Daniel’s library

Here you’ll find my favourite Latin-related books, everything from critical editions, books on stylistics, to comics.

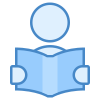

Olaus Magnus, Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus

Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus was a best-seller in the 16th century across Europe, even though it treats only Scandinavia. I love this book because each chapter is self-containing, so you can pick a random chapter and read two pages without continuing.

The subject matter is immense: you can read about fishing and hunting, or the gods of Norse mythology, or about snowball fighting rules in Scandinavia.

Last summer, in a small town, I bought this beautiful facsimile of the original first edition from 1555. They had five Latin books, and this book was among them!

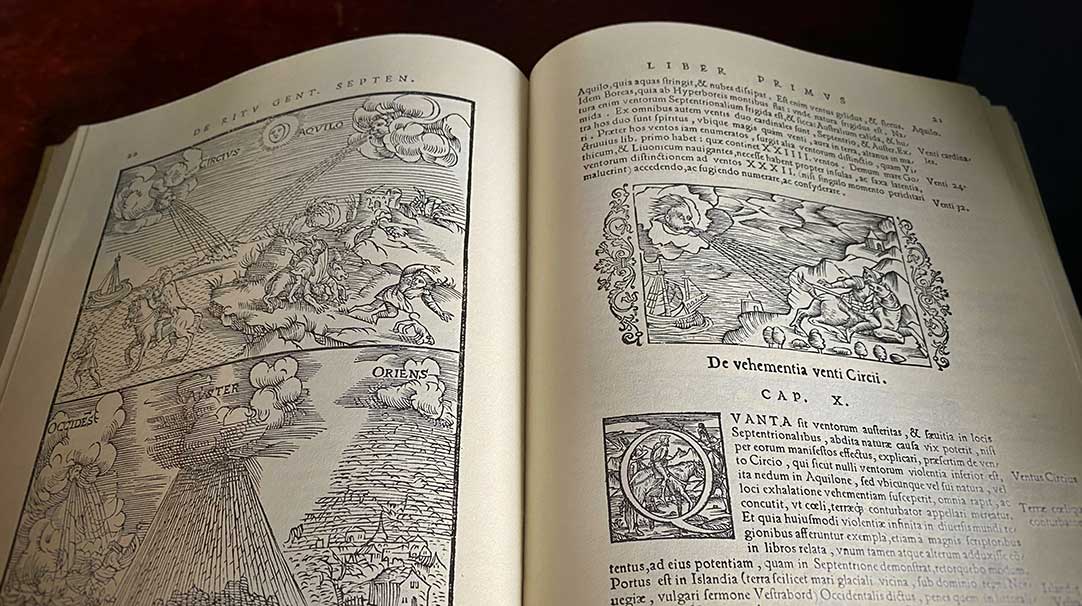

Ovid, Heroides

Heroides are versified letters that Ovid imagines written by famous women of antiquity, e.g., Penelope writes to Ulysses. My favorite one is the one Ariadne writes to Theseus after being deserted by him on the island of Naxos. It always moves me almost to tears.

I found this beautifully bound edition in used books store in Nice, France, a few years ago. It is a bilingual Latin-French edition, which allows me to practice my French while reading Ovid.

