In the Roman playwright Terence’s play Adelphoe, written c:a 160 B.C., two of the characters, Syrus and Ctesipho, are speaking when Syrus blurts out:

— Em tibi autem!

— Quidnamst?

— Lupus in fabula.

— Pater est?

— Ipsust.

— Terence, Adelphoe 535–539i.e.

— But look!

— What is it?

— Talk of the devil!

— It’s my father?

— In person.

(Transl. Barsby, 2001)

Terence makes it rather clear to us in just these few lines what the proverb Lupus in fabula, i.e. literally “The wolf in the story”, means and provides clues as to how to use it:

When you speak of someone or something and they or it suddenly appears, almost as if you were calling or summoning them, this proverb is perfect.

An English equivalent would be to Speak, or talk, of the Devil, and you use the Latin version in just the same way.

Varro The Wolf

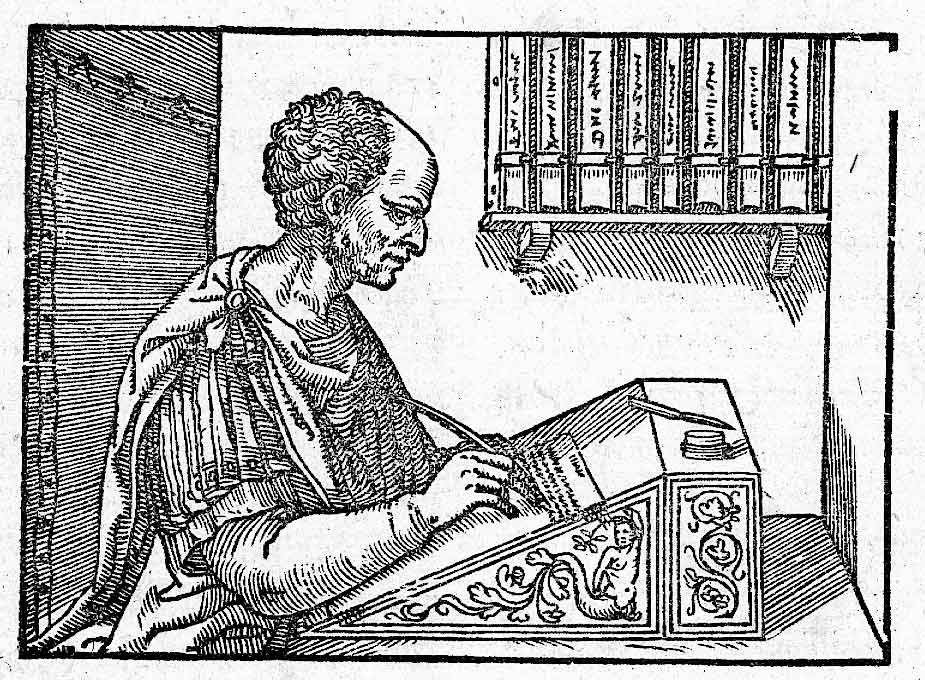

However, we not only find Lupus in fabula in Terence’s, but also in the Roman orator and statesman Cicero’s work. In a letter to Atticus written in Tusculum the 9th of July 45 B.C., Cicero tells Atticus about Varro, who had swung by Cicero’s house:

“De Varrone loquebamur: lupus in fabula, venit enim ad me et quidem id temporis ut retinendus esset.”

— Cicero, Att. 13.33a.1i.e. ”We were speaking of Varro: Talk of the devil! He called (i.e. visited), and at such an hour that I had to ask him to stay.” (transl. Shackleton Bailey, 1999)

As mentioned, in English you can say speak of the Devil or talk of the Devil. Two versions of one proverb, that ultimately mean the same thing. For Latin, it is the same.

Wolf Version

While Cicero and Terence used Lupus in fabula, “the wolf in the story”, Plautus (c:a 254–184 B.C.) had his own version. In his play Stichus the character Epignomus says to Pampila, just as Gelasimus enters the stage:

“Atque eccum tibi lupum in sermone”

— Plautus, Stichus, 577i.e. “And look, here you have the wolf in the fable (lit. “in the conversation”).” (transl. Melo, 2013)

Dogs, Donkeys And Devils

This proverb, to speak of someone as a way of summoning them or perhaps as a warning of keeping your tongue, is found in different versions all around the world. Some speak of dogs, cats or wolves, other proverbs of donkeys, devils or tigers, and yet others of kings, lions and trolls.

Usually the proverbs are split in two with only the first half used, such as with the English versions (there are several):

- Speak of the devil (and he is at your tail)

- Speak of the devil (and he shall appear)

- Speak of the devil and he’s presently at your elbow, etc.

The French do the same but derive their proverb from the Latin with their Quand on parle du loup, (on en voit sa queue), i.e. “When one speaks of the wolf, (one sees its tail).”

The Swedes are a bit more superstitious and instead uses trolls: När man talar om trollen, så står de i farstun, i.e. ”When you speak of the trolls, they’re in your hallway.” The second half is rarely used.

The Danish and Norweigians are perhaps the most optimistic as they say: Når man taler om solen, så skinner den/Når man snakker om sola, så skinner’n, which translates to “When you speak of the sun, it shines.”

Lupus In Fabula In Other Languages?

Dansk: Når man taler om solen, så skinner den.

Deutsch: Wenn man vom Teufel spricht, kommt er gegangen.

Español: Hablando del rey de Roma, por la puerta asoma!

Français: Quand on parle du loup, (on en voit sa queue).

Italiano: Lupo in favola.

Norsk: Når man snakker om sola, så skinner’n.

Svenska: När man talar om trollen (så står de i farstun).

Português: Falando no diabo, aparece o rabo.

References

- Terence. Phormio. The Mother-in-Law. The Brothers.Edited and translated by John Barsby. Loeb Classical Library 23. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Cicero. Letters to Atticus, Volume IV. Edited and translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Loeb Classical Library 491. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Plautus. Stichus. Trinummus. Truculentus. Tale of a Travelling Bag. Fragments. Edited and translated by Wolfgang de Melo. Loeb Classical Library 328. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013.

If you like proverbs with wolves, you can learn more about what holding a wolf by the ears mean in Latin here.

If you want to help out, consider supporting Latinitium on Patreon by clicking below.