Contents

Guest post written by Benjamin Turner, M.D.

I am grateful to Justin Slocum Bailey for the breath of fresh air he lets into the muggy basement of Latin instruction done The Usual Way. I wish I had come across his insights into indwelling language learning a good twenty years ago. And yet in a way, I did. It recently dawned on me that I’ve grown up from my earliest memories in an environment of living Latin: the Catholic Church.

Much has been written about the crucial importance of the Latin language for the life of prayer in the Church. The Council of Trent anathematized the suggestion that the Mass ought to be said only in the vernacular. [1] Pope John XXIII called for the replacement of university professors without Latin by those fluent in it.[2] Vatican II insisted on the retention of Latin[3], and every Pope since, including Francis, has spoken in its favour [4], [5], [6], [7]. J.R.R. Tolkien famously continued, rather loudly, to use the Latin responses at Mass after his parish had adopted the new English options.

On the other hand, I have yet to stumble across a discussion of the reverse, namely the utility of Latin prayer for the learning of the language. The reason for this is simple: Anyone who prays takes prayer as an end in itself. With the exception of the occasional prayer of petition, prayer is meant to raise the mind and heart to God, and not to get something else. Unless stated very carefully, any expression of the ‘utility’ of prayer strikes pious ears as something approaching sacrilege. For the same reason, no one who does not already pray is likely to start praying only to enhance his Latin!

So why write this essay? Easy: a great good can be accompanied by lesser ones. Food, for example, is for staying alive, but it can also provide delight and friendship. While prayer is not FOR teaching you Latin, that’s no reason it can’t do so. I hope that what follows will appeal to those who pray already, but need convincing that Latin is worth the trouble, and also to those who do not pray at all, but who would find the concept interesting for linguistic reasons. I’ll consider the essay a success if one such person pops into a church to experience Catholic prayer in its traditional form, ever ancient, ever new. I dare even hope some might discover a far greater treasure than they were looking for.

What is Latin Prayer?

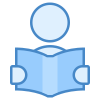

The Latin habit of prayer is impossible to define precisely, because the time allotted to prayer differs so much between people. For many, Latin prayer will be limited to the weekly Mass. At the opposite extreme, traditionally-minded monks such as those at Norcia in Italy, Le Barroux in France, or Clear Creek in Oklahoma, rise before dawn to spend half their waking hours praying in Latin. They sing roughly the whole 150 psalms in a week, besides daily Masses, private prayer, and blessings of fields, meals, beer, trucks, and pretty well omnia quae moventur in terra. For one example of something in the middle, my own habit (well, when I’m behaving myself) includes:

- Weekly Mass, with Gregorian chant whenever possible. About an hour.

- Daily Prime (morning prayer) and Vespers (evening). About fifteen minutes each.

- Daily reading of the Regula Sancti Benedicti, about five minutes.