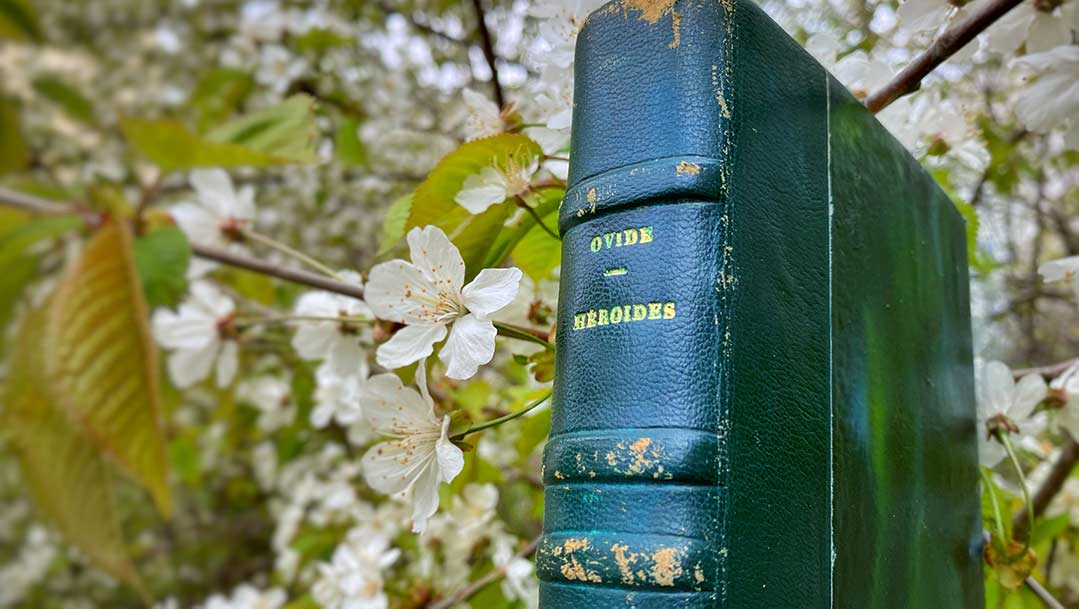

H.C. Nutting, Ad Alpes

It’s no secret that we re-published Ad Alpes in 2016 and thus largely resurrecting it. Nevertheless, I read (or rather) listen to it almost daily. I am amazed by how Nutting has so elegantly woven together passages from many Roman authors into his own narrative.

Before we published a new edition, it was an extremely rare book, which my students complained about when I told them to get it. Only three were able to find it. The photo above shows our new edition of Ad Alpes.

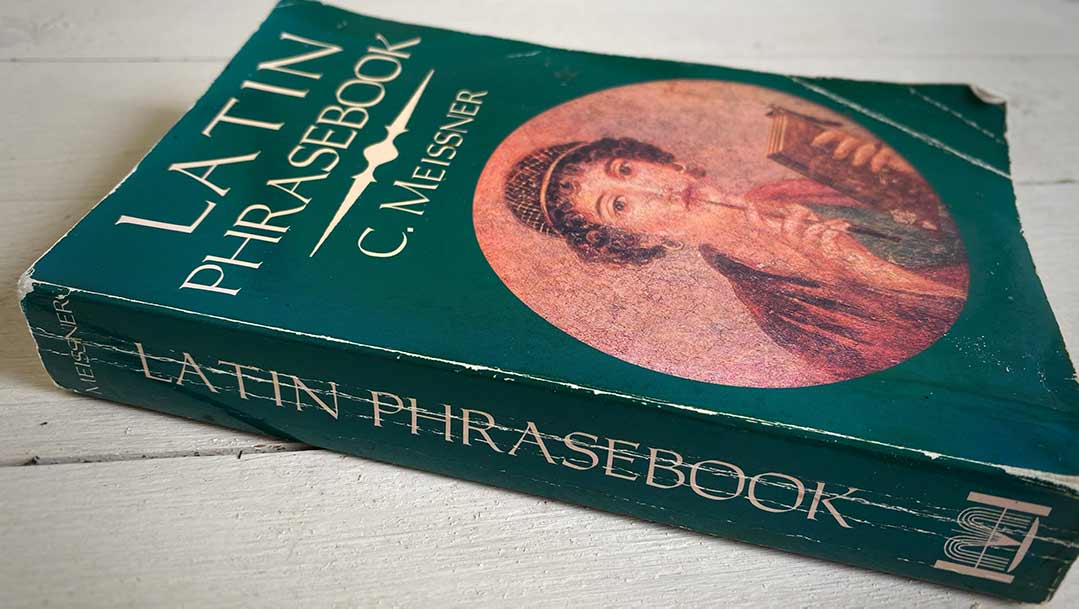

C. Meissner, Latin Phrase Book

I remember the day this book arrived in the mail: I was so excited to have a treasure trove of attested Latin expressions to memorize like a checklist.

Countless of the expressions I learned those first few weeks are still etched into my mind, and I use them every day when I speak Latin.

Sometimes, when I come across the source of the expression, I feel this strange sense of déjavu—I know the expression but haven’t read the passage whence it’s sourced before!

You can get the Latin-English version here.

Burkhard & Shauer, Lehrbuch der lateinischen Syntax und Semantik

This is the new version of Menge’s classic Repetitorium der Lateinischen Syntax und Stilistik. It (and the original) is a large part of why I decided to learn German. This book is for those who want to learn the finer points of classical Latin style and usage. I know many prefer Menge’s original, but I think the layout of this edition makes it much more suitable for a quick consultation. I usually compare with Menge’s original to see if there are any great differences.

I just love to read this book: open a random page and just discover new things every time.

