them:

Quid ei potest videri magnum in rebus humanis, cui aeternitas omnis totiusque mundi nota sit magnitudo (”What, among things human, might appear large to one who knows the whole of eternity and the size of the whole world”), a bon mot by Cicero, Tusculanae disputationes 4,37 – Ortelius is not word perfect but the sense is the same as Cicero’s; I use a Latin spelling that is normal today).

In the middle of the American continent Ortelieus puts a note: AMERICA SIVE INDIA NOVA. Anno 1492 a Christophoro Colombo nomine regis Castellae primum detecta (America, or New India. First discovered in the year 1492 by Christopher Columbus in the name of the King of Castilia).

One geographical point, still undecided at that time, is noted: Nova Guinea nuper inventa, quae an sit insula an pars continentis Australis incertum est (New Guinea, recently discovered; whether this is an island or a part of the Southern continent is not certain). Along the length of this entire continent he comments: Terra Australis nondum cognita (The Southern Land, not yet known).

A question of name is introduced: Hanc continentem Australem, nonnulli Magellanicam regionem ab eius inventore nuncupant (This Southern continent is called by some, The Magellan Region, after its discoverer).

He also offers a zoological observation on animals in the Antarctic: Psittacorum regio, sic a Lusitanis appellata ob incredibile earum avium ibidem magnitudinem (The region of the Parrots, thus named by the Portuguese because of the incredible size of these birds there).

At the extreme right-hand lower corner the continent bordering on the South Pole is awarded a comment: Vastissimas hic esse regiones ex M. Pauli Veneti et Lud. Vartomanni scriptis peregrinationibus constat (That these lands are enormously large is known thanks to the wanderings of Marco Polo of Venice and Lodovico de Varthemas).

These pieces of information are, perhaps, not so very deep, but rather charming – not least the fact that the Portuguese considered the penguins to be variants of the parrots. But unless you know Latin, this information will escape your attention entirely.