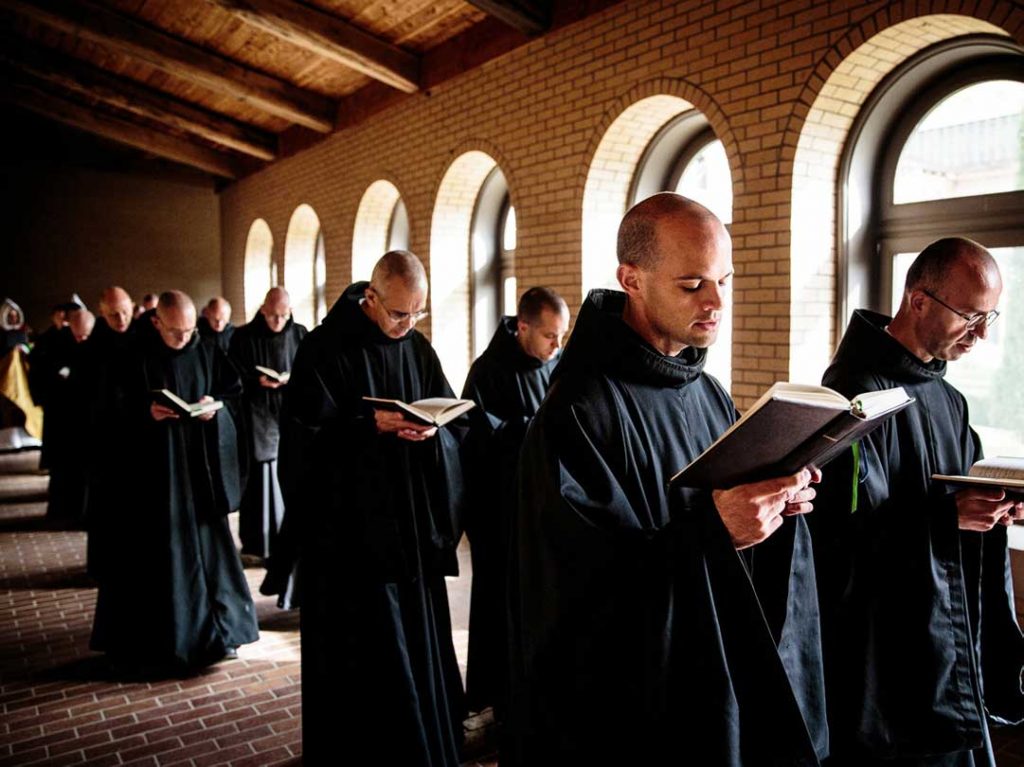

- Grace at meals, a few minutes.

- Reading of religious books in Latin, time variable.

Discipline

How does such a habit help one to learn Latin? Perhaps the most important benefit is that of discipline. All students are familiar with waxing and waning interest in their chosen fields. But when study is only a side benefit of a greater good, one sufficient in itself to motivate repeated and diligent attention, flagging becomes less likely and less severe. Catholics are used to keeping up our prayers even when we don’t feel like it. In fact, many authors suggest that dry periods are precisely when prayer is most fruitful. As a result, we’re always immersed in at least some Latin, unintentional though it may be. I can think of any number of interests I’ve adopted with vigour, only to find they’ve gone dormant or dead within a few months. Calligraphy, photography, cookery, various musical instruments, the Irish language… But my interest and proficiency in Latin only grows.

Illustration by Concrete Objects

Immersion derives much of its benefit from the use of the language on the concrete objects and actions around the student; it has the students ask each other for salt at the dinner table. The liturgy [8] is crammed with such concrete objects and actions, often accompanied by matching prayers. While the congregation is being sprinkled with holy water, they sing: “Asperges me Domine hyssopo, et mundabor. Lavabis me, et super nivem dealbabor.” [9] As the priest begins the Mass at the lowest step of the altar, he intones the psalm “Introibo ad altare Dei.” [10] While incensing the cross and altar, he says “Dirigatur ad te, Domine, oratio mea sicut incensum in conspectu tuo.” [11]Grace before supper begins “Edent pauperes, et saturabuntur…” [12] All of this makes the earthy parts of Latin prayer very earthy indeed, and as firmly grasped as earth.

Cantare amantis est

A great deal of Latin prayer is sung. This is primarily in order to make a more beautiful offering to God and to move the soul to greater love, but it is also a powerful tool for memorization. Thomas Aquinas was a prolific theologian who discussed everything from the heart beat to the proof of God’s existence by means of natural reason. Few Catholics could quote any of that work from memory, but many could recite a few stanzas of his music for the feast of Corpus Christi, and most could hum the tunes. Some liturgical Latin music is easy, even downright pleasurable to learn. Many authors took advantage of the new popularity of rhyming text to repeat the same grammatical form for effect. For example: [13]

“Jesu, spes paenitentibus,

quam pius es petentibus,

quam bonus te quaerentibus,

sed quid invenientibus?”