You can get this enormous book here.

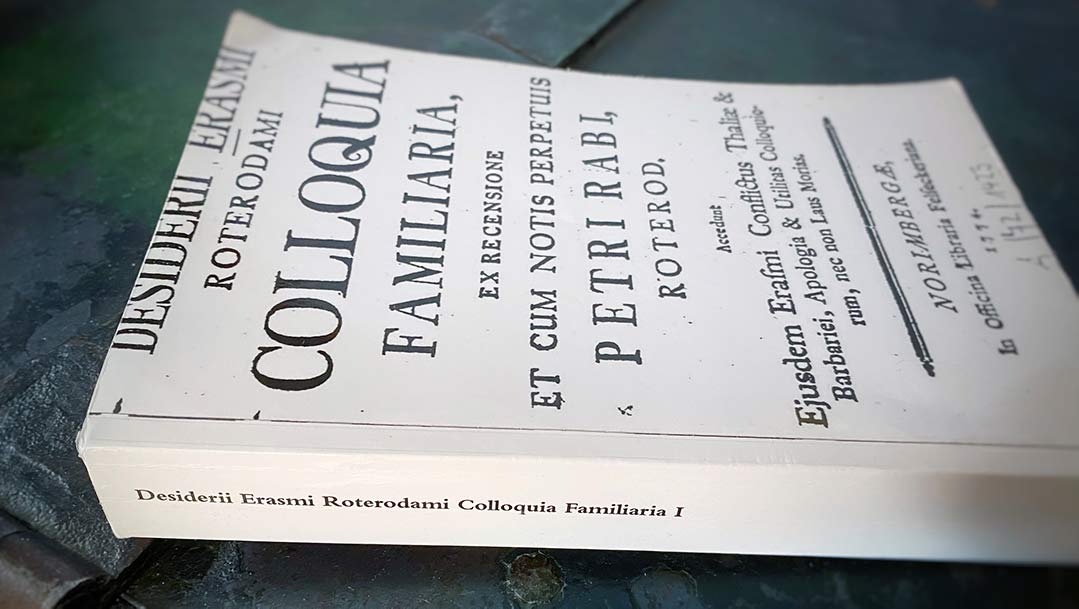

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Colloquia Familiaria

My scholarly research focuses on the Latin school dialogues of the 16th century; this has allowed me the pleasure of reading through the entire genre with thousands of dialogues. Among these, Erasmus’ dialogues are the most fun, by far.

These are dialogues but largely very advanced in their syntax and lexicon. They are not so much school dialogues, as they are satirical dialogues in the spirit of Lucian’s dialogues.

Erasmus discusses and mocks contemporary ideas and institutions, which earned the book a place on the Vatican’s Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

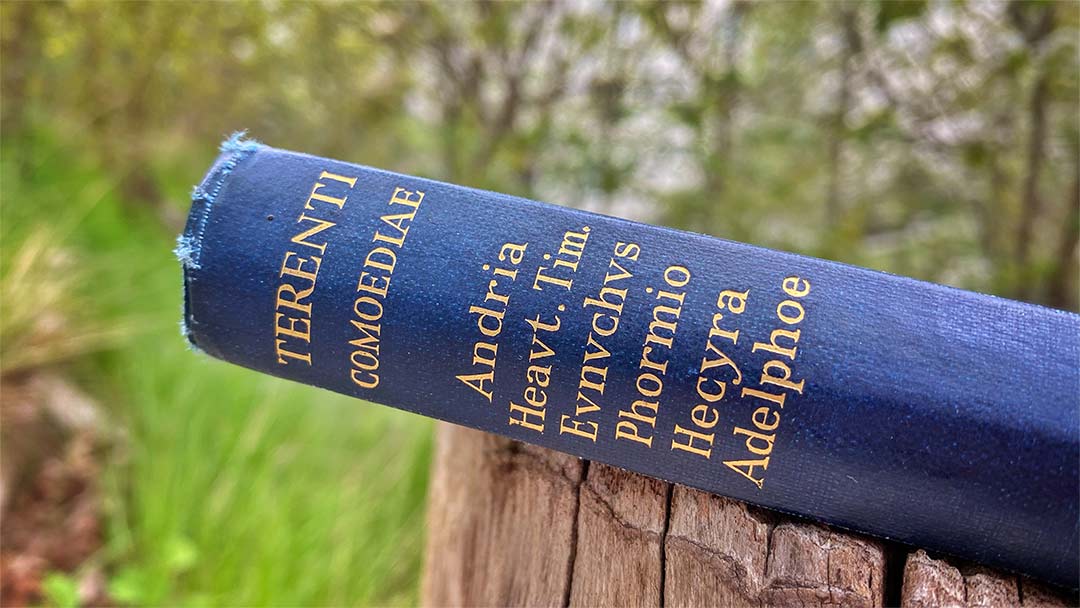

P. Terenti Afri: Comoediae

Robert Kauer and W. M. Lindsay (eds).