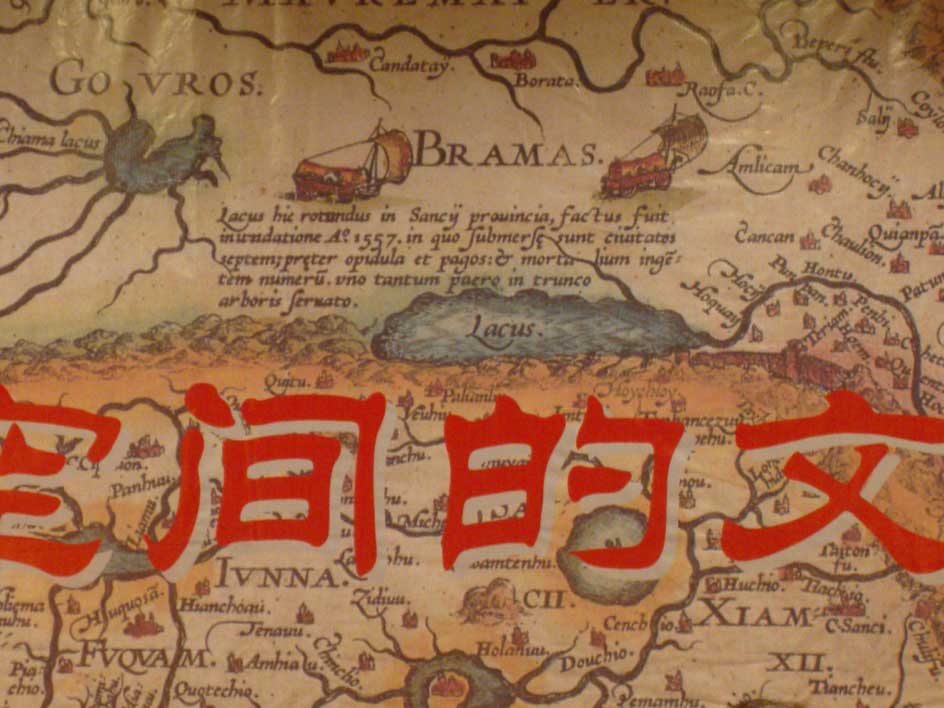

A personal note might be of interest here: my interest in Latin as a source language for the history of Science was aroused by the request of a colleague, who had no Latin, but wished me to take a look at two 17th century academic treatises published at the University of Uppsala, Sweden: Jonas Locnaeus, Murus Sinensis (The Chinese Wall) of 1694 and Eric Roland, De magno Sinarum imperio (On the Great Empire of the Chinese) of 1697. I was awarded the chance of presenting this work at two conferences held at Fudan University of Shanghai. The theme of the second conference, held in 2008, was The History of Geography. The organisers, wishing to illustrate the historical and international aspect of this subject had taken an old map of South-East Asia and reproduced it in two ways, as a backdrop to the panel and as a decoration on the tote bags given to the participants. The map is drawn in a fashion that puts North pointing to the left, and the East pointing upwards.

Just as Ortelius’s map, this one offers us names of geographical features and points of interest , all in Latin.

One small notice interested me particularly. It tells the history of a lake, somewhere on the border between Burma and Siam. It appears on the close-up picture above:

Lacus hic rotundus in Sancij provincia, factus fuit inundatione Anno 1557, in qua submersae sunt civitates septem, praeter oppidula et pagos, et mortalium ingentem numerum uno tantum puero in trunco arboris servato (This round lake in the province of Guanxi was created by an inundation in the year 1557, and there seven cities were drowned besides towns and villages, including an enormous number of humans, the one single survivor being a boy riding on a tree-trunk).

The participants were Chinese almost to a man, and none of them had any Latin. Interpreting this map without this knowledge must have been very frustrating…

To conclude – being able to read Latin will help you diffuse the fog that started to separate the scientists of the late 18th century from those of the 17th century and earlier.

You do not require a perfect knowledge of the Latin word endings and the rules of Latin syntax in order to enjoy the meaning of its vocabulary. This is particularly true when it comes to the Latin used by the medical profession. They sometimes use single words to cover up uncomfortable statements: ”The prognosis is infaust” – a phrase I observed in a handbook of the 1930s – means that the patient’s family might as well order a coffin at once. This usage of Latin, as the secret language of a professional group, was well established even in the Middle Ages, when priests could talk to each other on things like the problems of faith and dogma or sex, that they thought too sensitive for laymen.

The medical profession has, indeed, a great respect for Latinists, seeing that their entire vocabulary of technical terms is built on this foundation. But Medical Latin is in reality two languages: the words naming body parts and organs (Anatomy) is in Latin, those naming diseases (Pathology) are in origin Greek words that have been given a Latin spelling.

In Classical Antiquity, the medical men knew and named a lot of human organs, but these were mainly those you can see without dissecting a body. These well-known organs had everyday names of very ancient origins, such as caput (head), auris (ear), nasus (nose), os (mouth). When anatomists started opening up the human body, they found lots of new things to name. In order to facilitate learning, they adopted a technique of equating the organ they saw with things they knew from nature. Looking at an arm (or opening up an arm) they saw, for instance, things that looked like little mice, writhing under the skin, and called them musculus (little mouse); opening the skull, they saw features looking like the furrows of a plough, calling them sulcus; an opening that looked like a drill hole was a foramen. These names are thus metaphors and describe by comparison instead of just pointing out with an individual name (deictic words).

The Latin used by scientists and medical people is best described by a metaphor: it is a high wall hiding a secret garden. Unless scientists have studied Latin, they have no good way of looking into this enchanted world, for surprisingly few of the central scientific works have been translated into the vernacular. William Harvey (1578–1657) in 1653 published a work entitled Guilielmi Harveii Exercitationes anatomicae de motu cordis et sanguinis circulatione (William Harvey’s Anatomical Treatise on the Movement of the Heart and the Circulation of Blood). It offers proof, for the first time, that the blood does, indeed, circulate in the body, having been set in motion by the heart. It was translated into English only in 1957!

The Latinists, having learnt to climb the wall hiding this enchanted garden, are in the opposite position: they are able to look into the garden but are surprisingly indifferent to the wonders contained therein.

This is a situation that merits a new way of thinking!