— “Jesu Dulcis Memoria,” Attr. to St. Bernard of Clairvaux, d. 1153The Dies Irae from the Requiem Mass plays a similar game throughout, without becoming pedantic. Maybe that explains why it’s one of the catchiest tunes in the history of music, covered by Mozart, Haydn, Verdi, Berlioz and Liszt, and borrowed by movies from The Lion King to Star Wars. (This link is provided only for the entertaining historical discussion. The snippets of the Dies Irae itself are deplorably bad.)

Repetition and Memorization

Even a basic package of Latin prayer will see the most fundamental prayers, a few pages worth, repeated either daily or weekly. These are quickly memorized, invariably before a complete grasp of the grammar or vocabulary. The vernacular sense, or a translation, for example of the Lord’s Prayer or grace at meals, is generally known. One therefore has something like a living parallel text in the imagination. Knowing by heart what the Latin means, one learns slowly but surely why it means it. After a while, the crib fades out and one is thinking, at least for a few paragraphs, in Latin. These prayers become the center of one’s intimacy with the liturgy, the reassurance that for all its mystery, it is one’s own.

Breadth of Style and Purpose

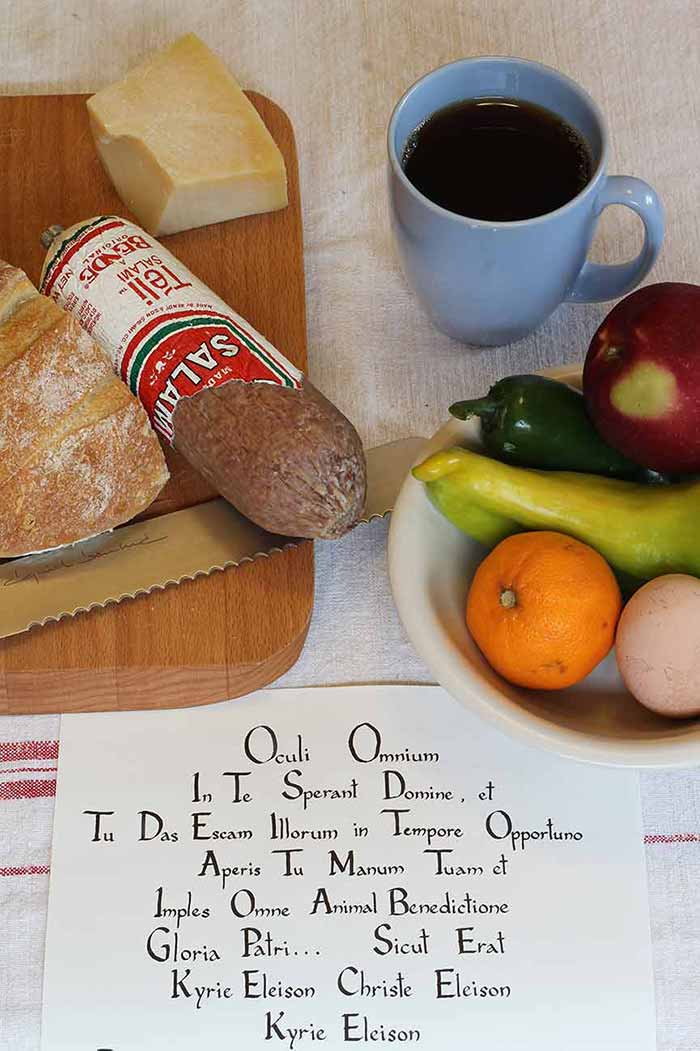

On the other hand, many of the texts are repeated only annually, even less often for those particular to special occasions. One might spend a lifetime without seeing the consecration of an altar stone, for example. There is therefore plenty of fresh material to keep things challenging. And some of it is pretty challenging! The Office Hymns, for example, can be as grammatically acrobatic as Horace, and presume a broad vocabulary, some of it post-classical. The range of texts and styles in the Latin liturgy can hardly be exaggerated. The Canon[14] is reminiscent of the highly stylized pagan prayers that predate Christianity.[15] The biblical readings are early Latin translations of more than a millennium’s worth of Greek and Hebrew scriptures. Readings from the church fathers are often in a late classical style. The Regula Monachorum is somewhere between classical and vulgate. The hymns of the Divine Office were composed in an evolving style between the 300s and 1200s, before being severely revised in 1632 under Urban VIII to make them more Augustan. The subject matter is as variable as the style, ranging from prayer in the strict sense to instructions for receiving guests in a monastery, with healthy doses of historical narrative, theology, and of course exposition of the central dogmas of the faith.

Speak up!