You can rarely get an author’s complete works in small volume, but with Terence, alas, that is possible: he only wrote six comedies.

I found this edition from Oxford Classical Texts in a used books store in Uppsala, Sweden, ten years ago and instantly bought it.

I’ve read and re-read these six comedies countless times and internalized much of the vocabulary and phraseology of Terence. They’re fun and give an insight into the mid of the Roman people and their sense of humor.

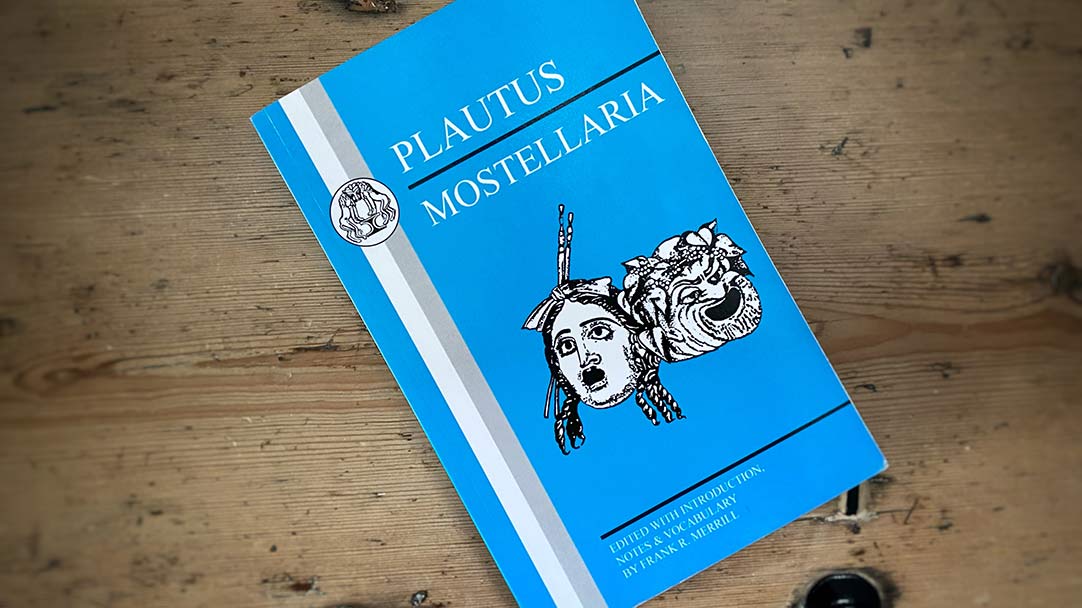

Plautus: Mostellaria, Frank R. Merrill (ed.)

When I want to have a laugh while still reading Latin, Plautus is my go-to author. His comedies are replete with silly, unpolished humor, which stands in stark contrast to the common idea of Roman literature as serious and all but cut from white marble. Mostellaria is just one of many of my favorite Plautus plays, but it makes me laugh every time: The way Plautus creates silly characters mortified by a haunted house is just priceless. Well worth a dozen readings.

I got this edition for a course I was teaching several years ago and really liked the commentary: Plautus must be read with a good commentary; otherwise, you’ll miss so many nuances and obscure elegancies :).

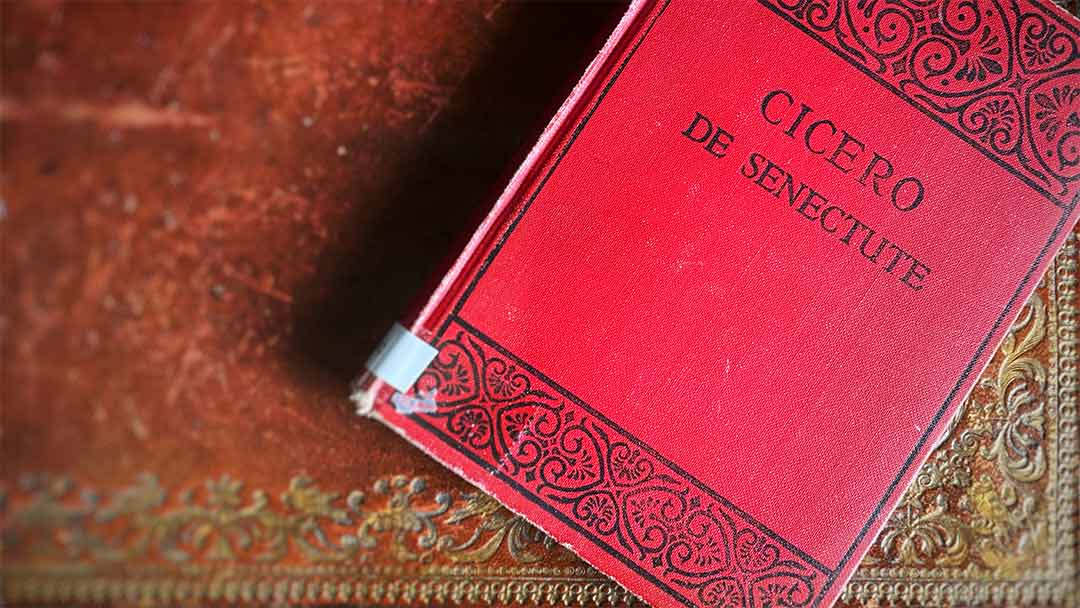

Cicero, De Senectute (ed. Huxley)

I got this edition many years ago from my first Latin teacher, Professor Hans Aili. It’s a classic school edition and thus tiny and portable.

This is my favorite work by Cicero: he wrote it as a consolation to himself in old age, but it’s not a treatise. Instead, he creates a fictitious dialogue where he has Cato the Elder talking about the nature of old age, the burdens, the pleasures, and how to cope with it.

While Cicero’s orations are tied to contemporary events, De Senectute is timeless. It always gets me thinking about the passing of time and how we think about growing old.

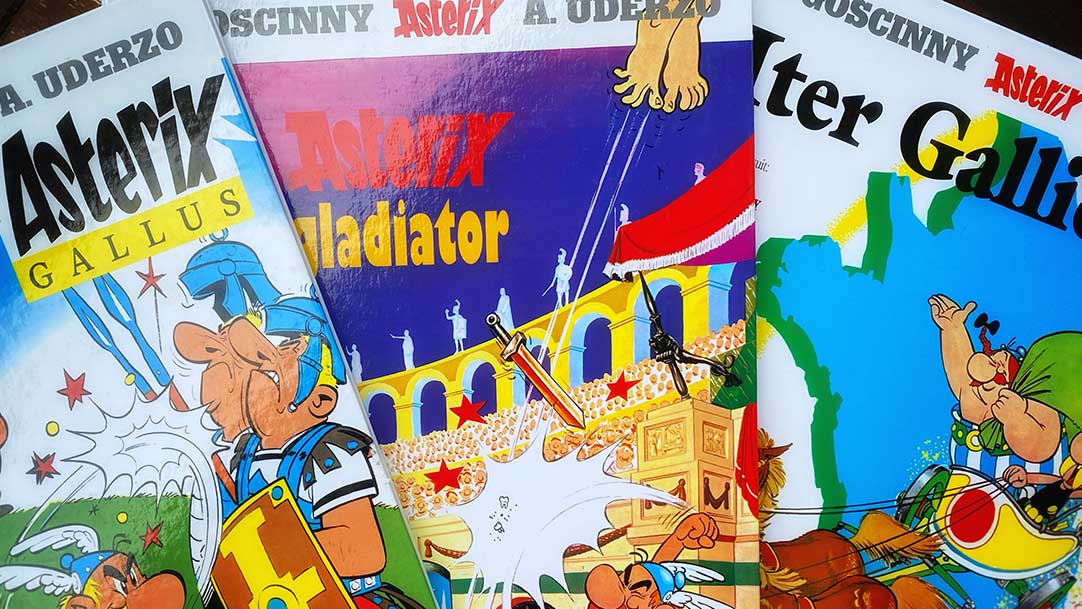

Astérix et Obélix (in Latin)

I have been a dedicated fan of Astérix and Obélix—especially Obélix—since I was a young boy. The amount of erudite references that I discover every time I read them always makes me laugh.

The Latin translations are fun, quirky and very suitable for the subject. The Latin itself does not strive to be hyper classical, but instead is rather eclectic and charming.