One cannot learn a language without attention to its heard and spoken aspects. It is much more tempting to dump these in favour of silent reading when the language one is learning is not used in daily conversation. You can’t turn on the Latin radio station on the way to work (apologies to Nuntii Latini) or swing by the Latian quarter for an espresso and a box of mussels with garum. Latin prayer, on the other hand, is usually spoken aloud. You can’t escape from your ineptly rolled ‘r’, and it’s harder to ignore vowel quantity. When you’re not speaking yourself, you’re listening to other people speaking, and learning from their superior diction. It’s even edifying to hear the occasional priest who clearly has no Latin at all, whose mistakes can silhouette the right habits you weren’t explicitly aware of before.

Check your work

Most popular editions of Latin prayer books come with a parallel vernacular text. Mr. Bailey has explained the utility of a crib elsewhere, so I needn’t dwell on it here. Still, I’ll add one unexpected advantage of the English cribs: They are generally very loose, since they’re intended to read pleasantly in English. That means they’re mostly useful for the occasional word one doesn’t know, and the reader is not tempted to let the crib do all the translating.

Two drawbacks

There is one way the Latin habit of prayer falls short of true linguistic immersion: One never improvises these prayers, but relies on those found in the tradition. So although you’re speaking Latin, you’re not forced to make the jump from concepts to sentences. A corollary: written Latin is not part of this regimen at all. If you want to become truly fluent in Latin, you will need to supplement your prayer life with colloquial immersion, such as that offered by Vivarium Novumand SALVI. Receptive language, on the other hand, reading and hearing, does not suffer from this drawback, and can be learned very well in the liturgy.

If I’ve sparked any interest in these few paragraphs, I will also have caused a small problem. The Latin liturgy can be devilishly hard to find! When the vernacular Mass was permitted by Pope Paul VI, Latin went the way of many of the Church’s other priceless treasures, whether musical, artistic or architectural: Technically still allowed, but systematically uprooted throughout most of the world. For a while, Catholics who preferred the Latin forms were looked on with a degree of suspicion usually reserved for schismatics. (We still enjoy feeling a bit countercultural. I’m sure this is common ground with non-Catholic Latinists!) In any case, recent years have seen a slow but steady return of Latin, and while coverage is still thin, at least it’s broad, as you can see from this map. And there’s no geographical impediment to picking up a Breviary [16] and saying the psalms in Latin at home.

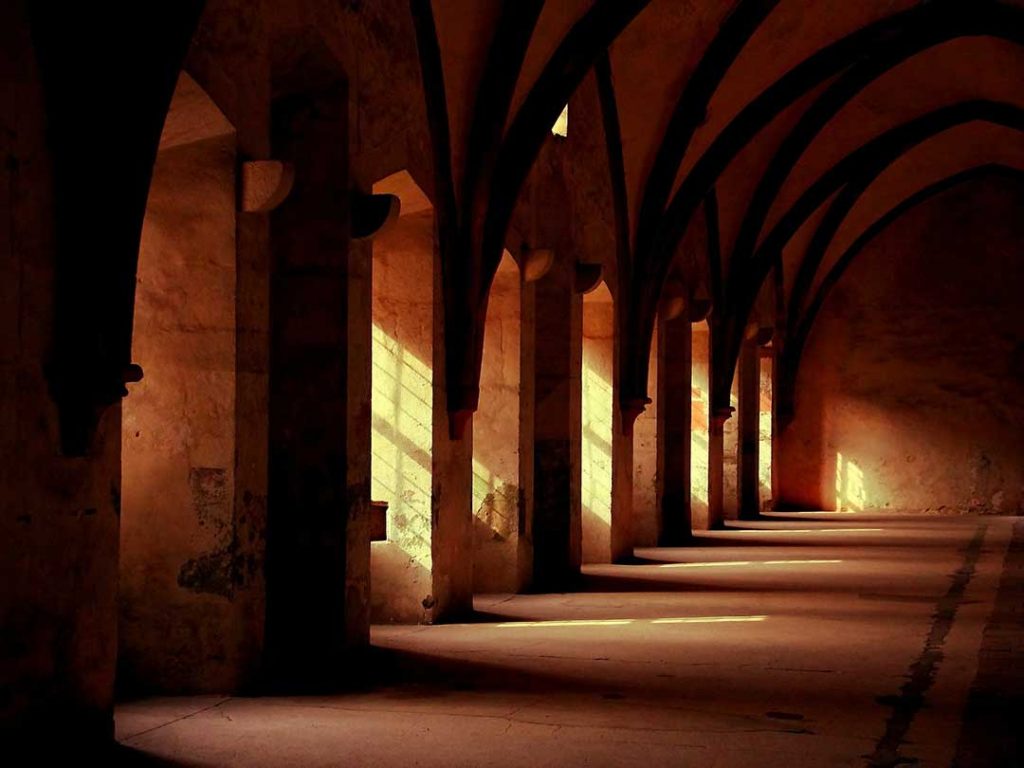

The Cadillac Latin Experience

But if you really want to know Latin prayer, there’s no alternative to visiting a traditional monastery. The flag ship is Fontgombault in France, with 100 monks, but there are similar houses in England, Scotland, Ireland, Italy and Wyoming, to name only a few. Here you will see Latin living in the bloom of her youth, and forget that anyone ever dared to call her dead. The monks saved and recast Western civilization in Latin over centuries, and clearly intend to do the same for centuries to come. But be very careful: Clear Creek Abbey in Oklahoma was founded by American visitors to Fontgombault. They only wanted to see Western civilization at its roots. Instead, they chose to pray in Latin for the rest of their lives.

Valete.

References

[1] Buckley TA. Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent. Library of Alexandria; 2016 Nov 24. Available here.

[2] XXIII J. Apostolic Constitution Veterum sapientia (February 22, 1962). AAS. 1988 Dec 4;54:129–35.

[3] Sacrosanctum Concilium, para. 36

[4] Pope Paul VI, Sacrificium Laudis, August 15, 1966

[5] Pope John Paul II, Dominicae Cenae, February 24, 1980, sec. 10

[6] Pope Benedict XVI, Motu Proprio: “Summorum Pontificum”

[7]Pope to Pontifical Academies: Transmit Latin Culture to Youth

[8] The public prayer of the Church, including originally public prayers when said privately.

[9] Thou shalt sprinkle me, O Lord, with hyssop and I shall be cleansed.

Thou shalt wash me, and I shall be whitened more than snow.

[10] I shall enter unto the altar of God.

[11] Let my prayer, O Lord, be directed as incense in Thy sight: the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice.

[12] The poor shall eat, and be filled.

[13] O Jesus, hope of the penitent, how gracious you are to those who ask, how good to those who seek you, but what to those who find you?

[14] The central prayer of the Mass, containing the Consecration. It has remained essentially unchanged from at least the 500s until the present day, though several fabricated new options were introduced after Vatican II. In practice, these are not used when the Mass is in Latin.

[15] Christine Mohrmann, Liturgical notes

[16] The compact manual of most of the daily hours of prayer